There are many offences which are unable to be finalised in the Local Court, and must be referred (or ‘committed’) to a higher court such as the District or Supreme Court for determination. These are known as ‘strictly indictable’ cases.

Many other offences call for either the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (or ‘DPP’) or defence to decide whether they will be committed to a higher court. These are known as Table 1 indictable offences.

There are other offences where only the DPP can decide whether to commit to a higher court. These are called Table 2 indictable offences.

If your case is committed to a higher court and you continue to plead not guilty, it will ultimately proceed to a trial before a jury or a judge-alone; unless, of course, your lawyer is able to persuade the DPP to withdraw the charges.

District and Supreme Court trials should be handled by specialist criminal defence lawyers who are vastly experienced in these types of cases.

The defence team at Sydney Criminal Lawyers has an unparalleled track record of winning trials in difficult circumstances, including where clients were advised by other law firms to plead guilty – from Australia’s largest ever heroin importation trial, to many highly-publicised sexual assault trials, to several notable murder trials.

If you or a loved-one are facing the prospects of a District or Supreme Court trial, call us today on (02) 9261 8881 to arrange a conference with one of our experienced defence lawyers, and see why we are Australia’s Most Awarded Criminal Law Firm.

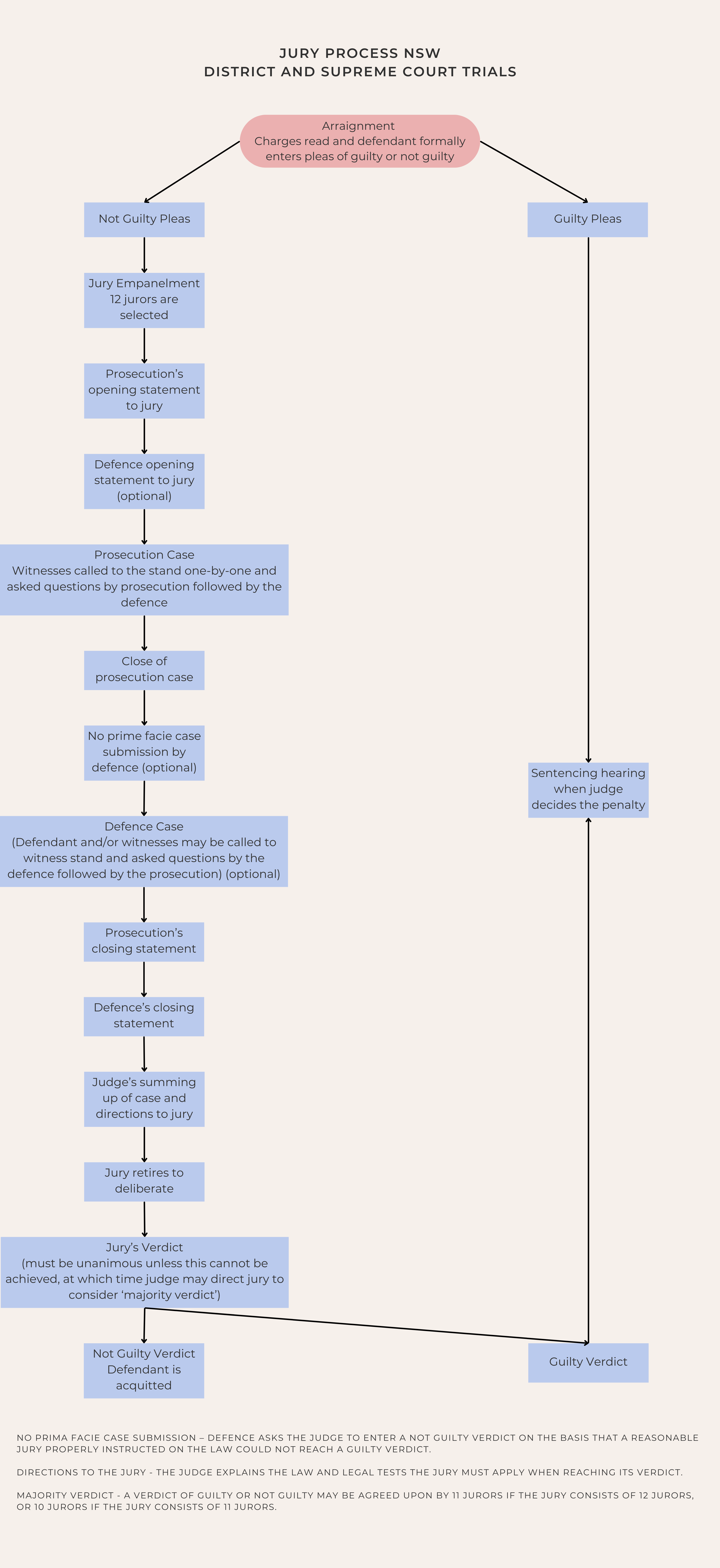

Here is a basic guide to the main steps in a District or Supreme Court trial.

Arraignment

The first step is called ‘arraignment’.

This is where the Judge’s Associate (who is the person sitting in front of the judge) reads aloud to the Accused (who is the person on trial) each count on the indictment (ie each charge). After each count is read, the Judge’s Associate will ask the Accused: ‘how do you plead, guilty or not guilty’.

The Accused will then say either ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty’.

During the ‘arraignment’, there will be a large number of people in the public area of the Courtroom.

These are prospective jurors ie the group from which the jury panel will be chosen.

Note: if you are to be arraigned, stand when your name is called and remain standing until you have entered pleas to all the charges.

Try to remain calm and composed, and stay focused on the Judge’s Associate throughout the process.

Jury empanelment

The next stage is to select (or ‘empanel’) a jury. This is done in the following way:

- The Judge’s Associate will pick numbers from a box; a bit like a lottery. Each prospective juror will have a numbered ticket, and if their number is picked they will take a seat in the ‘jury box’. Each person will take a bible (unless they wish to give an ‘affirmation’ rather than swear an ‘oath’). 12 people will initially be picked in this way; then

- The Judge’s Associate will ask each potential juror to stand up and swear an ‘oath’ (on the bible) or an ‘affirmation’ (if they don’t wish to swear on the bible). As each juror stands up, the Prosecutor or Defence lawyer can have that juror removed from the jury by saying: ‘challenge’ followed by the name of their client eg ‘challenge Mr Brown’. The Prosecution represents the ‘Crown’, so the Prosecutor will say ‘challenge Crown’. Each Accused will have 3 ‘challenges’, and the Prosecutor will have 3 challenges for every Accused person. So, if you and two others are on trial at the same time, you will have 3 challenges, each of the two other Accused will have 3 challenges (so 9 challenges altogether for the 3 Accused), and the Prosecution will have 9 challenges.

- When a potential juror is ‘challenged’, he or she will leave the jury box. Another ‘lottery’ will take place to fill the seats of those who are challenged. The replacements can also be challenged, until finally 12 unchallenged people are left. These remaining 12 form the ‘jury panel’.

Prosecution opening

The Judge will then invite the Prosecutor to give a general outline of what is being alleged against the Accused.

No witnesses are called at this stage and no documents are ‘tendered’ (ie handed up to the Judge as evidence).

Defence opening (optional)

The Judge will then ask the criminal defence lawyer if he or she would like to outline the defence case.

The criminal defence lawyer will usually only give an extremely general opening or no opening at all, so that it doesn’t tie the defence down to a specific version of events.

It is often better for the criminal defence lawyer to hear the whole Prosecution case (ie to wait until all of the Prosecution witnesses have given their evidence) before deciding whether or not to give an ‘opening address’.

Prosecution case

The Prosecution witnesses are then called to the witness stand one at a time.

They may include police officers, civilian witnesses (eg people who saw or heard the events), customs officers (in drug importation cases), expert witnesses (eg DNA experts, psychiatrists, other doctors) etc.

(i) Examination in chief

After being ‘sworn in’, each Prosecution witness will first be questioned by the Prosecutor.

There are many rules of evidence that criminal defence lawyers must follow when asking questions.

One of the rules is that when questioning your own witness, you cannot usually ask ‘leading questions’, which are questions that contain or suggest a particular answer.

The following are examples of ‘leading questions’:

- ‘you went to Drinkalot Pub at around 8pm on 27th December didn’t you?’.

This question suggests that the witness answer as follows: ‘I went to Drinkalot Pub at….. etc’. Similarly,

- ‘did you then see the Accused pointing a gun at the teller?’

Again, this suggests the answer: ‘I saw the accused pointing a gun at the teller’. In contrast, the following questions are not leading, as they do not contain or suggest a particular answer:

- ‘when and where did you go then?’; and

- ‘did you see the Accused do anything after that?’.

(ii) Cross-examination

After the Prosecutor has finished questioning a witness, the criminal defence lawyer will have the opportunity to ‘cross-examine’ (ask questions to) that witness.

Leading questions are allowed at this stage.

‘Cross examination’ gives the criminal defence lawyer a chance to reveal any inconsistencies or untruths in the witness’s evidence.

It also allows the defence lawyer to ‘put its case’ ie to suggest what the Accused’s defence will be.

For example, the criminal defence lawyer may ‘put its case’ to a Prosecution witness as follows:

- ‘I put it to you that it wasn’t my client Mr Smith that you saw point the gun at the teller, but actually another person Mr Jones. What do you say about that?’

The criminal defence lawyer must ‘put its case’ at some stage during the trial if it wants to rely on those facts as a defence to the charges.

In other words, if a Prosecution witness says during ‘examination in chief’ that Mr Smith was holding a gun but the criminal defence lawyer fails to suggest at any time that Mr Smith was not doing so, the defence lawyer cannot say during its closing address that Mr Smith is innocent because he was not holding a gun (this rule is often referred to as the ‘Rule in Brown v Dunn’).

It is therefore very important that your criminal defence lawyer ‘put its case’ at some stage.

(iii) Re-examination

If new facts or issues are raised during ‘cross examination’, the opposing party can ask questions (in other words ‘re-examine’) about those facts or issues only.

New facts or issues are those that did not arise during the ‘examination in chief’ of the particular witness.

For example, if during examination in chief Ms Pearly does not say anything about the fact that she saw Mr Bloggs holding a gun, but she says this when ‘cross examined’ by the criminal defence lawyer, the Prosecutor may ‘re examine’ her (ie ask her questions) only about the issue of who she saw holding the gun.

Close of Prosecution Case

After the questioning has finished, the Prosecution will declare its case against the Accused ‘closed’ (ie concluded).

No case submission by Defence (optional)

If the criminal defence lawyer thinks that the Prosecution case was particularly weak, we can ask the Judge at this stage to ‘direct an acquittal’; in other words, to tell the jury that it must find the Accused ‘not guilty’.

The Judge will only do this if he or she concludes that the Prosecution has failed to produce enough evidence for any ‘reasonable jury’ to find the Accused ‘guilty’.

If the Judge ‘directs an acquittal’, the Accused is ‘not guilty’ and the case will be dismissed.

Defence opening (optional)

The Judge will then ask, once again, whether the criminal defence lawyer would like to outline his or her case.

By this stage of the trial, the defence lawyer will know exactly what the Prosecution is alleging.

The criminal defence lawyer will also have obtained detailed ‘instructions’ (ie information) from the Accused, and will have formulated a defensive strategy.

Defence case

Sydney Criminal Lawyers® will then decide which, if any, of their witnesses will be called to the witness stand.

The Accused (optional)

The Accused does not have to give evidence as a witness.

In fact, one of the most difficult decisions Sydney Criminal Lawyers® must make is whether to call the Accused to the witness stand.

In making that decision, the criminal defence lawyer will consider a number of things, including:

- the likely strength of the Accused’s evidence. If we feel that the information received from the Accused during conference is likely to substantially benefit the defence, they will of course be more likely to advise the Accused to give evidence.

- the strength of the Prosecution case. If the Prosecution case is very strong, we will be more likely to advise the Accused that refuting evidence is required. On the other hand, if the Prosecution case is very weak, we may feel that it is unacceptably risky to expose the Accused to ‘cross examination’.

- the likely ability of the Accused to withstand ‘cross examination’. Giving evidence as a witness is extremely stressful, especially as an Accused facing the possibility of a lengthy prison sentence. Because some people handle great pressure better than others, the criminal defence lawyers may try to predict or test the likely ability of the Accused to be composed and convincing under ‘cross examination’. Sydney Criminal Lawyers® do this using experience and/or by asking ‘cross examination’ style questions in conference. Sydney Criminal Lawyers® are, of course, more likely to advise a confident, composed and convincing Accused to give evidence than one who is extremely nervous and uncertain of their answers.

If the Accused chooses to give evidence, he or she will face the same procedure as any other witness: examination in chief (by the criminal defence lawyer), then cross examination (by the Prosecutor), and finally re examination (by the criminal defence lawyer, but only if new facts or issues were raised during cross examination).

Other witnesses (optional)

The remaining Defence witnesses will then be called to the witness stand one at a time, and questioned following the same procedure: examination in chief (by Defence), cross examination (by Prosecutor), then re examination (by Defence).

Prosecution closing statement

After the Defence witnesses have finished, the Prosecution will give its ‘closing statement’ to the jury.

That ‘statement’ may involve the Prosecutor outlining the ‘elements of the offence’; in other words, the ‘ingredients’ that must be proved by the Prosecution for the Accused to be found ‘guilty’.

For example, the ‘elements of the offence’ of ‘robbery’ are as follows:

- that the Accused intended to steal property; and

- that he or she did in fact take property;

- from a victim;

- using violence or by putting the victim in fear.

Note: – the Prosecution must prove each and every one of the ‘elements’ beyond reasonable doubt.

The Prosecutor will then try to convince the jury that the evidence in the trial proves the guilt of the Accused ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. To illustrate, the Prosecutor may say something like:

‘You heard the evidence of Mr X (a prosecution witness) that it was Mr Smith (the Accused) pointing his gun and threatening Ms Fragile (the bank teller).

You also heard the evidence of Ms Fragile that she was extremely scared and handed the cash to Mr Smith, who then left the bank holding the bag of cash. Considering that evidence, you the jury are entitled to find that Mr Smith intended to steal money, that he did in fact steal money, that there was at least one victim – whether that victim is Ms Fragile, others in the bank and/or or the bank itself – and that Ms Fragile and others were very frightened for their safety.

That being so, the elements of robbery are satisfied – and satisfied ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ – and you are therefore entitled to return a verdict of ‘guilty’…’ etc etc.

Criminal defence closing

- After the Prosecutor has finished, the criminal defence lawyer will be invited to give its ‘closing statement’. Sydney Criminal Lawyers®’ job is to raise ‘reasonable doubt’ in the jury’s mind about the Accused’s guilt; in other words, to convince the jury that the Accused may not have committed the crime. We may do this by:

- pointing out weaknesses in the Prosecution case, eg inconsistencies or deficiencies in the evidence of Prosecution witnesses;

- pointing out strengths in its own case, eg credible evidence given by the Accused and/or by other Defence witnesses;

- offering alternative explanations for the events, eg the possibility that someone else committed the offence; and so on.

- To illustrate, the criminal defence lawyer may say something like:

‘You heard my client’s evidence (ie the Accused’s evidence) that he was at home at the time of the bank robbery.

He did not have to give evidence; in fact, an Accused person is quite entitled not to take the witness stand at all.

However, he chose to take the stand and, therefore, to be cross examined by the Prosecutor.

His evidence is supported by the evidence of his wife, Ms Smith, who you will recall took the witness stand and confirmed that her husband was definitely at home at the time of this offence….. etc etc. You will also recall the uncertainties in Ms Fragile’s evidence who – having experienced an extremely traumatic confrontation – was understandably unsure of several things, including…… (examples)…

In those circumstances, you will be well-justified in having a reasonable doubt in your minds about whether my client was at the bank at all; in fact, one might think that you should, considering all of the evidence, have such a doubt; especially because my client was, in fact, not at the bank on the day in question.. etc etc…

Where there is any such reasonable doubt, you must find my client ‘not guilty’… etc’.

Judge’s ‘summing-up’ to jury

The next stage is the judge’s ‘summing up’, which is where the judge summarises the issues, arguments and evidence in the case.

In the ‘summing up’, the judge might say what he or she thinks the case boils-down to, summarise the lawyers’ central arguments, and outline the main points of each significant witness’s evidence.

Judge’s ‘directions’ to jury

The Judge will then explain the relevant laws and how they relate to the case at hand. This is called ‘giving directions’. For example, the Judge might direct as follows:

‘If you do not have a ‘reasonable doubt’ that the Accused pointed the gun at Ms Fragile (the bank teller) and took the money using such violence, then you must find him ‘guilty’.

You must also return a verdict of ‘guilty’ if you find ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ that, although the Accused didn’t hold the gun or take the money himself, he was present and involved in the crime in another capacity.

It wouldn’t matter if he acted as ‘crowd controller’, ‘lookout’, ‘getaway-driver’ or otherwise; if he was there and involved, then you must find him ‘guilty’ of the crime.

This is because the law would consider him part of the ‘joint criminal enterprise’ that committed the offence.

If, on the other hand, you have a ‘reasonable doubt’ that the Accused was present at the bank or that he was, in fact, involved in the offence, then you must find him ‘not guilty’.

You must also return a ‘not guilty’ verdict if you have a ‘reasonable doubt’ about any of the other ‘elements’ or ‘ingredients’ of the offence; such as whether the Accused in fact intended to steal. You can only return a ‘guilty’ verdict if the Prosecution has proved each and every one of the elements ‘beyond reasonable doubt’……. etc etc’.

Jury deliberations

After the Judge has finished, the jury will be asked to retire to consider its ‘verdict’; in other words, to decide whether the Accused is ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty.

In any jury trial, the Judge is the judge of the law and the jury is the judge of the facts.

This means that although it must accept the Judge’s ‘directions’ about the law, the jury is ultimately responsible for determining the ‘verdict’, and it will do this based on what it judges to be the facts.

For example, if there is conflicting evidence about whether or not the Accused was at the bank at the time of the offence, the jury (not the Judge) must determine the issue.

Until recently, the law in NSW was that jury verdicts had to be unanimous; meaning that all 12 jurors had to agree that the Accused is either ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty’. Recently, the law has changed to allow ‘majority verdicts’ whereby all except one juror can agree on a verdict (eg 11 guilty and 1 not guilty = guilty verdict).

It is expected that the jury will consider all of the evidence before reaching a verdict.

However, because jury deliberations are secret, no-one except for the jurors will know exactly how the verdict was reached.

Jury questions

If any of the jurors have questions about the evidence, the jury foreperson can pass a note containing the questions to the Court Officer, who will in turn pass that note to the Judge.

The Court will then ‘re-convene’ (ie the lawyers, Court Officials and Accused will be called back to the Courtroom) and the questions will be read aloud by the Judge, usually in the absence of the jury.

The Judge and criminal lawyers will then discuss whether the questions will be answered and, if so, how they will be answered.

The jury will then be brought back into the Courtroom and advised of any answers.

Note:- the jury can ask questions in this way at any stage of the trial.

Verdict

When a verdict is reached, the Court (including the jury) will re-convene.

The jury foreperson will then stand up, after which the Judge’s Associate will read the charges one at a time, asking the foreperson each time: ‘how do you find the Accused, ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty’’.

The foreperson will then give the verdict, after which the Judge’s Associate will say: ‘so says your foreperson, so say you all’.

After all of the verdicts are given, the Judge will thank and discharge the jury.

Sentencing

If the Accused is found ‘guilty’, the matter will be set-down for sentencing.

If a ‘Full Pre-Sentence Report’ is ordered by the Judge, the sentencing will normally be held in 6-8 weeks.

If not, and no other reports are required (eg medical or psychological reports), the sentencing can occur at any time; even on the day of the verdict (if that is suitable to the Judge and both sides).

On the day of sentencing, any character references and medical reports will be handed-up to the Judge, and the criminal defence lawyer will make ‘submissions’ to the Court (ie the criminal lawyers will say things to the Judge and sometimes hand-up documents).

The Accused can give evidence at the sentencing even if he or she did not do so during the trial. The Judge will then decide the penalty.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should I wear?

You should always dress neatly when going to Court.

If you have a suit, you should wear it.

If not, a shirt and pants or any other neat-looking clothes are fine.

If you are in custody, ask a friend or relative to bring clothes to the gaol.

Will the jury know if I am in custody?

The jury should only know you are being held in custody if you wear ‘prison greens’ to Court.

Needless to say, you will usually create a better impression on the jury if you are not in prison clothes.

How should I act?

Stay calm and composed throughout the trial.

Don’t stare at jurors, don’t make angry faces at the Prosecutor or at unfavourable witnesses, don’t show disagreement (eg shake your head or huff) or amazement (eg gasp or make other noises) if the Prosecutor or a witness says something you don’t agree with (even if they are lying).

In short, act calmly and respectably whatever happens.

What about when I’m giving evidence as a witness?

If you are giving evidence, listen to each question very, very carefully; especially during cross examination.

If you don’t understand a question, say: ‘I don’t understand’ or ‘could you please re-phrase that question’.

If you don’t hear the question properly, say ‘could you please repeat that question’.

Do not be sucked into answering a question you don’t fully understand or didn’t properly hear.

Take your time before answering each question; there is no rule that says you can’t think about a question before answering it.

If you don’t remember something, say: ‘I don’t remember’ or ‘I don’t recall’ or ‘these events happened so long ago, I really just can’t remember’ or ‘It happened so quickly, I just can’t remember’… etc.

The best answers are usually ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘I don’t recall’.

However, if you feel that you really must explain your answer, you can do so; but be very careful not to say anything that the cross examiner might use against you.

What is a ‘voir dire’?

A ‘voir dire’ (pronounced ‘vwah dear’) is when the jury is sent to the jury room (a separate, private room) whilst the criminal lawyers argue about the law.

When the criminal lawyers have finished, the jury will be brought back into the Courtroom and the trial will continue.

Several ‘voir dires’ will normally take place during any jury trial.

Why are ‘voir dires’ held?

Voir dires are held to determine legal issues, such as whether certain documents are admissible under the rules of evidence.

For example, if the Accused gave an ERISP (a record of interview to the police), a voir dire may be held to determine what parts of the ERISP transcript, if any, are admissible as evidence.

Parts or all of the ERISP transcript may be inadmissible if the police failed to follow certain rules, or if they asked questions that were improper.

Voir dires may also be held to discuss matters such as: how a Judge will ‘direct’ the jury about the law; if and how jury questions will be answered; the types of questions permissible during ‘re-examination’, and any other matters involving the application of law.

How is the jury ‘foreperson’ chosen?

The foreperson is selected by the jury panel in the jury room soon after empanelment.

There is no formula for selecting a foreperson; the jury itself must decide how he or she will be chosen.

They may, for example, ask for candidates and have a vote, or they may have a ‘lottery’ or draw straws, or they may choose a person who has already served on a jury panel, or they may just pick the person with the smallest feet; whatever they like!

Does the ‘foreperson’ have more power than the other jurors?

No. The foreperson’s role is merely as a spokesperson for the jury; he or she has the same power as any other jury member; nothing more, nothing less.

Does the jury get to see the witness statements contained in the police ‘brief of evidence’?

Not normally.

Statements contained in the ‘brief of evidence’ (which is the stack of documents collected by the police and given to the Defence some time before the trial) are usually never seen by the jury.

Rather, the witnesses who gave those statements must attend Court personally and give their evidence through questioning.

Only in very rare circumstances are such statements admissible as evidence; namely, in certain cases where the witness is absolutely not available. In such cases, the jury will see that particular statement only.

Any ‘brief documents’ that aren’t witness statements (eg medical or forensic reports, drug analyst certificates, photos, sketches etc) must be ‘tendered’ by either the Prosecution or Defence and ‘admitted as evidence’ before the jury gets to see them.

When and how can documents and other items be ‘tendered’ and ‘admitted’ as evidence?

Documents, video’s, photos, weapons, & any other items can be ‘tendered’ (handed up to the Judge) at any stage of the Prosecution or Defence case.

If a thing is to be ‘tendered’, the tendering party (eg the Prosecution) will say ‘I tender’ followed by a brief description of the item.

The item will then be shown to the other party (eg the Defence) who will say either ‘no objection’, or something like: ‘I object, Your Honour’ followed by the reason for the objection.

If there is an objection, a ‘voir dire’ will often be held to decide whether or not the item is admissible. If the item is admitted as evidence, it will be marked as an ‘exhibit’ eg ‘exhibit A’.

As a general rule, an item can only be tendered through a witness that can verify the item.

For example, an ERISP video (ie the videotaped police interview of the Accused) will usually be tendered whilst the police officer who conducted the ERISP is giving evidence.

Similarly, a weapon found at the crime scene will be tendered through the police officer who found it, and a medical report will be tendered while the doctor who prepared it is giving evidence.

Items cannot generally be tendered without a witness to verify them at trial.

Does the jury have access to exhibits?

The Jury will have access to an exhibit only if it was admitted into evidence while the jury was present.

If the exhibit was admitted during a voir dire, it will remain part of the voir dire only (eg ‘Exhibit B on the voir dire’); the jury will not have access to such an exhibit unless and until it is later admitted while the jury is present.

Does the jury get to see the ‘transcript of evidence’ recorded during the trial?

Yes.

The jury can ask for the transcript of evidence (which is a written record of the trial) at any time during the trial.

The entire transcript will sometimes be made available to the jury without request at the start of deliberations, especially in long trials where the evidence is substantial and therefore difficult to remember.

Does the jury get to see the transcript of what was said during ‘voir dires’?

No.

The transcript relating to voir dires must never be seen by the jury.

If, at any stage, the jury requests transcribed evidence (in other words, requests what was said by a witness), the Court must take great care to remove any records of what was said during a voir dire.

What if the jurors can’t all agree?

As stated earlier, until recently the jury’s verdict had be unanimous; in other words, the jury could only find the accused ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty’ if all 12 jurors agreed.

Recently, the law in NSW has changed to allow ‘majority verdicts’ whereby – if not all jurors can agree – the Judge can direct that a verdict be returned if all except one juror agrees.

For example, a verdict of ‘guilty’ can now be returned if 11 jurors vote ‘guilty’ and one juror votes ‘not guilty’.

The procedure is as follows:

If all jurors cannot agree on a verdict a note can be sent to the Judge.

The Court will re-convene and the note will be read aloud.

The Judge will then ‘direct’ (tell) the jury to be patient, to work through all of the evidence, to be considerate of the views of their fellow jurors, and to ask the Judge about anything they are unsure of.

If, after further deliberations, the jurors still can’t agree, the Judge can direct that the jury may return a ‘majority verdict’ (ie an 11 to 1 verdict).

If a ‘majority verdict’ cannot be reached a ‘hung jury’ will ultimately be declared; meaning that the Accused is neither ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty’.

The Judge will then discharge the jury, and the jury will be free to go.

In such cases, the Prosecution will usually prepare a fresh (new) indictment and the entire trial process will start again with a new jury.

Do witnesses have to turn up to Court?

The witnesses will normally receive a ‘subpoena to give evidence’, which is a Court document requiring them to attend Court.

If a witness fails to turn up, the Judge may issue a warrant for his or her arrest.

If the witness is very important, either party (ie Prosecution or Defence) may apply for an ‘adjournment’.

The Judge will then decide whether or not to adjourn the matter until later in the day or to another day.

What if your witness doesn’t say what you expect?

If, during examination in chief, a party’s own witness (eg Defence’s witness) gives answers that are different to what he or she previously said or which are unfavourable to that party’s (ie the Defence’s) case, that party may ask the Judge to declare the witness ‘unfavourable’.

If the Judge does so, the party may ask that witness cross examination-style questions (including leading questions).

How can Sydney Criminal Lawyers® help me?

If you are facing a Committal Hearing or a District or Supreme Court trial, you should contact experienced criminal lawyers to assist you.

A good lawyer will be able to:

- advise you of your rights;

- explain the charges against you;

- explain your alternatives;

- make a bail application for you in Court (if you are refused bail by police);

- help you fill out and lodge a Legal Aid Application form; and

- represent you at your Committal Hearing, or at your District or Supreme Court trial.

Recent Success Stories

- Not Guilty of All Six Charges of Sexual Assault and Assault Occasioning Actual Bodily Harm

- Client Found Not Guilty of All 10 Sexual Offences

- Not Guilty of All 26 Sexual Offences, Including Multiple Counts of Aggravated Sexual Assault

- Not Guilty of Manslaughter

- Not Guilty of Two Counts of Sexual Assault and Two of Indecent Assault

- Not Guilty of All 22 Fraud Charges and Participate in Criminal Group

- Not Guilty of Multiple Sexual Assault and Aggravated Indecent Assault Charges

- Not Guilty of Drug Supply and Proceeds of Crime

Recent Articles

- Do Courts Have to Use Preferred Pronouns for Transgender Defendants in Criminal Cases?

- In What Circumstances Can a Judge Direct a Jury to Acquit the Defendant?

- The New Consent Directions in Jury Trials for Sexual Offences

- Tips For Testifying in Court as a Witness

- DNA Evidence is Not as Reliable as Many Believe it to Be