California Police to Get Nunchucks

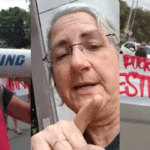

Nunchucks are often associated with ninjas or martial artists like the legendary Bruce Lee. But it looks like they will soon become a standard police weapon, at least in California.

Nunchucks are two solid sticks connected with a cord or chain. They are classified as ‘less than lethal’ and have been used in the past by several US. law enforcement agencies.

The Los Angeles police Department (LAPD) first started using nunchucks in the 1980s as a means of controlling crowds at protests. But the weapon fell out of favour as technology developed, with police switching to tasers to supplement night sticks (batons).

A stated advantage of nunchucks is that unlike traditional batons they can be used to bind the wrists or ankles of suspects – although some don’t see this as a benefit given that police already have handcuffs.

Police will be given 3 days of training in the use of the weapon.

Nunchucks as Prohibited Weapons in NSW

Section 7 of the Weapons Prohibition Act 1998 (NSW) (‘the Act’) makes it an offence to possess a prohibited weapon without a permit. The maximum penalty is 14 years imprisonment.

Nunchucks, or ‘nunchaku’ as they are referred to in the Act, are listed as prohibited weapons under Schedule 1.

Clause 16 defines them as:

“Kung fu sticks or “nunchaku”, or any other similar article consisting of 2 or more sticks or bars made of any material that are joined together by any means that allows the sticks or bars to swing independently of each other, but not including any such article that is produced and identified as a children’s toy.”

Section 6(2) exempts police and other law enforcement agents from the requirements of the Act, provided they are acting within the course of their lawful duties.

Police Weapons and Use of Force in NSW

Police in NSW are not currently issued with nunchucks.

They are, however, equipped with a range of other weaponry including batons, handcuffs, oleoresin (capsicum) spray, tasers and pistols.

The legal use of force is set out in various pieces of legislation and policy.

Part 18 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW) (‘the LEPRA’) says police are only allowed to use as much force as is ‘reasonably necessary’ to exercise their legal function.

Section 230 outlines the “use of force generally”, stating:

It is lawful for a police officer exercising a function under this Act or any other Act or law in relation to an individual or a thing, and anyone helping the police officer, to use such force as is reasonably necessary to exercise the function.

Section 231 outlines the use of force in performing an arrest, stating:

A police officer or other person who exercises a power to arrest another person may use such force as is reasonably necessary to make the arrest or to prevent the escape of the person after arrest.

In assessing whether the use of force was reasonable, a court will consider a range of factors including the nature of the suspect’s conduct at the time, the seriousness of any alleged offence, the officer’s state of mind and the type and extent of force exerted.

Case Study

The case of R v Alkan [2010] NSWLC 1 involved a police officer’s use of a taser on a man in Sydney’s CBD.

The man was walking ‘erratically’ on a busy road, which caused the officer to start following him.

The officer testified under oath that the man refused to follow a direction to get back on the footpath, which was why he tasered the man.

However, CCTV contradicted the officer’s sworn evidence – proving that the man did indeed comply with the officer’s direction and was on the footpath when tasered. The man fell to the ground and was tasered once again when he returned to his feet.

The judge found this to be an excessive use of force, and the ensuing arrest to be unlawful.

This led to the evidence of drugs found on the man after arrest being excluded, and the charges being thrown out of court.

With the proliferation of CCTV cameras and smart phones, it seems that more and more police claims are being contradicted by direct evidence, and that an increasing number of incidents of police brutality are being caught on camera.