Why More Police Won’t Reduce Crime

by Zeb Holmes

A recent Galaxy poll suggested that 82% of NSW residents are in favour of increasing police numbers to confront alcohol-fuelled violence.

In regards to this crowd-favourite measure for stopping crime, the logic is simple but the science is not. If a police presence deters crime, wouldn’t more police deter more crime? Unfortunately, when it comes to police, it appears more is less and the science of crime prevention will require a more nuanced and multi-faceted approach.

Starting from scratch

Police strikes consistently see crime rates skyrocket; in Melbourne in 1923, Liverpool in 1919, Montreal in 1969 and Helsinki in 1976. The effect of adding more officers to an already large police force, however, is less clear.

Deterrence is not a mathematical equation, but is a matter of subjective perception, with police discipline working as a form of panopticon.

This posits a prison where inmates are never aware when they are being watched. This same principle sees retail workers confronted by a ‘secret shopper’ monitoring their performance for every 100 genuine customers.

The fact that the inmate, or retail worker, cannot know when they are being watched means they must act as though they are always being watched.

Would it make any difference though if that secret shopper came once every 80 people instead?

Adding to existing deterrence

Correlation

Australia now has 270 police officers per 100,000 people, up 22% from twenty years ago.

This heavy police presence has accompanied a general drop in criminal activity. A lot can change in twenty years though, and there is contradicting correlative evidence from individual states.

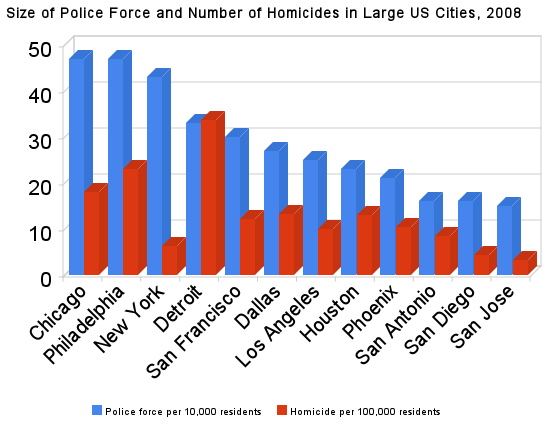

The Northern Territory, for example, has the highest offender rate and highest police presence. The other states are quite inconsistent, an experience mirrored in the US:

This inconsistency demonstrates the danger of correlative findings. The link between police and crime is beset with problems of causality though, with many issues affecting both police numbers and crime, such as economic cycles or social change.

It is also likely that crime causes more police being hired. In such cases, it may look as if more police are consistent with more crime, and it is difficult to know the direction of the effect.

‘Causes’ of crime

When dealing with crime, a ‘cause’ is not an event from which crime inevitably follows.

A ‘cause’ merely independently heightens the individual’s risk of criminal behaviour.

Unemployment, substance abuse, education level, family dysfunction and mental health issues are all strongly established risk factors. Shifting police numbers are more difficult.

The most robust examination has been a 2011 UK review. This paper posits no established link between higher police presence and lower levels of crime as a whole. The existing evidence was inconsistent and inconclusive, in so far as shifts in crime could not be reliably said to be affected independently by police numbers.

There are two major issues here:

1. Problems of ‘rational’ deterrence

The assumption that offenders undertake a rational analysis prior to offending is debatable.

While no conclusive causal link was found, the report did find, “relatively strong evidence for the potential of an effect of police numbers on property crime and other acquisitive forms of offending.” It was estimated that a 10% increase in officers would reduce 3% of this crime.

In comparison, there was no association between police numbers and violent crime, which does not generally involve the same cost-benefit analysis. Violent crime is irrational, fuelled by emotion and generally alcohol or drug use, while the epidemic of domestic violence occurs behind closed doors and immune to public deterrence.

2. Problems of risk-insensitivity

Individuals need to be aware of police numbers to be deterred. One-off and large-scale changes, such as police strikes or a renewed show of force following a terrorist attack, can affect behaviour.

In terms of the potential impact of marginal changes though, a 2014 article relevantly found no relationship between police per capita and perceptions of the risk of arrest, suggesting that increases in police numbers would go largely unnoticed and were not determinative of deterrence.

Cost-Effectiveness

These problems with deterrence theory suggest serious cost-effectiveness issues.

Australia currently spends $10 billion on policing each year. To get some sense of the cost-effectiveness of additional police, let us accept the “strong potential” (although strictly speaking, unproven) link between a 10% increase in police and a 3% drop in acquisitive offending.

On current expenditure, a 10% increase costs $1billion. The total costs of crime are around $36billion per year, with 67% associated with acquisitive offending. A 3% drop those crimes would therefore establish $724million savings.

This rudimentary analysis should begin to paint extra policing as an unattractive investment. With limited public resources, we must consider the opportunity costs of extra police given the hazy evidence of effectiveness.

Alternate investments

A more cost-effective strategy would be a committed investment towards alleviating, rather than just policing, underlying causes of criminal behaviour.

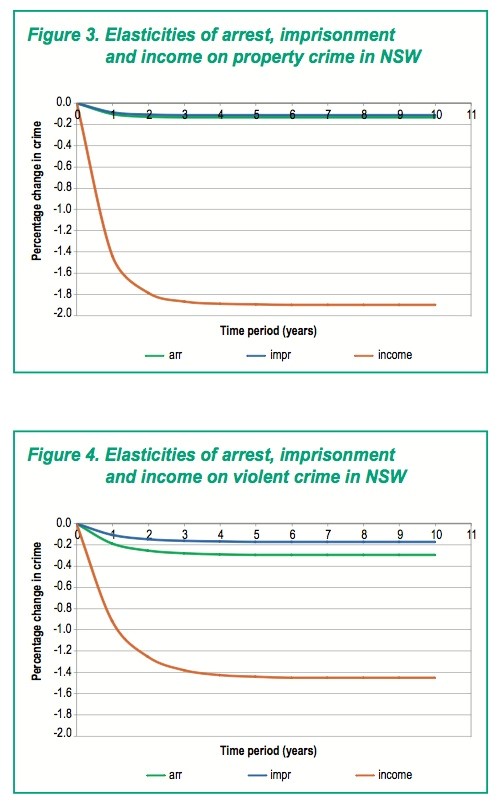

A 2012 BOCSAR report highlights the difference between reactive and proactive spending, stating “Measures that affect the economic well-being of the community provide more potential leverage over crime than measures that influence the risk of arrest.”

A 1% increase to income created a decrease in crime much greater than the corresponding increase in arrest probability. Income effects were 14 times larger for property crime and about 5 times larger for violent crime.

The emerging study of Justice Reinvestment has emphasised this benefit of diverting correctional funds towards preventative community spending. For example, Aggression Replacement Therapy is established to reduce crime outcomes by 8.3%, delivering net benefits of $8.34 for every dollar spent.

This means that for every $1 spent on the unproven outcomes of increasing police numbers, society effectively loses $8 of more effective investments.

Efforts to improve education levels, employment, addiction and mental health issues would all unequivocally reduce the causes of criminal behaviour. In lieu of the ‘tough on crime’ rhetoric, existing evidence does not support the request for increased police presence as it will not reduce crime.

The conclusion is that spending money to alleviate the root causes of crime is a far better investment when it comes to reducing crime than paying for more police.