Exposing the Institutions Responsible: Gerry Georgatos on Cleveland Dodd’s Death in Custody

Tireless social justice advocate Gerry Georgatos has just completed the soon-to-be officially released novel Cleveland Dodd: Child of the Desert Sunrise, which is an account of the death in custody of 16-year-old Yamatji boy Cleveland Dodd, who died in the custody of WA corrective services, as it was detaining him in an adult prison, which is internationally understood to be a human rights abuse.

Cleveland was found unresponsive in his cell early morning on 12 October 2023. The child’s cell was located in Unit 18: a wing of the maximum-security adult Casuarina Prison. Dodd was unresponsive due to a self-harm incident. The senior WA corrective services officer charged with overseeing the child wing on the night Cleveland was discovered was excused from testifying at the inquest.

Dodd passed away in hospital a week later as a result of the incident. His death marked the first recorded in WA youth detention, but not the last. The subsequent coronial inquiry that commenced in April 2024 became the longest running in state history. In handing down an early assessment in July, WA coroner Philip Urquhart announced that he might recommend Unit 18 be shut down.

Cleveland was being held in the adult facility on remand, which meant he had not yet been convicted and sentenced in respect of the crime he was in prison for. The boy was routinely kept in isolation for 22 hours a day, which is another human rights violation in terms of children. Records show that he was held in solitary confinement for 74 days out of a total of 86 that he spent in the adult facility.

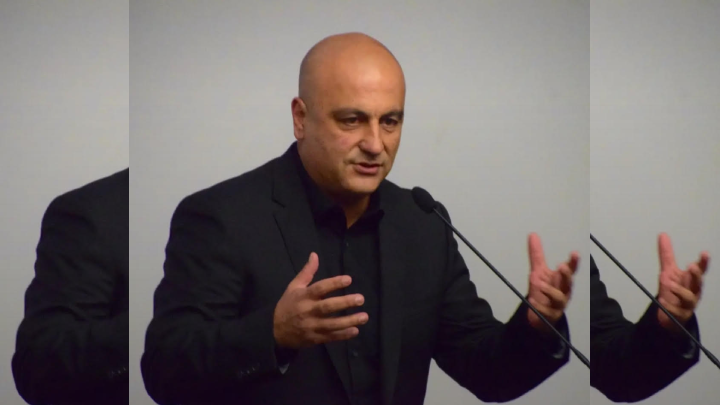

Award-winning journalist

Author of the novel Cleveland Dodd, Gerry Georgatos is a veteran social justice activist, who has long fought alongside First Peoples in seeking justice. Georgatos is also the founder of the National Suicide Prevention and Trauma Recovery Project (NSPTRP). And he’s further assisted those slated to be expelled from the country under the federal government’s extreme deportation laws to remain.

Gerry is too a long-term respected journalist, who has always had a focus on social justice matters, and especially those affecting the First Peoples of this continent. The multi-award-winning investigative journalist is also the co-founder of The Stringer: an independent news site that has been serving to keep the powers that be in check since its inception in 2013.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to NSPTRP coordinator Gerry Georgatos about why he has written this account of the tragic death of a young Yamatji boy in an adult correctional facility, along with the issues triggered by the WA government in its ongoing imprisonment of kids in an adult facility since 2022, and the fact that this means the state is constantly violating children’s human rights.

Gerry, you’ve been assisting individuals and families in respect of their social justice issues for decades now, and this is often in terms of how the criminal justice system has deprived them of any justice.

In the case of 16-year-old Yamatji boy Cleveland Dodd, who died in custody on 19 October 2023, after a week of hospitalisation, following a self-harm incident that occurred in the child wing of adult correctional facility Casuarina Prison, which is known as Unit 18.

You’ve been assisting Cleveland’s mother, Nadene Dodd, in seeking justice after her son died in prison under Western Australian state care.

Gerry, what was it about Cleveland Dodd and his case that led you to write the book Cleveland Dodd: Child of the Desert Sunrise? What sort of a story should the reader expect to encounter in your novel?

The book is dedicated to Cleveland’s mother, Nadene. She both insisted and inspired me to write it.

For most days over the past two years, Nadene and I have spoken about the injustices her son endured — the heartbreak and the devastation that his family continues to live through.

Nadene’s harrowing journey guided every word I wrote. We’ve shared around three hundred conversations — each one returning to Cleveland’s life, his spirit, and the unimaginable cruelty he faced under state care in that stir-crazy cell.

Nadene urged me to tell her son’s story and to include my own two-decade journey of calling out Australia’s children’s prisons.

Cleveland’s death was not just tragic, it was foreseeable — and that’s what haunts me. He was psychologically injured, emotionally battered and physically confined in a stifling cell that broke him. His death, like so many others, could have been prevented. That foreseeability — that knowledge that we can see these deaths coming and still fail to stop them — is what compelled me to write this book.

This book is both testament and memoir — a chronicle of Cleveland’s life and a call to conscience for the nation. Nadene hopes that through Cleveland’s story, change might finally take root — reforms that should have come decades ago, reforms that could have given him a chance to thrive instead of perishing in a place that should have been a bastion of care, not cruelty.

Cleveland was only sixteen — a boy, a son, a heartbeat in the dark — silenced too soon behind the steel bars of a system that was meant to protect children, even those it confined. Cleveland didn’t die because the world ran out of chances, he died because the world refused to give him one.

I want to change laws, push through reforms, transform the inhumane to the humane.

The book is also a forensic look-in to what occurred, what cost two teen lives within 10 months of each other. The reader can expect the truth with this book.

Cleveland Dodd: Child of the Desert Sunrise has just been released. What sort of story should readers expect to encounter in picking up your book?

Forgive me for being visceral with righteous sorrow and moral force. I am angry. I wrote the book in ten weeks because Nadene wanted it published prior to the sad anniversary of his passing two years ago.

I pushed through Parkinson’s Disease, typing with one finger. Readers can expect the facts — and accountability.

This book carries personal reflection, historical context and an unflinching appeal to the conscience of every reader. It is not just an account of one boy’s life and death, it is a call to awaken the soul of a nation.

Every word feels co-authored by Cleveland’s mother, Nadene. Her spirit — and the spirit of her beloved eldest child — sweeps through each page and weeps through every line.

There are moments in history, both national and deeply personal, when a death is not merely a death but a rupture — when a child’s last breath calls to account the conscience of an entire country. Cleveland’s death is one such moment.

Cleveland was a child — sixteen years old — full of the restlessness and wonder of youth yet burdened with the pain and shadows of those failed by our systems.

On 12 October 2023, he suffered an ordeal that should never befall any child, let alone one in state custody. His cell became his tomb — a place meant to correct that instead extinguished his future. He died under watch, yet unwatched. Supposedly kept safe, yet safety never came.

After being placed on life support on 12 October, his family was called for last rites and final goodbyes. Cleveland took his last breath at 10:14 pm on 19 October 2023. I was there, I will never forget. His final light faded within the concrete walls and cold floors of a dungeon that had no place for a child. His eyes closed in that cell, never to open again.

I wrote this book in grief, in fury and in honour — but also in hope: that it might shatter the silence surrounding Cleveland’s life and expose the institutions responsible for his death.

His story is not his alone. It is the story of countless children — disproportionately the children of First Peoples — trapped in a punitive system that criminalises poverty, trauma, disability and cultural survival. Prisons are a classist tirade.

This book is for readers ready to confront uncomfortable truths. It is for those who believe justice must reach beyond coronial inquests and courtrooms, into the heart of our society. It is for the policymakers who still hide behind procedure, the journalists who move on too soon, and the politicians who offer condolences instead of change. And above all, it is for every family who has buried their young far too soon.

The inquest into Cleveland’s death in custody took place in December 2024. WA coroner Philip Urquhart handed down an early assessment of it in July, which raised issues around the crisis in youth justice in WA and how that contributed to the boy’s death.

Cleveland was also repeatedly held in solitary confinement, which is a practice that international standards recommend not be imposed on children. Cleveland is not the only teen to have been subjected to isolation in WA.

You’ve also been involved in organising a class action against the rights abuses of WA’s only child facility, Banksia Hill.

What did you learn about the youth justice system in WA when writing the book? What does it convey to the reader about the WA youth justice system?

The inquest into Cleveland’s death was the longest in Western Australia’s history — stretching from April 2024 to July 2025 — yet also the fastest to be convened. It happened because of the relentless pressure, the sustained voice in the media, the refusal to let this tragedy fade.

But what I saw in that courtroom, I’ve seen before — with Miss Dhu, with Mr Dungay Junior, with Ms Day, with Ms Mandijarra, with Mr Ward — and with so many others. The names change, but the story does not.

Across Australia, eighteen children have died in custody in youth or prison settings. Cleveland was the first in Western Australia. Ten months later, there was another — a non–First Nations child — and that second death only deepened the ache, the horror, the realisation that even Cleveland’s death had not brought the reform we cried out for.

I lament what the Coroner’s Court has become. The Coroners Act 1996 (WA), like its counterparts nationwide, limits the pursuit of justice.

The coroner stands at the threshold of death, tasked with probing its meaning, yet confined to recommendation rather than accountability. The coroner can examine, inquire, and report — but cannot prosecute, cannot compel responsibility for criminal neglect. Within that constraint lies the quiet failure of a system that promises truth but delivers procedure.

I want to see that change. I want coroners to be empowered to compel, to pursue. I want the tens of thousands of lawyers across this nation — not just a few heroic ones — to take up these causes, to use their privilege to serve humanity, not simply profit from licence. Too few lawyers fight for the marginalised, though we have more than a hundred thousand lawyers capable of doing so.

We need an awakening in the national legal conscience — an education in empathy and courage. There are those who already lead the way: Stewart and Danna Levitt, who have launched the Federal Court class action with 2,000 former Banksia Hill children seeking redress: George Newhouse, Claire O’Connor, Julian Burnside, Geoffrey Robertson, Jennifer Robinson — those who fight like it still matters. I honour them.

And soon I’ll stand beside them as a lawyer myself, completing the College of Law next year. Because this country doesn’t yet have a justice system — it has an injustice system, a punitive carceral regime.

Seventeen prisons in WA. One hundred and thirty-two across the nation. Each a monument to our failure of compassion, to a society that pretends not to see.

We could have been better. We should have been better. But until we are, these prisons stand as steel testimonies to the lives we discarded — to the children we betrayed before they ever had a chance.

Cleveland committed the self-harm that led to his death whilst being held in the Casuarina adult facility, in its child wing Unit 18. Keeping children in adult correctional facilities is against international standards.

What is the issue with Unit 18? Why have kids in WA been put in the adult facility for so long? And why is it a problem to put children in adult prisons rather that the nation’s child facilities?

I’ll be searingly raw but hopefully lucid. Unit 18 is not a “child facility” — it’s a holding pen, a corral of human misery.

It’s where children who have already been failed at Banksia Hill — the state’s only youth detention centre — are sent when that system collapses around them. It is a place of degradation and despair. Every single child sent to Unit 18 has effectively been given up on. One hundred percent of them go on to adult incarceration.

What does that tell us? It tells us that rather than surrounding these children with more help, more care, more support, we strip it away. Instead of surrounding them with nurturers, mentors, seasoned youth workers, psychiatrists, psychologists, teachers and social workers, we send them to a concrete cell and call it justice. The state’s message is clear: you are not worth saving.

If Banksia Hill had been what it claimed to be — a place of rehabilitation and healing — then Unit 18 would never have existed. Its very existence is proof of failure. If Unit 18 operates, we are accepting the unacceptable. It doubles down on cruelty and codifies despair.

I warned that the creation of Unit 18 would be an “insane rush” — another prison built instead of a system of care. It defocuses government attention from the vital needs of the children and guarantees further failure.

Now instead of dismantling this disgrace, the state plans to build yet another so-called “world’s best practice” youth prison — a $150 million monument to misunderstanding — right next to Banksia Hill. But a new building cannot reform a broken philosophy. The moment you design a place to incarcerate children, you’ve already failed them.

We’ve seen this before. In 2013, after riots at Banksia Hill left most cells damaged, seventy-nine children were transferred to Hakea — an adult prison — prompting outrage and litigation. Reports were damning. Promises of reform followed, yet here we are again.

Nothing has changed in any meaningful way in twenty years. In truth, in thirty five. From Longmore to Rangeview, from Banksia Hill to Unit 18, the story is the same: unrehabilitative, punitive, failing generation after generation.

Unless there is a complete reimagining of youth justice — one grounded in care, community, and restoration — we will be standing here again in ten or twenty years, lamenting new names, new funerals, the same failures.

I hope I’m wrong. But hope, without courage and change, is never enough. Until we transform these bastions of cruelty into pillars of humanity, we will remain a society that punishes the wounded and calls it justice.

And lastly, Gerry, in having written Cleveland Dodd, what sort of influence do you hope it has in terms of influencing reform of the youth justice system in your state? And how else do you hope this book impacts?

I hope this book helps keep a mother’s child alive — not just in memory, but in the hearts of all of us.

I hope it gives Nadene some small solace in knowing that Cleveland’s life will continue to speak, to inspire, to call us to account. He’s not forever gone. His story will outlive us all.

Part of the proceeds from this book will go toward helping Cleveland’s siblings attend boarding schools — to give them the education and opportunity to navigate their dual identities: as First Peoples and as participants in the broader Australian community. To give them the hope that was ripped away from Cleveland, the eldest sibling.

Some proceeds will also ensure that Cleveland has the gravestone his mother envisions — at his resting place, in Meekatharra — so that the world will remember him properly, with dignity and love.

I have seen change happen before. I’ve fought for and achieved reforms — had laws amended, rewritten, humanised. I’ve seen the power of persistence. If we can galvanise the many into the multitude — if compassion becomes collective — we can overhaul every system that diminishes the human spirit.

In the book, I look to the Nordic models — Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands — nations that have reimagined justice. They have built systems that turn lives around instead of locking them away. They have reduced recidivism, humanised rehabilitation and shown that safety and compassion are not opposites. That is the reckoning we need — a community transformation born of courage and empathy.

I’ve lived this work. I’ve written prolifically about it. I’ve stood with the vulnerable, walked with those whom society cast aside. But I want to end on two points that mean everything to me.

One of the chapters in Cleveland Dodd: Child of the Desert Sunrise was written by my daughter, Connie Georgatos, a psychology student, who has worked with me in transforming young lives — including within prisons. Her chapter is titled The Media Campaign, the Indelible Memory, and the Making of Justice: Cleveland Dodd, Banksia Hill, and the Battle for the Nation’s Conscience. She wrote words that pierced me:

“There are times in the arc of a society when silence becomes complicity, and complicity becomes a crime — not merely of omission, but of wilful indifference. In the underbelly of Australia’s institutional landscape, that silence hovered for decades over a place that was never meant to be what it became: Banksia Hill — a site imagined as rehabilitation but turned through government inertia and bureaucratic cruelty into a corral of suffering, a trapdoor for childhoods. And through it all, year upon year, a lone voice, sometimes joined by others but often battling the winds alone, refused to let the story fade — the voice of Gerry Georgatos.”

My daughter has lived beside me, seen the pain, and now continues that struggle herself. Her words give me hope — that change can come not from power, but from conscience.

She concluded:

“To truly understand how this campaign came together is to understand how social reform is born — not in parliaments alone, not in courtrooms alone, not in the slow churn of legal reform, but in the consciousness of the people, awakened by the untamed force of story. When media rests in the hands of justice seekers, rather than power protectors, it becomes a torchlight that guides the way through the abyss.”

That’s what I believe this book is — a torchlight. It’s Cleveland’s light. And through that light, I hope this country finally learns to see.

On publishing Cleveland Dodd: Child of the Desert Sunrise, I want to acknowledge and thank all the potential publishers who were prepared to consider the manuscript. Their willingness meant a great deal.

But this was a time-sensitive story — and time was not on our side. We needed this book in the world now, in 2025. We couldn’t wait until 2026 or 2027 or 2028. That would not have done justice to the spirit of Cleveland, nor to the children who must be safeguarded from the fate that claimed him.

The first publisher I approached was exclusively sent the manuscript. Ten weeks later, on 18 September 2025 — inadvertently, the date that would have been Cleveland’s eighteenth birthday — I received their reply. It was, in effect, a rejection, though not because the work was unworthy, rather, 2027 was the earliest year they could publish. But Cleveland couldn’t wait. Justice couldn’t wait.

That day reminded me of 1 December 2023, when Cleveland’s funeral was nearly derailed. The Department of Corrective Services had refused to allow his father to leave Greenough Prison to attend, citing “safety concerns.” I rejected those claims then, and I reject them still.

That day, hundreds of families and supporters gathered, ready to protest outside the police station and courthouse until both parents could attend their son’s farewell. It seemed impossible. But guided by Cleveland’s spirit, I pressed on. After urgent appeals — including direct communication with premier Roger Cook — permission was granted. Cleveland’s father came. And Cleveland was laid to rest in the desert sands, in the cathedral of Country, with both mother and father present.

That same resolve guided the decision to publish this book now, in 2025 — not years later.

Cleveland’s voice must be heard now, not in some distant future. This work is dedicated to saving young lives, so that no other child meets the fate he did. Time sensitivity is not a luxury, it is the very essence of justice for Cleveland and for the children he calls us to protect.

So, I published the book myself. I financed the printing, the first, second and third run, and the distribution. The official launch will take place on 1 December 2025, the second anniversary of Cleveland’s burial.

Already, thousands of copies have sold, and the demand continues to grow. Those sales have covered the cost of the headstone Nadene wanted so deeply for her son — a small but profound piece of closure.

After the launch, I may hand the book to a publisher for wider circulation, so that Cleveland’s story endures for posterity. But it was vital that it reach hearts and hands this year. It was never about commerce — it was about conscience.

For anyone who wishes to obtain a copy, you can email me at directly at coordinator@suicidepreventionproject.com.au, and I will respond promptly. For media enquiries, I can be reached on 0430 657 309.

And to you, Paul — my brother, my comrade in arms — thank you. You have stood in truth when others have stayed silent. You have run story after story on Cleveland, and on so many others who would have remained voiceless if not for you. You remind us of what journalism can still be — a torch in the dark, held high for justice.