Jury Asks Dead Man if Defendant is Guilty of Murder

How would you feel about a dead person being asked to decide your fate if you were on trial for murder?

It’s certainly not the most conventional, or recommended, method of deciding guilt or innocence, but this was exactly what happened in the UK case of R v Young [1995] QB 324.

Stephen Young, a 35-year-old man, was accused of a double murder. The dead bodies of Harry Fuller and Nicola Fuller were discovered in their home. Both had been shot, and it wasn’t long before Young was accused of the offence.

A trial was conducted and the jurors ultimately retired to consider their verdict. They could not reach a unanimous decision and so they were taken to a hotel for the night. The next day, the jurors returned to court and unanimously voted ‘guilty.’

But what had happened at the hotel that night?

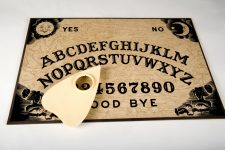

Evidence later came out that several of the jurors drank more than they should have, and four of them decided to use an Ouija board.

After supposedly making contact with several dead people known to the jurors, the glass being used as a pointer indicated that the deceased Mr Fuller was present.

The glass then spelt out that Stephen Young had killed him and his wife. After giving more information about the case, including the type of weapon used, the glass finished with: ‘vote guilty tomorrow.’

This encounter disturbed the jurors, causing one of them to break into tears crying. The four agreed not to tell anyone what they did – but they ended up telling one other members of the jury over breakfast.

In court, Young was unanimously found guilty.

How did the secret get out?

Like in Australia, jury deliberations in the UK are supposed to be secret – and no one, not even the court, is allowed to inquire into the decision-making process.

But in this case, the jury member who was not involved in summoning the deceased was concerned enough to consult a lawyer. He made a statement, and the lawyer then spoke with the counsel for Young.

Unsurprisingly, Young appealed on the basis of that information.

Can the court open the door of juror deliberations?

As already stated, jury deliberations are supposed secret, and not open to the scrutiny of the court, which created a significant hurdle in this case.

If the court didn’t have the power to investigate what happened that night in the hotel, it was obvious that the court couldn’t correct what might have been a miscarriage of justice.

The court assessed the three possibilities:

1. That the court was permitted to inquire into the behaviour of the jurors that night in the hotel and what happened in the jury room afterwards;

2. That the court was permitted only to inquire into what happened in the hotel but not the jury room; or

3. That the court could not inquire into the jury’s activities at all

In the end, the judges decided that the conduct of the jury at the hotel was indeed open to scrutiny, because that conduct could not be considered ‘deliberations’ given that not all of the jurors were present.

And in this case, no matter what one thinks about the veracity of the messages from the Ouija board, the court considered it to be extraneous material, which is not permitted to be considered by jurors when making their decision.

The court found there was a real danger that the Ouija session may have influenced some of the jurors, and granted Young’s appeal on that basis.

A new trial was ordered, but Young was convicted yet again.

What can NSW juries consider when deciding their verdict?

While most of us would not resort to a Ouija board to decide guilt or innocence, there are strict rules that determine what a jury can and cannot consider.

Juries can only consider the evidence put before them in the courtroom – they are not permitted to do their own research by reading the papers or legal textbooks, or asking the opinion of friends or family, or discussing matters on social media.

Jurors are not allowed to conduct experiments or organise their own excursions to alleged crime scenes.

In fact, all these actions are offences under section 68C of the Jury Act 1977 (NSW), and attract a maximum penalty of 2 years imprisonment and / or a $5,500 fine.