Jury Nullification: Power to the People

Being on a jury is an important civic duty, although it can disrupt work and family commitments.

A jury’s primary role in a criminal case is to decide the facts, and the ultimate question of whether a defendant is guilty or not guilty.

Last month, Michigan man Keith Wood was convicted of a misdemeanor after being caught distributing pamphlets about ‘jury nullification’ outside a courthouse. After initially being charged with a felony, the former pastor’s charge was downgraded to jury tampering.

Mr Wood’s criminal lawyer submitted that his client could not have tampered with a jury that “did not exist” when he distributed the pamphlets, and that his client’s constitutionally enshrined freedom of speech was a defence to the charge in any event.

The proceedings followed a similar case in Denver that saw two protesters face seven counts each of jury tampering for distributing information about jury nullification.

Anonymous’ Campaign

Earlier this week, the online collective ‘Anonymous’ posted an article attempting to raise awareness about jury nullification – which is where juries find a defendant not guilty of a crime they perceive to be unjust despite the strength of the evidence against them.

Anonymous endorses the view held by many anti-establishment groups that jurors have a right to disobey immoral laws.

It wants the public to use jury service to acquit people accused of disobeying laws that are morally disagreeable, such as cannabis laws, laws against assisted suicide and mandatory minimum sentences that bring about unjust outcomes.

How Did Jury Nullification Come About?

Many see jury nullification as a byproduct of two laws that exist in both the US and Australia – laws which protect jury secrecy and safeguard against double jeopardy.

Juries are not required to give reasons for their decision – they are merely expected to reach a verdict of guilty or not guilty in accordance with the law. Jurors cannot be punished for deciding one way or the other, even if their conclusion does not appear to reflect the state of the evidence.

Combine this with the rule against double jeopardy, which (in most cases) prevents an accused person from being put to trial a second time based on the same facts that got them to court in the first place, and you’ve got a recipe for jury nullification.

Case Study – by Ugur Nedim

As a junior criminal defence lawyer, I represented a man charged with murdering another inmate inside Goulburn prison.

The deceased was serving time for a string of heinous crimes – one of them involving him and fellow ‘5 T’ gang members approaching a pair sitting in a car at a ‘lover’s lane’ on the Georges River, assaulting and tying the young man to a tree, then gang raping and murdering his young female partner in front of him.

The deceased was a powerful person in prison, and had achieved the position of ‘sweeper’. One day in the prison’s tailor shop, he and another inmate tried to drag my client’s friend towards the toilet area. My client grabbed a large pair of scissors and stabbed the deceased relentlessly to all parts of his body – head, body, groin – 67 times in total.

By all accounts, my client paused for several seconds during the attack – at which time the deceased was incapacitated – then recommenced stabbing. This could not be classed as ‘self defence’ under the law.

My client saw a number of lawyers before me. Each of them strongly advised him to offer a plea of guilty to manslaughter, which in my view was the correct advice given the information available to them at the time.

I was later assigned a grant of Legal Aid for the matter and, like I do in all serious cases, subpoenaed a whole range of documents – including 3,000 pages of prison medical and administrative materials, which I meticulously reviewed.

Low and behold, the medical files contained reports predating the killing which suggested that the deceased had sexually assaulted my client on at least one prior occasion, and had reported that the deceased had been doing this to other inmates. When I confronted my client with this information, he broke down in tears – scarred and ashamed.

Armed with this information, we proceeded to trial at Darlinghurst Supreme Court where I instructed now-retired criminal defence barrister Andrew Barrie.

Our case strategy was to put as much disparaging information about the deceased before the jury as possible – his despicable past crimes, his abuse of power in prison and the evidence about his conduct towards my client. It worked. Despite the fact that 67 stab wounds with a pause in between would amount to excessive self defence (at best) the jury found my client not guilty of the single charge against him – murder.

Watching the jury during that trial, it was apparent they were disgusted with the deceased and his conduct – to the point where they perhaps thought his demise represented justice, despite the state of the evidence.

This is my most vivid memory of a situation which might fall into the category of ‘jury nullification’.

Power to the People?

Hundreds of laws have been passed in recent years which enhance State power at the expense of civil liberties.

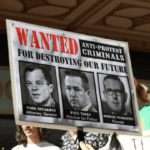

Federal laws which make it a serious crime to disclose information about ‘special intelligence operations’ (ie anti-terrorism raids), ‘offshore boat operations’ and human rights abuses in detention centres may be seen as unjust, as well as the NSW government’s new ‘anti protest’ laws.

There are also situations where jurors might sympathise with the motives of perpetrators – such as those who assist terminally ill people to commit suicide, or even the recent case where a Newcastle man killed an intruder.

Although jury nullification requires jurors to ignore a judge’s directions, the public’s access to materials like those published by Anonymous could just lead to people power prevailing inside the courtroom in the face of unjust legislation.