“A Legal Quagmire”: Georgatos on Incarcerating Youths in Casuarina Adult Prison

The WA Department of Justice transferred 17 youth detainees aged from 14 to 17 into Casuarina Prison, an adult maximum-security facility, on 20 July, as the conditions at their former place of detention, Banksia Hill Juvenile Detention Centre, were reaching crisis point.

WA Justice director general Dr Adam Tomison told the media that his department had no choice but to relocate the children to the adult facility due to the “unprecedented destruction of living quarters and infrastructure and threats and attacks on staff”.

But this doesn’t present the whole picture, as the president of the WA Children’s Court recognised earlier this year that WA’s only children’s prison has been treating its detainees, who can be as young as 10-years-old, in such a barbaric manner that it’s producing a similar response in return.

Indeed, whilst the environment within the centre may be rising to fever pitch right now, the notorious youth gaol has been abusing those sentenced to spend time inside it for decades, which has led it to become the subject of a class action raised on behalf of its former child inmates.

From harm into more

WA Children’s Court president Judge Hylton Quail said, as he presided over the case of a 15-year-old Banksia Hill detainee in February, ““When you treat a damaged child like an animal, they will behave like one and if you want a monster this is how you do it.”

The boy, who was facing multiple assault charges relating to incidents inside the prison, had been kept in a tiny isolation cell with an observational wall for 79 of 98 days – 33 without the required 30-minute break – during the last summer, which saw temperatures in the extreme.

Fast forward to mid-year and the conditions at Banksia Hill have not improved, hence the transfers, which a month later, have seen 3 suicide attempts and 13 incidents of self-harm at the standalone centre known as Unit 18, at Casuarina Gaol, where the boys have been placed.

While former WA Children’s Court president Denis Reynolds has suggested that the transfers to the prison compromise the work of the court, as, when judicial officers sentenced these teens, they did not factor in to the sentencing process that they would be held in an adult facility.

Righting the wronged

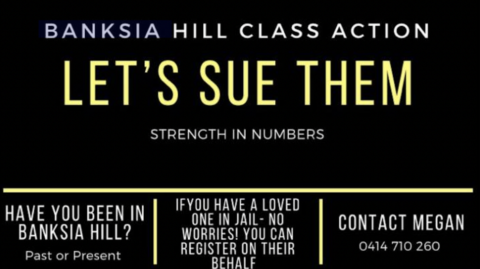

Restorative justice advocate Gerry Georgatos is one of a group of prison abolitionists, who launched the Banksia Hill class action in August last year.

The civil case currently involves 600-odd former detainees seeking just compensation for the rights abuses they suffered in the facility.

The last reported custody statistics for the centre show that in the 2020 September quarter, there were 83 youth detainees locked up inside Banksia Hill, which included a stark overrepresentation of First Nations children, with 57 inmates, or 69 percent, being Indigenous kids.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to National Suicide Prevention and Trauma Recovery Project coordinator Gerry Georgatos about the conditions the youths are facing in the adult facility, the need to raise the age of criminal responsibility and how the Banksia Hill class action is progressing.

When we last spoke about Banksia Hill Juvenile Detention Centre in early March, District Court Judge Hylton Quail had just implied the centre was treating youth detainees like animals, which was resulting in the behaviour one would expect from animals.

On 20 July, 17 Banksia Hill youth detainees, aged between 14 to 17, were transferred to Casuarina Prison: a maximum-security facility for adults.

Gerry, how did it get to the point that youth detainees had to be removed from Banksia?

Three 14-year-olds and three 15-year-olds and eleven 16- and 17-year-olds were relocated to Western Australia’s largest maximum security adult prison.

The fact this occurred is squarely the result of the WA government refusing to invest in hope for these children.

Refusing to invest in wide-remit restorative approaches, refusing to invest in one-on-one mentoring of these children on a seven day a week basis, refusing to invest in the transformational.

We must question why year-in, year-out, there are crises at Banksia Hill? Why between 60 percent to 70 percent of the children when they’re adults offend and are imprisoned? We must shift the focus onto why Banksia has failed its original intention as rehabilitative.

There is a long roll call of services on the inside of children’s prisons sanctioned to help – there are 17 children’s prisons Australia-wide.

A review of the services at Banksia may not only lead to reforms at Banksia but be tapped into by other children’s prisons.

It’s a roll call of far too many duds abysmally failing our most vulnerable children. Some of the services are destined to fail the children because they’re not allowed to do more. Some fail because they don’t know what they’re doing.

It’s the lost leading the lost. Many fail them because they’re not capable of rapport. To some, it’s just a job.

The focus must shift to an independent-as-possible robust public review of the services, programs, the systemic failures, a tabling of unmet needs and the ways forward.

We have heard heaps about the harrowed lives of the children – of their sufferings. So, when are we going to change what Banksia Hill is predominantly about? From a carceral experience to the transformational.

Too many snouts in the trough. Carpetbaggers. It’s got to be called.

We need to reform this prison-dwelling-place to a bastion of tenderness. Then we can speak to the children of saving, of change and love instead of signalling aloneness and ruination.

There are too many lives lost of young ones, post-release.

Sending youths to adult prisons is widely understood as problematic, but can you elaborate on why this is the case? And does it conflict with the original sentences these teenagers received?

These children are screaming for help.

Children, vulnerable children – all of them critically vulnerable – many with neurocognitive impairments, some who are orphans, some totally abandoned, some who are homeless and transient.

Children who’ve seen abysmal suffering, unimaginable to most. Many see each day as their last, so they treat each as if it is.

Locking them up at Casuarina is sending the message, “We’ve given up on you.” They are further invalidated.

They weren’t remanded or sentenced by the Children’s Court to the Casuarina site but to Canning Vale’s Banksia Hill children’s prison. So, there should be deliberation about whether that’s judiciously conflictual.

There should be deliberation about whether it was legally permissible to relocate them to Casuarina without the Court deciding whether this is permissible.

We’ve seen this year the Children’s Court on several occasions refuse to remand children to Canning Vale’s Banksia Hill because they viewed a demise of conditions.

It’s potentially a legal quagmire. But most importantly we must scream once again, “When will Banksia become a bastion of nurture, instead of a holding pen?”

There’s an injunction on the way, imminent, and if successful, the children will have to be relocated back to Canning Vale’s Banksia Hill.

It’s a moral abomination that these children have been corralled in an adult maximum-security prison.

The more troubled a child, the more nurture they need. Society in general is not allowed to treat children akin to such manner.

Nurture is not what they have in Casuarina – the express purpose was to segregate, separate and isolate these children.

WA has the second highest youth incarceration rate in the nation. Who are the youths that are ending up in Banksia, the state’s only youth prison?

They are WA’s most vulnerable and most at-risk children. The forgotten children of Banksia, as I describe them, are our most impoverished, most traumatised children.

The majority are without a chance at a good life from the beginning — born into multiple disadvantages, into cruel unfairness.

I argue, 100 percent of them have experienced major traumas. A significant proportion must be recognised as having no safety nets — in fact, many have no parents. Many come in from transience and homelessness and many return to such loneliness.

In my view, governments spend more on criminalising a child – whether regional or city-living – than it would cost to provide local, wraparound services for them and their families where possible.

Children must not suffer before our eyes. I’m a prison abolitionist but if there’s going to be a Banksia, it must be filled with love and joy, salt-of-the-mentors, with trust and hope. We must speak to them with calm stillness, and they will turn their eyes to ours.

Their pasts must be dulled to mists in their memories. Entreat them with love, bend our heads to them, listen to them and do not interrupt with answers.

Sit near them, let their tears fall. Let them pour out all their tears. The weeping will end with healing.

I can’t talk other ways, or specific banalities, but of the narrative of change – because without this focus we are going nowhere fast.

I can’t tone down my language and betray children. Not just Banksia, but all children’s prisons – did we learn ever so little from the Royal Commission into Don Dale?

We change Banksia, we’ll change all the child prisons. There are more than 800 Australian children imprisoned across the nation.

Disproportionately, 49 percent are First Nations children, despite First Nations children comprising 5.8 percent of Australia’s child population between the ages of 10 to 17 years.

Juvenile prisons are not a First Nations incurred problem. I’ve got to emphasise this.

The disproportionality of First Nations children incarcerated is more than a correlation, but directly attributable to the unaddressed catastrophic levels of impoverishment of First Nations people, borne of the sins of the invaders and perpetuated in various abhorrent forms by one government after another.

The long road to equality remains horizonless for many.

More than 100 of WA’s children on any night are hovelled in Banksia. Disproportionately, 69 percent are First Nations. Annually, at least 500 unique child prison entrants come in and out of Banksia Hill. More needs to be done for our most vulnerable children.

Banksia Hill is as poor as it gets regarding restorative, transformational, psychosocial and psycho-educative programs and age-sensitive nurture.

I must also note, when I refer to restorative, I am not arguing restorative justice per se which brings in the victims of crime. This can be done separately as part of the mutual reckoning.

I’m talking about restorative work, in rebuilding or building a life, in trauma recovery, in improving the life circumstances of an individual, in developing a positive self, a forgiven self, an understood self, which includes shared understandings, in supporting individuals to stabilisation, education, employment and wisdom.

Restorative approaches and works end discriminations, demonisations, aberrances and reoffending.

We must emphasise that these children were born into unfairness and disadvantage. Dog-tired, crazy by their insufferable youth. They cannot do their very best without support. Many have no one. I’ve met no child who couldn’t be helped.

In the last two decades, there have been more than 100 deaths after custody post-Banksia – mostly by suicide. The nation should know.

We cannot accept silence because we fear persecution. We cannot choose to be safe in our heated homes while children are gaoled, released to the streets and deserted. Children dying by their own hands should be furthest from their minds.

The campaign to raise the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14 continues around the country. Tasmania has raised the age. Queensland just voted down a bill attempting to.

But some maintain that 14-year-olds shouldn’t be locked up in child prisons either. You’ve worked closely with adults and youths inside gaols. What’s your point of view in this regard?

Over the years, Productivity Commission reports on government services identified Banksia as failing one-in-four children in its care, in that they were not receiving an education. Quality education is a missed opportunity altogether at Banksia.

Assaults were recorded on average every ten days. Mentoring is the major missed opportunity at Banksia. This is inexcusable — in fact, it is reprehensible. Assaults have increased.

Even worse, on average at Banksia, a child self-harmed every two days. In my many years of supporting our most marginalised vulnerable children, in general, kids leaving Banksia come out no better or even worse. Self-harming has now increased – effectively on average, daily.

Children as young as ten should not be incarcerated, not gaoled, which is what juvenile detention is – gaoling in a prison, sleeping in dungeons.

Testimonies to me and my colleagues, Megan Krakouer, who holds a Bachelor of Laws, and my law student daughter Connie, from hundreds of former and recently released Banksia detainees describe the same fails and horrors.

For how long are the same services going to be allowed to keep on failing these children? There should be an independent-as-possible public review of the service providers in and outside of Banksia.

We have an Australian Senate, which in 2019 repugnantly voted against raising the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14.

Had they voted to raise the age, governments would have been compelled to fund substantive social supports.

Queensland has also recently betrayed 10, 11, 12, 13-year-old children, voting against raising the age of cognitive criminal responsibility.

The Senate voting to keep gaoling 10-year-old children further solidified this nation’s reputation and reality as one of the world’s murkiest.

Banksia isn’t even an interim safety net. The Banksia experience, in general, diminishes children to the worst of themselves, fast-tracking disaster — some paying with their lives — suicide, grievous misadventure, drugs and unnatural deaths.

How are the seventeen youths who’ve been transferred to Casuarina coping in the adult prison system? What sort of conditions are they facing?

There are now 11 youths incarcerated at Casuarina’s Unit 18. Eight are First Nations, three are not.

One child has been returned to Banksia Hill in Canning Vale after his parents lobbied relentlessly. Five have been released by the Children’s Court – on bail orders.

It is difficult to not conclude a harsh punitive experience — a culture of punishment. Punishment dished up in one form or another. Punishment soaked up until one is broken.

We do not listen to the endless reports. We do not listen to the lived experience. Legislators preach tough responses on children who commit crimes.

Children screaming for help and instead of listening, inexpert personnel diminish them, albeit inadvertently by most.

In the end, they’re diminished, invalidated and isolated.

Why do we enforce 23-hour lockdowns? Why do we enforce long-term separation from other detainees, from human contact? Why is there a rejection of restorative approaches by proven seasoned expertise?

At Casuarina, the claimed education activities – as low calibre as they are and of short daily duration, believe it or not, 30 minutes a day – well, those education activities have ceased altogether.

They ceased after only several days after the relocation, because of damage to cells by some of the children. The 30 minutes of educational activities are yet to resume.

The hurt is deep and damaging. It goes to the psychosocial, to the cognitive, destroying prospects to a positive self, robbing one of all hope.

What’s missing from the criminal justice system and the penal estate are cultures of understanding and nurture.

Without understanding and contextualising there are no pathways to forgiveness and redemption, to the restorative or to building lives from scratch for those who never had a chance from the beginning of life — born into unfairness and extreme disadvantages.

Hate and anger have filled the prisons — adult and children’s prisons — with the mentally unwell, the most vulnerable and the poorest. Treated as no good, they play out in undesired ways, anger follows — and the storm is wild.

Hate can never achieve what love can.

And lastly, Gerry, last year, the Banksia Hill class action was launched, which involves former detainees suing the WA state in relation to their treatment whilst locked up in there.

You and your NSPTRP colleagues Megan Krakouer and Connie Georgatos are working on the action, which is being led by Levitt Robinson Lawyers.

How is the legal action progressing?

We have the social justice warrior lawyer, Stewart Levitt leading a class action in pursuit of compensation for the forgotten children. Stewart’s daughter, steadfast stalwart Dana Levitt is the class action’s managing lawyer.

A successful win in the court would ultimately compel governments to humane ways forward instead of a children’s prison, to a plethora of reforms and to a firmament of social care systems and supports.

A letter of intention has been presented to the state government. Testimonies are being collected from former detainees of Banksia Hill, which was established in 1997.

There are now more than 600 plaintiffs. Hundreds of testimonies describing much the same goes to corroboration, the heart and soul of evidence.

I estimate more than 10,000 children have gone through Banksia. It’s my assessment the class action will culminate in thousands of plaintiffs.

The class action has been filed in the Human Rights Commission on various grounds of discriminations. It will also be filed in the Federal Court later this year.

I want to see adequate compensation for each of the affected to have a better chance at a good life.

I want to see the unfairnesses of life many were born into, addressed by some lifechanging compensation — and by the imperative of validations of what they have been through, unsupported till now.

Being heard matters: it connects us all. I have been seared emotively by many just wanting to be heard, wanting to see historic sweeping changes. There have been a lot of tears, outpourings and some healing by the forgotten children being heard.

If we win in the courts, precedents will be set for changes and reforms not just in WA, but which can be tapped into by every state and territory because we shone the light on Banksia Hill.

One youth said, “I want to be part of history — that my children one day do not finish up locked up like me from 11-years-old. And like my father when he, too, was a kid.”

We have heard many tragic, staggeringly harrowing testimonies, listened to the pain and suffering, to broken souls and seen, first-hand, broken lives.

It is long overdue for our courts and importantly, for the nation to hear in detail the sins, not of the incarcerated, but the sins of a nation that leaves them behind from the beginning of life and of the sins of carceral systems and governments, who betray further children who never had a chance.

If all today’s most vulnerable children and the unborn are to share in hope, the nation’s eyes and ears need to lend focus, not on dissension and whistleblowers, but on loving every child.