Calls for Overhaul of Drug Driving Laws

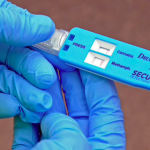

Roadside drug testing was introduced into the NSW setting in 2007. Just like random breath testing (RBT) for alcohol, drug testing drivers was said to be brought in to improve safety on the roads. But, unlike RBT, it doesn’t test for driver impairment. It’s a trace-based program.

The NSW testing regime was modelled on that in Victoria, which tests for the mere presence of just three select illicit substances: MDMA, amphetamines and THC, the psychoactive component of cannabis.

Since July last year, cocaine has been added to the drugs NSW police test drivers for. This was following a campaign to get authorities to include cocaine, as it’s a drug favoured by the rich, while the use of the other three substances is more prevalent amongst the less affluent.

Proponent of the “just say no” to drugs approach, NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian announced in January last year that her government was doubling the amount of roadside drug tests statewide from 100,000 to 200,000 annually.

And this led many in the communities heavily targeted by road drug driving tests to ask why authorities aren’t using a similar method to RBT in order to improve road safety, rather than using this presence-based model as a backdoor way to punish them for the illegal use of drugs.

Not under the influence

“Drug driving laws should be about impairment and not traces,” said NSW Greens MLC Cate Faehrmann. “If people drive high, they should be charged. Because they pose a danger to others. But, road safety laws shouldn’t be used to prosecute people who’ve taken illicit drugs days ago.”

Section 111 of the Road Transport Act 2013 (NSW) stipulates that driving a motor vehicle with the presence of a prescribed illicit drug – cannabis, cocaine, MDMA and amphetamines – in their saliva, blood or urine is an offence.

NSW police officers test saliva for what can be minute traces of these substances. Opinions differ as to how long these drugs can remain present in oral fluid. However, a 2013 US medical report found THC could stick around for up to 3 days for new users and up to 29 days for those using long-term.

Nine days prior

“One person was told that it takes one week for cannabis to get out of their system,” Ms Faehrmann recalled. “They drove nine days later and were still found to have traces in their salvia, when they were pulled over by the police.”

This was the case of Joseph Carrall, who Lismore magistrate David Heilpern found was not guilty of drug driving, as he hadn’t smoked any cannabis for nine days prior to testing. Mr Carrall told the court he followed the advice of a police officer, who recommended he wait a week.

A community in crisis

“People are getting their licences taken off them in regional areas. There’s no public transport, therefore it affects their employment,” Faehrmann told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “If they’re let off by the judge and they’re caught within the following five years, then they’re charged regardless.”

The NSW Greens drug law reform spokesperson stressed that individuals are having their lives impacted, without posing any road safety risk to others. And not only is this taking its toll on the community, but drug driving cases are clogging up the already strained local court system.

Ms Faehrmann explained that the Greens campaign has a particular focus on the Northern Rivers region, which has long been the flashpoint of a NSW police roadside drug testing blitz.

Indeed, a 2017 NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research drug driving report found 470 convictions per 100,000 drivers in that region, compared with the state average of 93. While all separate Sydney metropolitan regions ranged from between 7 to 27 convictions per 100,000.

Time for an overhaul

When the NSW Legislative Council resumes, Ms Faehrmann plans to move a motion to establish a review of the state drug driving laws. “We’re calling for the laws to be repealed,” she explained. “And for there to be a parliamentary inquiry into their effectiveness or otherwise.”

Ms Faehrmann pointed to the Victorian Drug Law Reform Inquiry report and its recommendation to investigate European drug driving models that utilise impairment levels and thresholds for different substances that when exceeded have been scientifically proven to make the roads more dangerous.

European countries test for impairment

The Netherlands implemented a drug driving regime in July 2017, which tests for drug levels in a driver’s system to ascertain if they’re a danger on the road. This was modelled on the Norwegian program that’s been operating since as far back as February 2012.

Norwegian police officers test drivers for levels of 20 licit and illicit non-alcohol drugs, which are based on the cognitive performance of “drug naïve individuals”, who have been given a single dose of the range of different drugs.

These drugs include all four drugs that authorities in NSW only test for traces of. It also includes a range of commonly prescribed benzodiazepines that have been shown to be present in the bloodstream of more drivers who cause crashes in Australia, than THC.

Road safety should come first

The researchers of the Zero Tolerance Drug Driving Laws in Australia report stress that RBT transformed the once common practice of drink driving in this country into a “highly stigmatised criminal behaviour”, which led to marked safety improvements on the road.

Since random breath testing was introduced in 1982, the number of fatal crashes that have involved alcohol in Australia has dropped from 40 to 15 percent. However, at present, there’s no accurate way to gauge the real impact that roadside drug testing is having on road safety in its present form.

“This seems to be a law based upon morality, as opposed to science and evidence,” Ms Faehrmann concluded. “Members of the community are feeling unfairly targeted over their lifestyles choices by the government’s zero tolerance agenda, as opposed to keeping people safe on the roads.”

Going to court for a traffic offence?

If you are going to court for a traffic offence, call or email Sydney Criminal Lawyers anytime to arrange a free first consultation with an experienced, specialist traffic lawyer who will accurately advise you of your options, the best way forward, and fight for the optimal outcome in your specific situation.