Police Should Test for Impairment Levels of Drugs, Not Minute Traces

On the first weekend of this month, NSW police carried out a roadside alcohol and drug driving blitz in the Northern Rivers region. And while locals aren’t complaining about officers booking drunk drivers, they are opposed to those charged with drug driving as there’s no proof they were impaired.

Those living in the northern coastal region are no strangers to this kind of police attention. Last year, there was a significant rise in highway patrol activity and with it came an increase in roadside drug testing, which in no way gives any indication if a driver is intoxicated at the time its carried out.

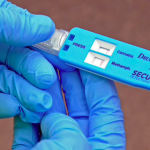

Unlike random breath testing (RBT) for alcohol, which measures levels of alcohol in the blood that have been scientifically proven to impair driving, roadside drug testing detects the mere presence of a few select substances in salvia, meaning the drug could have been consumed days prior.

So, in heavily targeted areas – like Nimbin – hundreds have been complaining that they’ve tested positive for cannabis, whilst not being under its influence. And for years, this has left the courts clogged with individuals who wouldn’t have been arrested if officers tested for impairment.

Bearing the brunt

“It’s really sad for everyone,” said Australian HEMP Party and Nimbin HEMP Embassy president Michael Balderstone, “because we yelled about medicinal cannabis for four or five decades, finally they accept it’s real, and then we just get hammered.”

Balderstone has long been a critic of police mobile drug testing (MDT) operations that were first introduced in 2007. And he’s witnessed the impact it’s had on Nimbin, which has been a flashpoint for MDT, even before the government announced it was tripling testing in December 2015.

“A lot of people have been losing their licences,” Balderstone told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “A lot of people have lost their jobs because they can’t get to work, because they can’t drive.” Indeed, in regional areas the loss of a licence can put a halt to employment and educational opportunities.

“There’s a lot of anger, because it’s so unfair,” the cannabis activist added. “The problem is pot stays in your system so long.” Not only have locals complained about testing devices picking up a joint smoked days prior, but also that the legal use of hemp oil has resulted in a positive reading.

The gold standard

Section 110 of the Road Transport Act 2013 stipulates that it’s an offence for a fully licenced driver to have a blood alcohol concentration that exceeds 0.05. And since RBT was introduced in 1982, the number of fatal crashes that have involved alcohol has dropped from 40 to 15 percent.

As the researchers of the Zero Tolerance Drug Driving Laws in Australia report explained, RBT transformed the once common practice of drink driving in this country into a “highly stigmatised criminal behaviour”, which led to marked safety improvements on the road.

Clayton’s road safety

But, this isn’t the case with trace-based roadside drug testing. Section 111 of the Road Transport Act provides that it’s an offence to drive with the mere presence of a prescribed illicit drug in a person’s oral fluid, blood or urine.

And these prescribed illicit substances are limited to amphetamines, MDMA, cocaine and THC: the psychoactive component of cannabis. Cocaine was only added to the list in July last year, following calls for this drug of the rich to be included with those used by the not so affluent already tested for.

Despite benzodiazepines being found in the blood of more drivers who cause crashes than THC, they and other prescription drugs are not tested for. And nor are the at least a dozen other illicit substances that Tasmanian police manages to pick up on using its roadside drug testing devices.

“I don’t think it’s anything to do with car accidents. It’s very little to do with impairment,” Mr Balderstone made clear. “It just infuriates everyone that you can drive with any mixture of pharmaceuticals and not get tested: opiates, methadone, etc.”

Judicial misgivings

Back in February 2016, NSW Greens MLC David Shoebridge spent a day at Lismore Local Court, where he found that 46 of the cases – or a third of the day’s hearings – were drug driving matters. And he related that police didn’t “put forward a shred of evidence” that any driver was impaired.

And earlier that same month, Lismore Magistrate David Heilpern ruled that Joseph Carrall was not guilty of drug driving, as it was found he hadn’t smoked any cannabis for nine days prior to testing positive.

A veteran of drug driving cases, Magistrate Heilpern remarked during another case in March that year that he doubted the NSW government’s claim that cannabis only remains in a person’s system for 12 hours. “In the vast majority of cases, the time frame has been over 12 hours,” he said.

But, despite the widespread criticism of this state’s roadside drug testing regime, NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian announced further investment in January last year, as roadside testing was to be doubled to 200,000 tests annually by 2020.

Drug impairment level testing is possible

What NSW citizens who’ve been following this matter want is for the government to implement a regime that tests for levels of drugs in a person’s system that have been scientifically proven to hinder driving.

And this is exactly what the Norwegian government did back in February 2012, when it rolled out a system that tests drivers for a whole range of non-alcohol drugs, including impairment levels of the four substances that NSW police are merely testing for traces of.

Norwegian police are testing for a total of 20 licit and illicit substances, including a number of prescription drugs, like benzodiazepines and methadone. Drivers are therefore deterred from getting behind the wheel while under the influence, as drivers in Australia are after drinking.

A complete overhaul is needed

Mr Balderstone said that there’s no way this state can have a decent medicinal cannabis program if the police are going to continue to test drivers for mere traces of THC, with no way to gauge if a person had taken their medicine or they’ve just smoked a joint before driving.

Medicinal cannabis is now legal and readily accessible in 33 US states. And it’s been shown that following the availability of cannabis medicines in these jurisdictions overall traffic fatalities have dropped by 11 percent. And in certain states the drop has been more pronounced.

“There needs to be a parliamentary inquiry. It comes from parliament and it has to go back there,” Mr Balderstone concluded. “I simply don’t think they know what they’re doing. I mean, I hope they don’t know what they’re doing.”

Going to court for a traffic offence?

If you are going to court for a traffic offence, call or email Sydney Criminal Lawyers anytime to arrange a free first consultation with an experienced, specialist traffic lawyer who will accurately advise you of your options, the best way forward, and fight for the optimal outcome in your specific situation.