Colombia Is Leading Progressive Drug Law Reform: Interview with Greens MLC Cate Faehrmann

Speaking at a recent cannabis symposium at Sydney University, NSW Greens MLC Cate Faehrmann told the crowd that she’d attended the 2025 Harm Reduction International Conference held in Bogota, Colombia, and the proposals being tossed about at that forum pretty much blew those comprising the NSW reform campaign out the water, in terms of how far their ideas have progressed.

For a country like Colombia, the chief global supplier of the internationally illegal drug cocaine, prohibition is increasingly considered an existential threat, and as Faehrmann explained in late November, this is why Colombian politicians, including senior ministers, are now seriously considering trialling legalised and regulated cocaine that would extend beyond its borders.

In coming from Sydney, Faehrmann found that many of the local participants from the conference were interested in speaking with her, as the city from which she hails, is understood to be a major destination on the global cocaine smuggling route, as the market is sizeable and the profits to be made on imported illicit substances in this country are ridiculously high.

Local NSW drug law reformists are currently down but not out, as the Minns Labor government took its preelection drug law reform stance and bastardised it and the momentum building around it, and following the official drug summit that it had to be dragged kicking and screaming to put on late last year, the state then took the most substantive drug reform recommendations and shot them down.

So, whilst premier Chris Minns, his ultraconservative police and health ministers and their Murdoch press hounders are satisfied with having killed off any chance for meaningful drug law reform for the time being, Colombia moved a resolution at the March 2025 meeting of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs, which has successfully led to a review of the three major drug control treaties.

The legal framework that imposes and governs the global drug prohibition regime has been created by the 1961 United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs and the other two later treaties that built upon its foundation were the 1971 UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances and the 1988 UN Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Cate Faehrmann, the NSW Greens drug law reform spokesperson, about how Colombia’s progressive drug law reform ideas could benefit us, and also how Australia could benefit Colombia via such law change, along with the benefits that could stem from overhauling drug control treaties and taking responsibility for harms caused elsewhere by local use.

Cate, you attended the Harm Reduction International Conference in Bogota Colombia 2025, which took place over 27 to 31 April, as you’d been asked to chair one of its sessions.

So, what was it like to attend such an event in Colombia, which is a nation that has been heavily impacted by the drug war?

Being in Colombia was incredibly powerful. This is a country that is on the front lines of the war on drugs and has paid an enormous price for our insatiable desire for drugs, like cocaine, particularly in the United States, Europe and Australia.

My first Harm Reduction International Conference was in Portugal in 2019, where the personal use of drugs has been decriminalised since 2001. This was groundbreaking at the time and Portugal still leads the way in terms of harm reduction.

This year, the conference in Bogota which was very apt considering the Colombian president has publicly advocated for a regulated cocaine market, including saying publicly that ‘cocaine is illegal because it is made in Latin America, not because it is worse than whisky’.

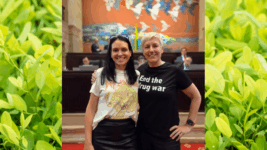

While I was there, I met with members of the Colombian parliament and also chaired a session at the conference about building support and coalitions for drug law reform.

Whilst at the forum you met Colombian MP María del Mar Pizarro, who is a keen drug law reform advocate like yourself. She told you about her legislation that proposes to legalise and regulate cocaine in Colombia.

For some in NSW, this proposal might sound a bit wild. Can you explain why it might not be such an out there proposal for people in Colombia? And why should such an idea not be so controversial here?

The insatiable demand for drugs, like cocaine, in many parts of the world, including Australia, has had devastating consequences for Colombia.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been killed, Indigenous peoples have been displaced, millions of hectares of the Amazon have been cleared and much more.

It’s estimated Colombia’s cocaine export generates an average annual revenue of $15.3 billion, but this money doesn’t go back to the local economy through formal jobs, taxes or contribute to the social safety net.

Many exploited coca leaf farmers earn just $1,000 a year on average, while this massive pool of money funds global criminal networks, and huge costs are borne by Colombia in security, public health and infrastructure delays.

Everybody I spoke to in Colombia knew that Australia was a big market for their cocaine, including Sydney.

The fact that cocaine is illegal hasn’t stopped demand for it growing year on year, nor stopped people paying astronomical amounts for a product that has been cut with potentially lethal substances.

Then there’s all the associated violence and killings on our streets as ganglords fight for control of the market.

Regulating a dangerous substance isn’t a new idea. Australia already does it with drugs like tobacco and alcohol and pharmaceuticals, so when you consider the lives that could be saved, and the fact that one of the source countries is pleading with nations to consider a regulated market to save thousands of lives, isn’t it worth the conversation?

But the ideas you were discussing with the experts in Colombia, including the justice minister, were much more advanced than what is up for debate and continually voted down by the majors on Macquarie Street.

At a recent cannabis symposium at Sydney University, you further outlined that those Colombian experts were interested in speaking to you about Sydney because it is such a significant destination for the global cocaine trade, and they even laid out some extremely progressive ideas in relation to this, can you speak on those?

I attended the meeting with low expectations, thinking I’d hear much of the same arguments in terms of the importance of criminalisation and targeting supply that we have come to expect back here in Australia.

Instead, the minister emphasised the importance of her government’s shift away from treating illicit drug use as a criminal issue to a health and social one, particularly in terms of human rights. Really, this is groundbreaking and from Colombia, no less.

A number of Colombian politicians, including president Gustavo Petro, have publicly stated their support for the establishment of a regulated cocaine supply.

This obviously is not an insignificant challenge, which, firstly would need to be done with some kind of cooperation from the drug cartels themselves, and secondly would need to be supported by progressive jurisdictions from a consumer country.

The mayor of Amsterdam has called for cocaine in that city to be regulated for example. Like Sydney, Amsterdam is seeing an increase year on year in cocaine consumption and supply, so they’re thinking outside the box about ways to reduce harm and stop the flow of billions to criminal drug syndicates.

It’s not just cocaine when it comes to Colombia doing better than Australia, particularly New South Wales, when it comes to harm reduction.

In Bogota, I also toured cannabis clubs which have been legal in the country for decades and spoke with frontline workers running drug checking services.

While you were at the harm reduction conference, you had discussions that involved the 68th session of the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs in March this year having adopted a resolution (E/CN.7/2025/L.6/Rev.1) put by Colombia that has led to a review of the international drug controls treaties with a view to modernising them.

You consider this a surprising and hopeful development. Why would an overhaul of these treaties be favourable?

The current international drug treaties oblige governments to criminalise possession and supply, restrict therapeutic research and place the UN’s enforcement bodies at the centre of decision-making.

The result has been catastrophic, with mass incarceration, entrenched violence in producer countries and a thriving criminal market, without making drugs less available or safer. In fact, they’re more dangerous.

At the 68th UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) held in Vienna in March this year, Colombia drove a genuinely historic development when countries adopted a resolution to establish a multidisciplinary expert panel to review all three treaties and make “clear, specific and actionable” recommendations to strengthen implementation and respond to emerging drug-related trends and challenges.

The panel is required to represent diverse expertise and policy approaches, and must consult widely with civil society, scientists, youth and other stakeholders. Progress on this process will be presented at the 69th and 70th sessions of the CND, in 2026 and 2027.

This is a huge opportunity for Australia, along with all those who have been working to reform drug laws, and I urge everyone to get involved in this.

For the first time, the system itself has admitted it needs reform. A modernised treaty framework could enable countries to treat drug use as a health issue, support evidence-based harm reduction, and allow regulated models that undercut organised crime.

With the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights last year calling for an end to the war on drugs, and the regulation of all drugs, I’m more hopeful than ever that we could be seeing the beginning of the end of the war on drugs.

Really, the only way I see us getting any significant shift in drug policy in Australia is after it happens at the global level.

Cate, you consider that Australia is quite removed from what is actually taking place on the global stage in terms of drug policy, even though the city of Sydney is a globally significant destination for cocaine smugglers.

So, having recently been exposed to this more advanced approach to getting out of the quagmire that is the drug war, what are the prospects in this regard when looking through this broader lens, and how might pulling some of those major party dinosaurs out of their hole to see the light be achieved?

In recent years, while public opinion has begun to rapidly shift, governments and conservative media continue to dig in their heels on the tough on drugs and ‘Just Say No’ approach.

But this narrative doesn’t ring true to the millions of us who have used some form of illicit drug safely, and to those who have experienced or witnessed greater harm caused by prohibition than the drug itself.

Meanwhile, our obsession in this state is with catching someone in possession of drugs for personal use, which sees billions spent on law enforcement while people have to wait months to access treatment if they need it. In fact, many people never get the treatment they need.

Hearing what’s at stake in Colombia firsthand, which is the epicentre of the drug war, highlighted how self-serving our arcane drug laws really are.

They exist to suit the political agenda and narrative of the political elite, and it doesn’t matter who is hurt or killed along the way.

This sounds extreme, but when people who have literally had members of their family killed because cocaine is illegal say that only a regulated market will break the cycle of violence, you realise it isn’t.

They’ve got actual skin in the game, and this is what they’re imploring the world to do. It’s time we started listening and working with them to end the drug war that has literally killed millions of people.