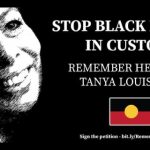

Failure to Press Criminal Charges over Tanya Day’s Custody Death Reflects Wider Injustice for First Nations

The decision not to charge two Victoria police officers that the state coroner suggested could potentially be found criminally negligent in relation to the ultimately fatal treatment that Tanya Day received whilst being held in police custody has left a bitter taste in the mouth of many.

None more so than the family the 55-year-old Yorta Yorta woman left behind.

Victoria police told The Age on 26 August that “after an assessment of the evidence and receiving advice” from the Victorian Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), it would not be pressing charges against the two officers involved.

It’s “extremely raw that Danny Wolters and Edwina Neale receive no punishment at all for taking our mother away from us”, Aunty Tanya’s daughter Apryl Day tweeted following the announcement. She added that Victoria police and the DPP “make a mockery of the ‘justice’ system”.

In a joint statement Ms Day’s four children have suggested that the DPP had decided to let the officers off in relation to having left their mother to “die on the floor of a police cell” based on a “flawed” investigation that “lacked independence”.

The Day family criticised the authorities for coming to the decision with no consultation with them or the broader Aboriginal community and they indicated further that the one chance over the last 30 years to bring about justice in an Aboriginal death in custody case has been missed.

A prejudicial system

Tanya Day died in hospital on 22 December 2017 from a brain haemorrhage caused by several falls she sustained within the first hour of being placed in a cell at Castlemaine police station. After suffering these injuries, she was then left lying on the floor of the cell for three more hours.

Prior to being taken to the lockup on 5 December, a conductor had woken Aunty Tanya on a train bound for Melbourne asking for her ticket. Having been drinking that day, the disoriented woman couldn’t find it, so the conductor decided to call the police.

This led to her being placed in a cell, under the watch of sergeant Edwina Neale and leading senior constable Danny Wolters. And after four hours of neglecting to follow cell monitoring protocols correctly, the officers realised Ms Day was in need of urgent medical treatment.

One of the reasons that police took Aunty Tanya into custody is that Victoria still has harmful public drunkenness laws on the books. And another reason, as pointed out by her children, is the systemic racism shown in enforcing these laws.

Hope dashed

The coronial inquest into the death of Tanya Day was significant not just in terms of its outcomes, but also in the fact that Victoria state coroner Caitlan English agreed to consider the role that systemic racism had played.

On delivering her findings last April, English noted that “Ms Day’s death was clearly preventable had she not been arrested and taken into custody”. She further outlined that “an indictable offence may have been committed” and recommended the DPP consider charges.

The Victorian coroner based these conclusions on evidence that revealed the officers on duty had failed to carry out proper cell checks in relation to a woman who was clearly in distress. This left Ms Day’s condition to deteriorate, when it could have been treated at an earlier stage.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Aunty Tanya’s oldest daughter Belinda Day following the coronial recommendations. She said that the coroner having made the referral showed clearly that her mother’s “health and wellbeing weren’t looked after”.

Despite over 430 First Nations deaths in custody since the 1991 Royal Commission into the matter, it’s very rare for a coroner to make a recommendation to consider charges. And over that time period, not one police officer or prison guard has been convicted in relation to any of these deaths.

Public drunkenness remains

Another unprecedented decision on the part of the coroner was that she stated prior to the inquest, that she’d be recommending the offence of public drunkenness be abolished. And the Victorian government announced in August last year that it would be moving to do this.

Belinda explained that this was a recommendation made by the Royal Commission. And she said, “Had the Victorian government actually heeded those recommendations and implemented it many years ago, it’s quite likely mum would still be with us today”.

It’s well known public drunkenness laws disproportionately affect First Nations people. At the time that Aunty Tanya was arrested, Aboriginal women were over 10 times more likely to be targeted by Victoria police for being drunk in public compared with non-Indigenous women.

Not only has Victoria remained one of just two jurisdictions – the other being Queensland – that has left this law on the books, but the penalty that applies to the offence has been increased eightfold since the turn of the century.

However, a year after the Andrews government made the promise to revoke this racist law, it still stands under section 13 of the Summary Offences Act 1966 (VIC).

The subtle indication

The decision to simply dismiss the recommendations of the coroner has dashed a lot of people’s hope in seeing the Australian criminal justice system actually bring about any substantial justice in terms of Aboriginal deaths in custody.

This dashing of hope comes on the back of a nationwide Black Lives Matter outcry over the prejudicial treatment that First Nations people have always faced at the hands of the imported justice system that deals with them as if they’re a problem on their own lands.

Over recent months, NSW Stop Deaths in Custody activists have called out their state coroner for simply dismissing custody deaths as accidents that don’t warrant any recommendations.

However, in Victoria, it seems that when the coroner does step up, those next in line ensure failure.

And as long as those charged with the power to hold those involved with First Nations custody deaths to account continue to refuse to do so, it simply indicates to those with the power to save these lives to throw the rule book out the window, as there doesn’t seem to be a problem.