Guilty of Refusing to Disclose Password: Wage Peace’s Margaret Pestorius on Eroding Rights

Police asking civilians for the passwords to access their mobiles has become the norm, but in the vast majority of cases in NSW and in Queensland, officers need a warrant or a court order to require the code to access a person’s electronic device, and that’s exactly what Queensland police did have included on the warrant when they raided activist Margaret Pestorius and she refused produce it.

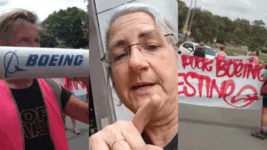

The Queensland Police Service Counterterrorism Investigation Unit executed five search warrants across Magandjin-Brisbane on 23 January 2024: one of which was at Pestorius’ home. These were in relation to two antigenocide protests that month: one that targeted a Ferra Engineering factory and a second had occurred in the reception of the Boeing Brisbane offices on 17 January 2024.

Pestorius, an activist educator for Wage Peace, was being raided primarily in relation to her part in the 17 January action at the Boeing offices, as she was later charged and then convicted over common assault, which she’s repeatedly explained amounted to her shoulder brushing past that of a Boeing employee as she moved through a doorway into the reception area.

Not guilty was how Pestorius pleaded on 6 July 2025 to a charge of not following an order to provide access to a device that is mentioned in a search warrant, contrary to section 154 of the Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000 (Qld). This offence carries up to 5 years inside. However, the magistrate didn’t agree with her, and the activist was given a 6 month suspended sentence.

Creeping criminalisation

As a self-representing defendant, Pestorius had put it to the court that the “violence” involved in her supposed assault and the impact she’d had on the Boeing office in general was of such a low-level that a search warrant was not justified and therefore, she should not have been compelled to hand over the password to her mobile phone to expose all her private information to the authorities.

But both the Boeing and Ferra actions were held against companies specifically over their supply of weapons or parts to Israel, which is perpetrating a genocide against the Palestinians of Gaza and the killing is spilling into the West Bank, and protest actions that have been supportive of the plight of the Palestinian people have increasingly been dealt the heavier hand of law enforcement.

So, while occupying workplaces and brushing against employees might be disruptive, the responses to these actions have been disproportionate, as early morning raids carried out upon nonviolent antigenocide agitators, who are then expected to hand over the code to their private lives, prior to being taken down to the copshop and being charged with overinflated crimes, is all a bit much.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Wage Peace activist educator Margaret Pestorius about Queensland gradually converting back to the attitudes of the criminal justice system of the 1970s and 80s that operated under then state premier Joe Bjelke-Petersen, and saw institutionalised corruption run rampant and major crackdowns on leftwing political-types and hippies.

Margaret, you appeared in court on 9 July 2025, on a charge relating to a Queensland police raid conducted on your Magandjin-Brisbane residence on 23 January 2024.

The raid itself was in relation to antigenocide demonstrations that you and others carried out at two premises in southeastern Queensland that same month.

You were then charged with the offence of refusing to provide access to information on digital devices during the execution of the search warrant, which is a crime that carries up to 5 years imprisonment.

You pleaded not guilty to the charge when you appeared in court this month, and a Queensland magistrate then sentenced you to 6 months prison time, which has been suspended.

So, what happened in court recently?

This is the standard sentence for this charge, whether you are dealing in child exploitation material or are part of a violent drug gang, which it was claimed this particular charge was made for, or whether you’re a nonviolent protester who’s involved in a network of people who have been involved in effective direct action.

Handing over the passwords was part of the warrant, and if you refuse to hand over your password, they consider you to be degrading the authority of the court as you are refusing a court-ordered warrant.

However, I pointed out that the warrant was, I considered, obtained under false pretences, in terms of the amount of violence I was involved in, which was raised in order to convince the magistrate in chambers that I was on a trajectory of violence and should be raided.

Is the “trajectory of violence” you’re on related to the assault charge you received after brushing past an employee, when walking through a door at the Boeing premises in January 2024?

Correct. I moved from 35 years of no violence at all, to lightly brushing past the arm of a Boeing employee while going through a door, so that is the trajectory of violence I am on.

At the Ferra Factory in January 2024, I was accused of being there, but at Boeing I was accused of assault, which involved lightly brushing past the arm of an employee, while taking a protest position at the door.

I put forth that I was involved in protected activity and that I had a duty under the Constitution to be raising issues, such as genocide, which I consider a very important issue during a genocide.

I also raised a defence using the Human Rights Act. I raised that I had the right to participate in political activity in this society even if it was at private places, and that I also had a right to keep my networks private.

Then I actually used another set of rights under the Human Rights Act, in regard to having the right to refuse the passwords because I had to keep databases safe and I’m regulated under social work arrangements to keep social work notes private.

I would say that under human rights law, I am required to keep my political networks private because that is freedom of association. Freedom of association is nothing if you cannot have privacy in your relationships.

The magistrate found me guilty regardless, stating that the fact that I had thrown my phone out the window showed otherwise.

So, more broadly what does it mean if a prominent figure in the antiwar movement is being dragged into court because they refuse to hand over their device passwords?

I said to the judge that it felt like we were re-entering the Bjelke-Petersen era due to the relationship we’re now seeing between the magistrates and the police.

That’s the point where the magistrates start serving the police and stop serving individual and collective civil liberties. So, we’re moving back into alignment with the arrangements of the Bjelke-Petersen days.

Under Bjelke-Petersen, there was a police complaints tribunal that was overseen by magistrates, and it never once found a police officer guilty in its whole 20 years. This was prior to the Fitzgerald inquiry, when they found that everybody was guilty.

But what we had under Bjelke-Petersen was magistrates refusing to use their intellectual rigour to separate civil liberties issues from criminal issues.

What the police do is they criminalise ordinary conduct. When people start rising up and calling out genocide by whatever means that normal people have to do that – by meeting, talking about it, speaking out about it, organising assemblies and different types of events – the police then find ways of criminalising those types of events, and the magistrates then go along with that shift.

So, you’re saying the police start acting like certain types of behaviour that weren’t criminal suddenly are, like has been seen with people protesting for Palestine?

The magistrates have an opportunity to say that it isn’t right, or that it is beaten up or this charge doesn’t fit that conduct.

Magistrates have this opportunity, but often they don’t exercise that power and they become subservient to the police prosecution, and they then become a police court.

So, the magistrates court in Queensland is a police court?

Well, I would say it is heading that way. There is no compulsion for them to act distinctly from the police.

Lawyers are well aware of this, and it’s just when an outsider, like myself, comes in and points it out that it receives attention. The lawyers say that is just how it is.

On 20 December, you were convicted on the offences that related to antigenocide demonstrations that resulted in the raid on your premises.

Following that court appearance, we discussed how the prosecutor had referred to you as a “fanatic” and concerns that this could mark the authorities attempting to frame you in such a manner in order to tarnish your reputation.

So, how did it go in court this time? Did the Crown attempt to frame your opposition to the war machine as some sort of mental issue?

My main defence this time was I had a reason not to hand over the password to my phone, which were certain private things: legal correspondence, social work notes, databases and general private activist conversations with large numbers of people.

The prosecutor spent 10 minutes explaining how discourteous, belligerent, angry and rude I was on the morning of the raid on 23 January.

I had to remind him that being discourteous is not an element of the offence, but it is something that they like to use to discredit your evidence to make you out to be very bad at the moment of arrest.

But the truth is during a raid you move between moments of lucidity and moments of being extremely angry about the intrusion, especially in the case when one feels entitled or justified to have been taking the conduct.

The conduct I took was to protest against a genocide and to organise against a genocide, when the World Court is saying there is a genocide.

So, you feel justified, and you feel furious that these people have intruded into your home and have started to move everything around and interfere with your organising capacity.

The prosecutor then translated this as me seeming to be very upset at one moment but then being able to think properly about this, this and this at the next moment. But the truth is, that is the human condition: one minute you’re lucid, the next minute you are disturbed, and the disturbance creates the lucidity of the next moment.

So, I did move between lucidity and fury when I was raided at 6.30 in the morning and I was seeing my friends detained in my apartment. That is why he made me out to be discourteous, belligerent, rude and unhelpful, all of which was true.

Queensland is one of the few states to have enshrined human rights in law. The Labor government notoriously suspended the Human Rights Act 2019 (QLD) twice, to pass youth crime laws that breached rights, and these days, the Crisafulli government is on a drive to lock up as many kids as he can in that state’s child prisons.

So, you’ve already touched upon it, but how would you say the state’s HRA is being applied in cases like your own?

The human rights law appears to be pretty much useless at this level. It appears to have a discursive influence on the incident at hand.

The magistrate refused to enter into rights arguments with me, as I was a self-representing defendant.

What I have heard from lawyers is that they don’t want to be involved in cases that result in negative case law, and that they want the perfect case, so they can run arguments that set positive case law.

But that abandons us as activists at the grassroots, and it actually abandons people, ordinary citizens.

And lastly, Margaret, given that we’re almost two years into the worst atrocity crime since World War II and there is only mounting talk of war on China and given also that the authorities are cracking down on antigenocide activists, what is a long-term antiwar demonstrator like yourself to do under these circumstances?

We have to organise. What organising means is bringing people into the movement and teaching them the skills of organising and teaching them new things quickly and then collaborating and organising large cooperative events that put a stick in the spokes of injustice. That is what organising means.

We need to keep organising and organise as collaboratively as possible to make bigger events using the power of the politics of nonviolence.