Providing a Future for NT Youth: An Interview with Bush Mob CEO Will MacGregor

Last week, the Northern Territory Supreme Court released Dylan Voller from prison, eight months early. Justice Barr released the 19-year-old Indigenous man, so he can undertake a sixteen week rehabilitation program at the Bush Mob facility in Alice Springs.

Mr Voller came to national attention last July, after the ABC Four Corners’ program Australia’s Shame exposed abuse that was being perpetrated on youth detainees held at Darwin’s Don Dale youth detention centre.

The young man – who was sentenced to three years and nine months in prison for aggravated robbery in 2014 – has spent little over a year and a half outside of detention since he was 12-years-old.

Systemic Abuse in the NT youth justice system

During that time, he has been the subject of multiple acts of assault and what can only be described as torture at the hands of youth justice officers, including an occasion in 2015 where he was strapped to a chair and hooded for two hours.

Reports of abuse at the Don Dale facility first came to light in August 2014, when six youths –including Voller – were tear-gassed in cells of the centre’s isolation wing, known as the Behavioural Management Unit.

Three weeks prior to the tear-gassing incident, five boys had escaped from the centre. When they were recaptured, they were placed in isolation for over two weeks. They were locked in their cells for almost 24 hours a day, with no running water or natural light.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein said he was “shocked” by footage of abuse at the centre. He remarked that the incidents may have contravened the UN Convention for the Rights of the Child and also the Convention Against Torture.

The Royal Commission

The publicity surrounding the treatment of Dylan Voller and other youth detainees at Don Dale led to the establishment of the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory.

The Commission is currently underway, having just received a four month extension, and its final report will be table on August 1 this year.

Antoinette Carroll, youth justice advocacy project coordinator at the Central Australian Legal Aid Service, told the Commission that Mr Voller was “set up to fail” by the system from the beginning.

Bush Mob providing a brighter future

But Dylan now stands a better chance. As of Monday, he’s been at the Bush Mob Aboriginal Corporation’s rehabilitation facility in Alice Springs. The 20 bed centre provides a therapeutic program for young people – between the ages of 12 and 25 – who have issues with drugs and alcohol, or are caught up in the youth justice system.

Youths at risk are referred to Bush Mob and they’re provided with a structured program, which helps them to make positive choices for their future. While it costs around $677 a day to detain a young person in youth detention, it only costs $350 a day for them to undertake the program.

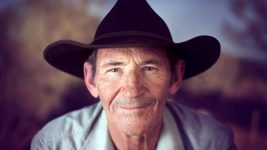

Established in 1999, Bush Mob is run by Will MacGregor a former NT ranger, who has a strong interest in the work of traditional Aboriginal healers. He received the Australian of the Year Northern Territory award last year, for the work he does at the centre.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke with the chief executive of Bush Mob Will MacGregor about the issues being faced in the youth justice system and the vital work his organisation is providing to marginalised youth.

The Northern Territory youth justice system has come under huge criticism since it came to light in July last year that children were being tear-gassed and tortured at Don Dale youth detention centre.

How would you describe the state of the Territory system?

I’d suggest that the youth justice system across Australia is broken, in light of the stuff in NSW and Queensland. And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

The state of the system is that people are desperately trying to review, move on and change. But behind all that, most governments haven’t sorted out what the response to young people should be. Nobody is having the conversation, the collaboration – it should be across Australia, not just NT and SA.

There should be conversations happening at a national policy level and then down, including young people. Because they seem to get left out of the equation in discussing what’s good for them.

Do you think there’s too much of a focus on punitive measures within the youth justice system?

Yeah. I actually think: What is punishment? As in, our society needs to revisit that and have the discussions. The last youth policy of the Commonwealth was under Rudd. And primarily it was mainstream young people that were asked to speak at the formulation of that policy.

If I’m a young person and I’ve had a rough time and I’m in a gang, or whatever I am – or I have lots of interaction with the criminal justice system – I have equal leadership skills in my own way. All that needs to happen is a forum, where I can actually be positive, rather than the negative.

Besides Bush Mob, what other government-funded support and rehabilitation services are available for marginalised and disengaged youth in the Territory today?

There’s us here in Alice. I’m talking about drug and alcohol. We’re sort of a quasi-bail option as well. There’s an organisation called CAPS in Darwin. There’s a private one called Brahminy, which is a business model. And there’s Mount Theo in Warlpiri triangle. That’s it.

The other side of that is we get weekly requests from interstate for placements. We’re funded by the NT and Commonwealth. So our placements are primarily for NT young people. But we get young people, mums, dads, agencies from every state and territory requesting placements here. Because there doesn’t seem to be similar sorts of programs where they are.

We’re actually allowed by NT Health to take a couple of placements at a time, provided the agency that refers them pays.

It should be going back to the whole of the country. There should be some sort of collaboration capacity to exchange and also build on other programs in other states and territories, so that there’s something being done at the pointy end.

There’s limited placements from NT. We’ve got twenty beds in Alice Springs, and we’ve got ten beds for a pilot program at Loves Creek Station that has been funded one lot of six months, and now a second lot of six months. That’s it for our beds – thirty beds.

Bush Mob Aboriginal Corporation provides residential rehabilitation programs for youth between the ages of 12 and 25. How does Bush Mob’s program and centre differ from what else is available out there for youth at risk?

What we tried to do in the beginning was listen to what local people wanted for their young people. And sit that in a western top-down funding model. So you can imagine the western top-down funding model is quite rigid. But what we do is bend the parameters as far as possible, without breaking them.

It goes back to listening to elders, community groups and public servants that support us in principle, but won’t do it publicly. Listening to people and going, “OK, we’ve got this place. This is what we think should happen, while they’re there.” And trying to take that on board and match it against what the government requires for the funding.

One of the reasons is there’s always been community oversight around our stuff. We’re not some tucked away clinical service attached to a hospital. We’ve actually got really strong boards of management, or directors, who are a good match for our local region. They keep an eye on things.

There’s other people in the community that come back and forward. And if they think we’re doing the wrong thing, they tell us. And we encourage that.

So I think a plus is there’s some sort of community ownership. And the other thing is there is ownership by the young people. We try to build ownership with the young people that use our program, or are directed here.

And one way we do that is say, “Regardless of being a bail option, do you want to come here? Because if don’t, you’re just going to bolt.”

It’s giving them back choice, even though, it’s limited choice. If anyone gets control in the decision around them, they feel better. It’s going, “Hi, how are you? Who are you? What do you want?” Part of it is you being sentenced here, or ordered here. The other bit is, “We’ll try to deal with some of those issues, if you want. And what do you think about it?”

Bush Mob provides a therapeutic service, which helps young people in making positive life choices. How do you go about doing this?

Basically, we’re looking at what’s surrounding that young person coming in: clothing, shelter, sleeping safely, try to get over trauma from physical and emotional abuse, a medical check. So, where are you at? Like a tune up, when you go to the mechanic.

Behind all that is a structure, as in a structured day. You get up, you clean your room, you have a shower, you have breakfast and you go to school, if you’re school age. If you’re not school age, you start looking for work, and training. When you get back from school, there will be swimming. If you play sport, you go and play it. So try to normalise what’s happened.

Going on from there, we offer counselling. And a lot of people go, “No way. I’m not talking to anyone.” There’s a professional stream. And then there’s a narrative stream, as in, workers talking to you. “How you going? How was school? What’s happening? How’s family?” So that needs to happen.

And we talk about restorative stuff, like, “OK, you stole a car. What do you think about that?”

“Oh, who gives a fuck?”

Then in a couple of weeks, “You stole a car. What do you think about that? And what if someone stole your hat, or you headphones?”

“Oh, I’d be pissed off.” You know, beginning to go, this is what it’s like, when you commit a crime. “And how do you think victims feel?”

In the beginning, “Who cares?” Mid-way, towards the end, a lot of young people start going, “Oh, OK, regardless of the circumstances that drove me to that, whether it was peer group pressure, or I was hungry, or whatever it was. I can actually see that there’s an impact on a victim. And by being here and participating, I’m trying to make that change.”

I’ve always been fully in favour of Koori Courts. But there’s not enough, and there’s not enough funding, and there’s not enough impetus that way.

The other thing is, “Well, what do you want to do in the future?” We can’t change the landscape out there. We can’t change what happens in a remote community in Arnhem Land, or central Australia or the Barkly Region.

But what we can say is, “If you’ve done sixteen weeks here, it’s like a bankable bit of time that you can take away with you. The same as the fond memories you have of your grandma, your granddad, or your aunty. And then, if you’re going to do something crazy, it might help you to think about not doing it.”

It’s pretty simplistic. It’s like talking. It’s like, “Who are you? How are you? What’s happening?” It’s really simple. It’s not rocket science. You don’t have to jump through hoops. You have to just be around normal humans in a group for sixteen weeks. This is all we can afford.

We’ve built in multiple entry and exit. Because we’ve got a huge age range: 12 to 25. So I might come here at 12. I might come back here at 16. I might come back at 17. Twelve to 25 is a massive developmental range, so you’re looking at late childhood, early adolescence, adolescence, late adolescence, young adult, adult.

Young people are meant to be taking risks. They’re meant to be doing stupid things – we all did. You did. I did. But it’s what surrounds them that helps them think about those things.

So part of our stuff is we do bush trips regularly. Today, they’re going swimming in a waterhole. On the weekend, they do stuff. Whatever the community stuff is. There’s rugby league this weekend. So they’re going to go watch that. The Titans versus someone else.

It’s just trying to normalise what’s been happening.

Our belief has always been, any work in this area needs to be long-term and intergenerational. Our governments don’t do that. They’re short-term consumerist governments. In terms of bipartisanship around anything, it only lasts for four years. And then a new mob comes in and everyone has to reinvent the wheel.

You either get defunded, or you reinvent yourself, so that you can sell it to the next minister. Whereas, the reality is that we’ve got three generations at least that are out there with limited futures. And in the meantime, there’s nothing happening around work for young people – proper work – or the opportunity to have a chance.

“What’s happening with school? Why aren’t you going to school?”

“Because my clothes are dirty and I feel ashamed.” Or, “There was fighting in the house last night. I’m tired. I can’t keep awake.”

Those things need to be addressed.

The school that’s on offer for young people here are flexible learning centres. They aren’t mainstream school. And that’s where we can send young people to start reengaging with education. And they’re a wonderful place, but again, they’re not adequately funded.

The question is: If you’ve reengaged with some form of school, while you’re here, what happens when you go home? Because is the department interested in you?

There’s a whole range of things that we can’t do when a young person leaves here. We’ve got Facebook. We follow up with phone calls. We do all that. But hey, it’s a big bad world out there, because there’s no direction around the whole youth thing.

And then behind that, there’s the hysteria around whatever the new drug is – ice, or whatever. Which is not around measured, structured interventions.

We get ice kids here from Darwin and Palmerston quite often. But we’re not set up for that type of drug. And we’re not funded for that sort of drug. And then next week, it will be something else.

There’s a tendency of media to focus on whether it was ecstasy or whatever it is, when people die. Rather than look at the long-term intergenerational viewpoint around any of these issues.

So you’re centre mainly deals with Indigenous youth?

We take all young people. And that’s from forever. We’ve been around 18 years now.

But, the point is that the numbers of Indigenous young people that we receive in our place, highlights what’s happening in our society. We have pretty much 98 percent Indigenous people, and 2 percent other. Because they’re the people that are being affected by lack of appropriate policy across our nation.

Not because they’re bad people. It’s a reflection of statistics and lack of policy from government.

From day one, we’ve always had any young person. So the percent of white fellas or other has been 5, 2, 3.

Bush Mob was established 18 years ago. What sort of outcomes has your program provided?

OK people talk about outcomes, one view of that is you’re a druggy, or whatever you are, you go into a treatment program, and you come out cured. But that’s not true. Particularly, in light of the vast developmental range of the young people that come here: 12 to 25.

What you do is possibly improve. You might moderate. You might change.

Our outcomes have been, yes, young people have reengaged with school. They’ve completed the whole time that they’ve meant to be here, instead of buggering off. They’ve learnt about strategies to deal with, “Oh I might pick up again” – relaxed prevention. They may have reengaged with education. They may have reengaged with family. They may have reengaged with the community.

On top of that, you may get young people who go from here and work. Or actually, go back into mainstream school.

We’ve also had a program here, where young people who are 18 and above that have been through our programs over the years, often ask us for work. Over the 18 years, there’s been about 59 that have been employed.

Currently, there’s four onsite. We don’t get any support for that. And the way that we can do it is that we put them on a casual basis, employed the same as any other worker. Whatever training is happening, they’ll do it at the level that they want to do, and feel comfortable with doing.

By being casual, if there’s a death in the family, if there’s a massive fight, or whatever’s happening, they tell us and they disappear to deal with those issues, and then return. So in their head they’re not breaking some sort of contractual agreement. And they don’t feel ashamed about it.

The other thing is that we, within our service, we work long-term with Indigenous people, and the thing is how to do it respectfully from the learning that we’ve had.

Our outcomes have been – going back to basics, because you’re looking at individuals here, not a group of alcoholics, or sniffers, or ice addicts – it’s an individual person coming in, so they might have sorted out their mental health issues, or started on the road to that.

They might have been suffering from schizophrenia and have finally got their blood levels checked, so that the medication regime is adjusted accordingly. Or they’re having their medication for the first time in five years. They’ve been referred to other psychologists, psychiatrists, doctors.

They’re actually on an electronic health record for the first time in a long time. They’ve sorted out Medicare.

We have a collaboration here where we have a doctor, a psychologist, and a psychiatrist, which we’re not funded for. It’s a voluntary partnership. Those people we give them space, as in an office. And they pay themselves through the consults through Medicare. There’s no money involved. We don’t have that money.

And behind them, we’re also supported by Aboriginal Medical Services.

I reckon they’re pretty good outcomes. Our numbers are about 180 to 200 individuals per annum in the town facility. We keep getting referrals. Most families are quite happy with what we’re doing, otherwise there would be no people coming here. And we wouldn’t want them coming here if they thought we were doing the wrong thing anyway.

And lastly, Bush Mob are providing a vital service to North Territory youth at risk. But your centre can only cater for so many people. What sort of institutional changes do you think need to happen in the Northern Territory to better provide assistance and help to marginalised youth?

I actually think, going back to question one, that there should be national collaboration around these issues, rather than single out any jurisdiction.

We’ve got the royal commission happening at the moment into juvenile detention. And apparently a minister is going to announce at one pm today that there’s more money coming into our side of things, diversion and other programs.

There’s been a lot of really good work done over the years by a lot of really good people. Many of those agencies have been defunded, maybe they’ll look at those.

My belief is rather than look at the discussions that are happening in the media and otherwise, which are polarising, which is normal in our day and age. We should look at proper collaboration around discussions of what we’re going to do.

And what our view of punishment is. There does need to be some sort of juvenile detention for offenders that have gone that far. But appropriately, have staff with all the training and the rest of it.

And a real good review of the thinking. I think the systems are broken, and I said that in the beginning. That’s not a criticism. What it is is OK let’s move forward from that. Let’s be positive and proactive.

Importantly, ask young people what they think.

Engage the people who it’s affecting.

Yes. I don’t mean just kids who have a roof and an ability, I mean everyone. I think it’s time for major changes across all sorts of areas in our society – education, the whole lot. What are we providing?

Will thank you very much for speaking with us today. And best of luck with the continued success with the program that you and the Bush Mob team are providing.

Thank you mate.