Rally Against Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, as NSW Reaches Deplorable Record

“As a Dunghutti man, I have lived the grief, anger and frustration that comes from seeing our people die in custody,” said Paul Silva, a prominent voice in the local campaign for First Nations justice. “Every death is a profound loss, not just for families, but for entire communities. These are not just statistics – they are our mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters and children.”

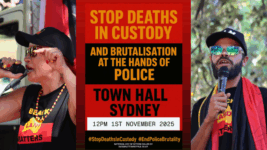

“Each death leaves a hole that can never be filled, a wound that keeps growing as we wait for justice and accountability that so often never comes,” the organiser of the 1 November 2025 Stop Deaths in Custody rally, which is set to take place on Gadigal land at Sydney Town Hall at 12 pm.

The rally calling for an end to deaths in custody is being held at a vital moment, as NSW state coroner Teresa O’Sullivan announced last week that this jurisdiction has reached a “profoundly distressing milestone”, which involves 12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people having died in custody, so far this year, which is the highest number ever recorded in a single year.

O’Sullivan further points out that the number of First Peoples in state prisons has risen by 19 percent over the last five years. There were 4,386 Indigenous inmates in NSW prisons in June this year, which accounted for 33 percent of the entire population, whereas Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people only account for 3.4 percent of the entire state populace.

As Aboriginal Legal Service chief executive Karly Warner outlined on the day of the announcement, the number of deaths should be sounding alarm bells, as “a prison sentence should not be a death sentence”. The palawa lawyer added these deaths are preventable and prison rates are their chief cause, as “NSW is driving more Aboriginal women, children and men into prison than ever before”.

“Too many of our people have been taken”

“My own family has felt this pain deeply,” Silva told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “My uncle, David Dungay Junior, was a proud Dunghutti man who died in custody in 2015 at Long Bay Goal. He was restrained and denied the care he needed, and despite our relentless fight for justice, the system has failed to hold anyone accountable for his death.”

“Coming to terms with the fact that there may never be justice for him has been one of the hardest hurdles of my life,” the protest organiser continued. “Yet, his story fuels my commitment to fight against the ongoing deaths of our people in custody.”

Silva added that he’s calling for a national day of action on 1 November, and there is a rally organised for the same day in Lismore, where participants will be meeting on Widjabul Wia-bal land at the local transit centre and then they will be marching to Lismore police station.

The Dunghutti man further makes clear that the mobilisations also have a focus on ending police brutality in this state. Silva asserts that too many First Nations people have had their lives brought to an end early, when being held in the custody of either Corrective Services NSW or the NSW Police Force, which has left too many families “grieving without justice”.

Paul’s uncle, David Dungay Junior, was killed by five speciality prison officers, when they held him down in the prone position on a prison bed because the 26-year-old man was a diabetic and he refused to stop eating some biscuits. The guards held him down as he cried out he could not breathe. At the end of the inquest, Corrective Services simply apologised for the “organisational failures”.

“A national crisis”

“This is not just a family issue – it is a national crisis, and everyone should be outraged,” explained Silva. “We cannot remain silent while Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continue to die in custody at rates far higher than the rest of the population.”

“These deaths are preventable, and the systemic failures that allow them to continue are unacceptable,” the protest organiser continued. “Families like mine are left to grieve while waiting for answers, often being ignored by the very system meant to protect us.”

The Australian government real-time deaths in custody dashboard states there have been 24 Aboriginal deaths in custody nationwide so far this year. The page further outlines that 609 First Peoples have died in the custody of Australian police and corrective systems since April 1991, when the Royal Commission into Deaths in Custody handed down its final report.

The dashboard was launched in mid-2023, as a way of “taking action to turn the tide on the appalling rates of incarceration and deaths of First Peoples” in custody. Yet, many have remarked more practical reforms might have been warranted.

The Royal Commission was convened in late 1987, as there was a crisis in deaths then, as now. The investigation provided a comprehensive list of 339 recommendations that sought to overhaul criminal justice systems in a robust manner, so that such deaths would be prevented on the ground, but further so less people would end up in a position to be able to die in custody.

The 87th recommendation is that police officers should “arrest people only when no other way exists for dealing with a problem,” while the 92nd stipulates that “imprisonment should be utilised only as a sanction of last resort.”

However, successive federal, state and territory governments have never attempted to implement these recommendations in full. A key example of this is that recommendation 165 calls for the removal of “hanging points in police and prison cells”. The Guardian reported mid-year this year that 64 deaths in Australian prisons over the last two decades were due to remaining hanging points.

“The time to act is now”

“We need urgent transparency, accountability and reform to ensure that no more lives are lost,” said Silva. “Everyone – community members, leaders and governments – must feel the outrage and demand action. We cannot wait for the next death to force change.”

Senator Lidia Thorpe has been consistently raising with the Albanese government that it could intervene in the states and territories to ensure that the Royal Commission recommendations are implemented. The Gunnai, Gunditjmara and Djab Wurrung politician has further backed peak body NATSILS in calling on Canberra to enforce minimum prison standards nationwide.

Since 2007, the federal government has also been running the Closing the Gap initiative, which includes as one of its key goals, reducing the disproportionate rates of Indigenous incarceration on this continent. However, close to two decades later, things are just getting worse.

“We must speak up, stand together and fight for justice,” Silva further maintained. “My uncle’s story is a stark reminder of the consequences of inaction, and it is why we cannot stop pushing for real reform. Our people deserve safety, dignity and the certainty that their lives matter.”

“The time to act is now, and we all have a responsibility to demand justice for every Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person who has been lost in custody,” the proud Dunghutti man concluded.