The Hypocrisy of Australian Politicians Condemning Crime and Corruption

On the day of the release of the Brereton report into alleged war crimes perpetrated by Australian SAS troops in Afghanistan, Independent federal MP Andrew Wilkie suggested in a tweet that the concern being shown by government ministers over its revelations was “hypocrisy on steroids”.

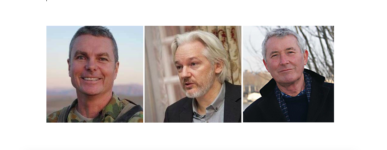

“They’re the very same people condemning the whistleblowers, lawyers and journalists revealing war crimes,” the politician continued, and went on to list the cases of Julian Assange, Witness K and Bernard Collaery, ADF lawyers and ABC journalists.

The result of a four year investigation, the Brereton report uncovered evidence of an alleged 39 murders of captured Afghan troops and unarmed civilians, and 36 matters have been handed to the Australian Federal Police, with a view to potential prosecutions in civilian criminal courts.

“Accountability will be the cornerstone of Defence’s response to the inquiry report,” defence minister Linda Reynolds said in statement. “I am profoundly conscious this process continues to be extremely challenging and distressing for many individuals and families impacted by the inquiry.”

However, as Wilkie points out, while ministers are busy addressing and acting upon what was revealed in the government-commissioned report, these same individuals are busily attempting to punish those who’ve exposed uncomfortable military truths via other means.

The Wikileaks founder

Julian Assange is currently being held on remand in London’s Belmarsh Prison, waiting for the determination on whether British authorities are going to hand him over to the United States to face multiple espionage charges carrying an accumulated sentence of up to 175 years.

The charges relate to conspiring, obtaining and disclosing defence information. But when it’s all boiled down, the real reason Washington is out to get Assange is because he published classified documents given to him by Chelsea Manning that exposed US war crimes in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The further travesty is that the United States has been able to reach out across borders and arrest the Townsville-born journalist, and now it’s attempting to extradite him under a treaty that specifically rules out extradition over charges that are political in nature.

Yet even though Assange is being subjected to this treatment for exposing war crimes – similar in manner to the Brereton report – our government has done next to nothing to assist him.

Other journalists – Peter Greste and James Ricketson – have been afforded special assistance, while Julian has been left to rot.

A duty of conscience

The starkest incongruity that the release of the Brereton report lays bare is the government’s decision to prosecute whistleblower David McBride for exposing the problems of the way special forces were operating on the ground in Afghanistan, following two tours as a military lawyer.

After trying for years to communicate his concerns internally within the Australia Defence Forces to no avail, McBride eventually passed on classified information to ABC journalists, who published the details as The Afghan Files. These documents contained at least 10 accounts of unlawful killings.

McBride is now facing five national security-related charges that carry the possibility of life imprisonment all for exposing the very same culture of coverups and war crimes that have just been brought to light.

And unlike the Brereton inquiry team, McBride has risked all in doing so.

Head of the inquiry NSW Supreme Court Justice Paul Brereton has called for no one who helped in revealing war crimes be prosecuted. However, the charges against McBride stand. His lawyer Mark Davis has described the continued prosecution as “unfathomable” in light of the report revelations.

Not in the public interest

In response to revealing the special forces “warrior culture” and alleged war crimes in The Afghan Files report, the AFP raided ABC offices in Sydney on 5 June last year. After scouring the broadcaster’s computer system, detectives left with two USB sticks containing files.

There were concerns that ABC journalist Dan Oakes might be prosecuted following the raid. But, last month, the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions said that while there was enough evidence to secure a conviction, it wasn’t in the public interest to pursue the matter.

This leads to the obvious question as to why it’s in the public interest to continue with the prosecution of McBride.

Independent senator Rex Patrick has remarked that the “persecution of whistleblowers is not in the public interest”, adding that “McBride is a hero”.

These circumstances mirror the decision of Washington to simply pursue Assange over the publication of US war crimes, while WikiLeaks’s media partners – the Guardian, New York Times, El Pais, Der Spiegel and Le Monde – have received no flack for printing the very same information.

A dwindling democracy

The government’s prosecution of one whistleblower for revealing what certainly is in the public interest, while turning its head away as some of its closest allies persecute a multi-awarding Australian journalist for doing the same, does seem to be part of an emerging pattern.

Despite 2013 AFP raids on the homes of former ASIS officer Witness K and lawyer Bernard Collaery over exposing the 2004 bugging of East Timorese government offices in Dili by our government, former attorney general George Brandis didn’t consent to their prosecution in September 2015.

Although, current attorney general Christian Porter decided to give approval to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions to go ahead with these proceedings in mid-2018. Porter did this within six months of taking office.

Witness K and Collaery are now facing closed court trials, as is McBride. The prosecution of these Australians for speaking truth to power is able to take place in secret as orders can be issued under the provisions of the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004 (Cth).

The NSI Act requires that the issuing of any NSI orders – that permit closed court proceedings – are published annually.

Over the years 2010-11 to 2017-18, no NSI orders were issued. However, over the last two financial years, four have been. And these were issued by current attorney general Christian Porter.