“The Majority of Strip Searches Are Illegal”: An Interview with Redfern Legal Centre’s Sam Lee

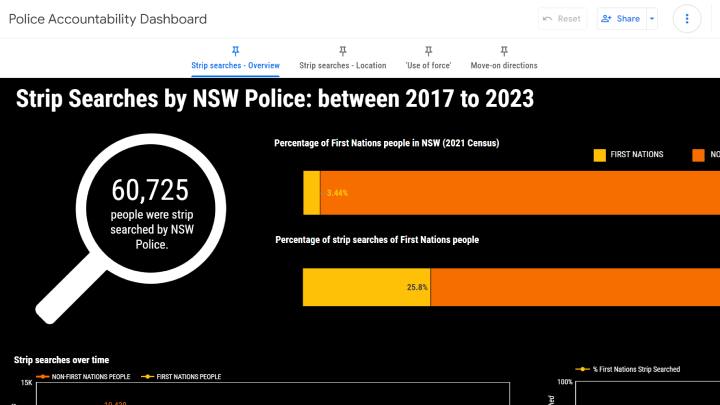

The NSW Police Force conducted 2,487 strip searches in the field across this state over the financial year 2022-23. And of these searches 13.8 percent were conducted upon First Nations people, despite the Indigenous community only accounting for 3.4 percent of the entire state populace.

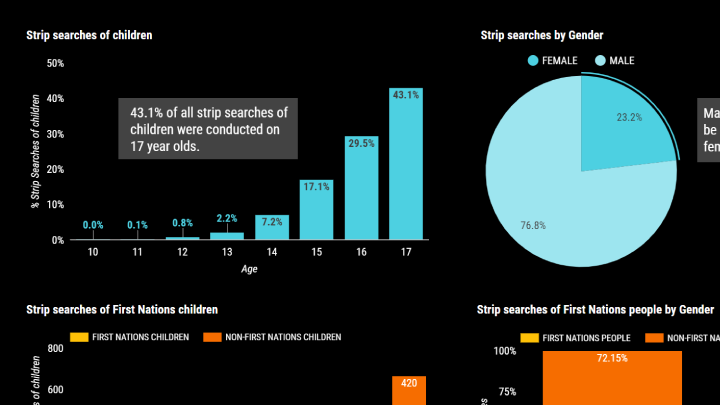

Over this time frame, NSW police officers found it necessary to strip search four 12-year-olds, six 13-year-olds, five 14-year-olds, eight 15-year-olds, fifteen 16-year-olds and nineteen 17-year-olds. And many of the older teens made to strip off in front of grown strangers would likely have been stopped and subjected to a search on their way into a music festival or an event.

Illegal items were found as a result of these strip searches on only 48.2 percent of occasions. And the most common items found were illegal drugs, which accounted for 912 of instances in which an illegal item was discovered.

A decade ago, this wasn’t the case, however, as while NSW police have long been able to strip search in relation to crime, in terms of the great numbers being strip searched following a drug dog indication and a pat down search that turns up nothing, this practice was first noted as being on the rise back in early 2015. And much of that increase involves their application at music festivals.

Police Accountability Dashboard

The reason these figures can be cited so precisely now is that the Redfern Legal Centre last week released its Police Accountability Dashboard, which contains the NSW police statistics regarding strip searches, use of force and move-on powers over the financial years 2017 through to 2023.

So, with the push of a few buttons one is able to see that over the financial year 2022-23, the area in which the most strip searches were conducted was Sydney Olympic Park with 265 strip searches performed, compared with 137 such searches carried out in Surry Hills in second place.

Redfern Legal Centre supervising police powers solicitor Samantha Lee explains that the way in which the dashboard is designed, it is able to tell compelling stories about how police powers had been utilised over those six years.

Indeed, the high number of strip searches at Sydney Olympic Park would suggest that people are being ordered to take their clothes off in front of officers, after a drug detection dog indicated them and an initial pat down search turned up no illegal drugs, as they were attempting to enter an event.

The largest class action against NSW police

In response to an onslaught of stories involving teenagers being illegally strip searched at music festivals by adult police officers, Redfern Legal Centre and Slater and Gordon announced that they were launching a strip search class action with the dual aim of seeking compensation and reform in 2020.

And despite the state of NSW attempting to shut down the class action, claiming there was no commonality between plaintiffs, the NSW Supreme Court ruled last December that it should go ahead, as it’s the most efficient and effective way to deal with this matter.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Samantha Lee, RLC’s senior police powers solicitor, about the transparency brought by the Police Accountability Dashboard, the fact that strip search use is rising again after a pandemic drop and how the process of changing NSW police culture is a long game.

Redfern Legal Centre launched its new Police Accountability Dashboard, which is a tool that makes comprehensive statistics around NSW police use of certain powers available to the public.

These powers are strip searches, use of force and move-on directions over the five years to 2023.

Sam, can you give us a more detailed explanation as to how the Police Accountability Dashboard works, the need for it, and why these specific powers are its focus?

It’s an accumulation of statistics that we have been gathering over a period of time. And these are issues that we have been looking at on a systemic level.

So, how it works is it has been inputted with data directly from NSW police, via access to information law, and people are able to drill down for certain stats. For example, with strip search statistics, they can drill down by location, age and gender.

And of particular note is the emphasis on showing through the dashboard, the disproportionate number of police powers used against First Nations people.

The dashboard is a way to tell a story around the statistics, particularly in regard to the policing of First Nations people in NSW.

In reference to the use of the new dashboard, you’ve said, “increased transparency around police powers leads to greater accountability in their use”. What are some of the key issues that the dashboard makes transparent?

I always work from the position that NSW police are a government body, and in that sense, they are accountable, as a government body, for their use of resources and how resources are used.

And I’m of the view that the dashboard does demonstrate to people how police powers are utilised, who they’re being utilised against, and transparency to me means accountability.

If you know where the powers are being used, then you can see through the dashboard, the potential that they’re being used against First Nations people but also people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds in NSW.

The figures cover the five years to 2023, which includes the pandemic period. And just prior to the onset of COVID, there had been a lot of focus on the police use of drug dogs and strip searches in public and then there was a lull in their use during the lockdowns.

What do these figures tell us about the use of strip searches since the lockdowns? Has the use of this invasive procedure picked up again in a similar manner to the way this was happening before the pandemic?

We certainly saw a decrease during the COVID lockdown periods, particularly because music festivals were shut down during that time.

Of note is that there was a consistent number of First Nations people strip searched during COVID – that didn’t seem to drop at all.

But we have seen an overall increase in strip searches again, as music festivals get off the ground, which is disappointing because we are trying to reduce the number of strip searches in the community.

We are of the view that the majority of strip searches are unlawful and continue to be unlawful because police are not meeting the very high legal threshold to conduct a strip search.

Although there has been quite a reduction since 2017-18, which we think has been due to public pressure on police. So, it is disappointing to see that the numbers are starting to increase again.

The Redfern Legal Centre and Slater and Gordon launched a strip search class action against NSW police back in 2022, and it’s being run on behalf of all people who had been strip searched by NSW police at NSW music festivals since 22 July 2016.

The civil suit is set to begin in May next year. So, how is the class action shaping up?

It’s shaping up very well. We are predicting it’s probably going to be one of the largest class actions against NSW police ever.

Anyone who has attended a music festival within the six years up to 2022, automatically are included in the class action. And if they don’t want to be included, they can opt-out at this stage.

What we want to achieve through the action is damages for those who have been subjected to a humiliating and invasive strip search by NSW police, but also, we want to emphasise that the law needs to change through this class action.

These unlawful strip searches will continue unless the law is more rigorous in explaining to police that a strip search cannot occur for minor drug possession.

And lastly, Sam, you’re the solicitor for police accountability at Redfern Legal Centre, and you’ve been monitoring police over the time of the decadelong campaign around NSW police use of drug dogs and strip searches.

The NSW Police Force appears to have been resistant to reforms around strip searches or even to show restraint around the use of procedures like move on orders over the past ten years.

Why does state law enforcement continue to resist ongoing calls for reforms in these areas your community legal centre has identified?

The main thing is that it looks tough on crime and tough on drugs and that is the narrative that keeps driving this unlawful behaviour.

I still think the NSW Police Force have a culture where they think they can just pay off unlawful behaviour, without looking at the systemic change that’s required in law and on the ground.

And until we change that culture and a culture within the NSW Police Force develops that values the trust between police and the community and it doesn’t encourage unlawful behaviour from the top down, then we will continue to see police powers bleeding out into areas that are unlawful.

It’s going to require a big cultural and legislative change within the police force. Unfortunately, I don’t think we are there yet.

But we will continue to put the pressure on NSW police to ensure that this culture does change over time.