The White Australia Policy Part 1: Constructing Fortress Australia

“This country shall remain forever the home of the descendants of those people who came here in peace in order to establish in the South Seas an outpost of the British race,” remarked Australian PM John Curtin, following the outbreak of hostilities with Japan during the Second World War.

The nation’s head of state for the majority of the global conflict, Curtin was appealing to long-running sentiment within the Anglo Australian community that sought to ensure the population of the country remained majority British descended. This was a policy reinforced in legislation.

Like so many politicians of the time – as well as a good number today – Curtin’s declaration whitewashes over the fact that on British arrival, this continent was the site of more than 500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations.

Indeed, this landmass has never been what might be described as a “white country”.

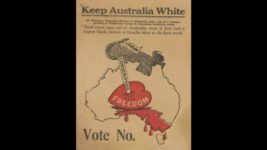

Enacted right after federation, the laws enforcing the strategy of keeping this nation majority British were collectively known as the White Australia Policy. And they were an extension of policies restricting Chinese immigration already in place in the colonies of NSW and Victoria.

These days, Australia is often hailed as a multicultural success story, and that’s rightly so on the ground. However, the legacy of the all-white policy looms large: it can be seen in the racial makeup of parliaments and the media.

And, of course, it’s there in our racist immigration and refugee policies.

Based on South African law

One of the first pieces of legislation passed by Australian parliament was the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (Cth) (the Act). And while not overtly stated within its provisions, the debates and lobbying that led to the Act, along with its application, reveal it’s Anglocentric focus.

Section 3 of the Act outlines who “prohibited immigrants” were. These included “any idiot or insane person”, someone suffering from “an infectious or dangerous disease” and sex workers. While its main clause sets out that a person who fails a dictation test, couldn’t gain entry into the country.

A migrant seeking entry into Australia had to pass a 50 word dictation test. Initially, immigration officers could choose any European language to run it in, while later down the track, any language would do.

This strategy allowed for anyone an officer deemed not worthy of entering could be barred.

The most well-known case involved Czech Jewish communist Egon Kisch, who after initial refusal, entered the country without permission in 1934. And as he was multilingual, Kisch was then forced to take a dictation test in Scottish Gaelic, which he failed.

The High Court of Australia went on to overturn the anti-Nazi campaigner’s illegal immigration status. Although, he was never seeking to remain here permanently.

The dictation test had the effect of non-whites not making the journey to Australia, and shipping countries refusing to issue tickets to those likely to fail. And by 1909, only 52 people had passed the test out of 1,359 administered, and from then on, no one ever passed it.

The Act also permitted the turfing out of noncitizen residents. Those convicted of a violent crime could be given a dictation test on release, and if they failed, they could then be deported. This applied to anyone not born in the country, except for British subjects.

Blackbirding

Passed one week before the Act, on 17 December 1901, the Pacific Islander Labourers Act (Cth), was another deplorable piece of legislation that enacted deportation laws, which the federal government felt necessary on founding the nation.

Over a 40 year period commencing in 1863, an estimated 62,500 South Sea Islanders were brought to Australia to work in the Queensland sugar cane, maritime and pastoral industries. This coercive practice – which at times involved kidnapping – was known as blackbirding.

As these people were paid a very low wage, they can’t be referred to as slaves, rather they were indentured labourers. But the treatment they were subjected to was akin to slavery. They were segregated, received corporeal punishment, and were often worked until they died.

Although, those of British descent weren’t happy with this system, as they asserted it threatened their jobs. So, after these migrants helped build the sugar industry, the newly-formed government passed federal laws, allowing for the deportation of the remaining 10,000 South Sea Islanders.

Fortress Australia

The last piece of legislation that comprises the White Australia Policy was the Post and Telegraph Act 1901 (Cth). It sets out how the post and telegraph services were to operate, under the oversight of the Postmaster General’s Department.

These laws have significance for the White Australia Policy as they governed the way that post from abroad would be entering the country.

Section 16 of the Post and Telegraph Act outlines that in terms of foreign mail, “no contract or arrangement for the carriage of mails shall be entered into on behalf of the Commonwealth unless it contains a condition that only white labour shall be employed in such carriage”.

This stipulation appears to seal the last loophole the federal government envisaged could have allowed “alien coloured” migrants to make their way onto Australian shores.

These laws, as well as the rest of the White Australia Policy, stood until the passing of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth). But it wasn’t until the Whitlam government passed the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) that the racist edifice is said to have been totally stamped out.

But the legacy of the White Australia Policy continues to flow through the provisions of the nation’s widely condemned migration and refugee policies of the present.