The Offence of Unlawful Assembly in New South Wales

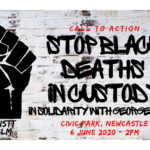

Tens of thousands of people took to Sydney streets over the weekend after Black Lives Matter protest organisers won a last minute battle in the New South Wales Court of Appeal.

The NSW Police Force and NSW Government had joined forces to block the anti-racism and anti-police brutality rally, ostensibly due to concerns over the spread of COVID-19.

But just moments before the rally was set to commence, the NSW Court of Appeal overturned the ban – declaring that the event did not amount to an ‘unlawful assembly’ under the law.

Similar protests were held around the country, but in other states, such as Queensland, Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk simply urged protesters to adhere to physical distancing, and did not take the decision to stop her constituents from expressing their political views through the fundamental democratic right to protest.

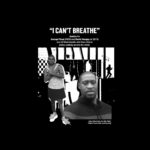

The impact of George Floyd’s death

Black Lives Matter protests were spawned in the wake of the death of George Floyd, who was asphyxiated as he was held down by police officers, in the US. His death sparked a global outcry, and although tragic, it has given Australians an opportunity too, to stand up for their own.

It has been more than 30 years since a Royal Commission into Indigenous Deaths in custody. And yet little has changed. Few of the recommendations from the Royal Commission’s final report have been implemented, and since then a further 432 indigenous people have died either in temporary police custody, or while serving prison time, and no officers have ever been charged over these deaths.

Racism in Australia’s police force and justice system

It is well documented that Indigenous Australians come up against racism at every turn in the Justice system, and there is a desperate need for change.

The death of George Floyd is very similar to the death of Dunghutti man David Dungay who died in a Sydney prison in 2015 after being physically restrained by officers, and after repeatedly exclaiming “I can’t breathe.”

Only last week, footage of a Policeman assaulting an Indigenous teen, using his food to sweep the young man to the ground before holding him down also surfaced.

Every day, indigenous Australians are treated very differently than white Australians by police, and it is exactly this – the prejudice they face, racial profiling and often a presumption of guilty over innocence that motivated tens of thousands of people to want to stand up for change.

Dwayne Kennedy who was imprisoned for two weeks during COVID-19 for sleeping on a park bench, due to a litany of errors within the court system. Mr Kennedy, who has a brain disorder as a result of brain injury, and suffers homelessness was only released after an appeal to the Victorian High Court.

A coroner is also currently investigating the death of Mr Kennedy’s sister, Veronica Nelson Walker, who was detained after she was arrested for shoplifting. While she was on remand, withdrawing from drugs, she died in the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre, Victoria’s maximum security women’s prison.

Western Australian woman, Ms Dhu, who was put into custody over unpaid fines, died of pneumonia and septicaemia. A coroner found that her life could have been saved, if she had been given better care.

Tanya Day, who died in hospital from a brain haemorrhage, which was caused after she fell and hit her head five times within the first hour of being placed in a police cell after being charged with public drunkenness, after she was found asleep on a train.

Sadly, there are hundreds of stories like these, although they don’t attract global attention.

The outcomes for Indigenous Australians who find themselves in trouble with the law are appalling. In fact, despite representing only 3% of the total population, more than 29% of Australia’s prison population are Aboriginal. In fact, since 2004, the number of Aboriginal people in custody has increased by 88% compared to a 28% increase for non-Aboriginal Australians.

One in four prisoners is Aboriginal.

And alternatives, such as circle sentencing and other preventative programmes have been hugely successful. Despite this, they have not been embraced in a mainstream way and often remain limited in their approach because of lack of government funding.

Demonstrators, not just those who took part in marches, but the many thousands who have shown solidarity on social media too, hope that their voices will now be heard, because for any real change to be effected, this issue needs to remain firmly in the spotlight, so that our politicians will begin to finally make meaningful changes that truly embrace the idea that black lives matter.

Unlawful assemblies in New South Wales

Knowingly joining or continuing in an unlawful assembly is a criminal offence under section 545C of the Crimes Act 1900 which carries a maximum penalty of 6 months in prison.

To establish the offence, the prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that:

- You knowingly joined or continued in a public assembly, and

- The assembly was unlawful.

The maximum penalty increases to 12 months in prison where you are armed with any weapon or loaded arms, or with anything which used as a weapon of offence is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm,

The law makes clear that assemblies include protests, demonstrations and processions, and these events are ‘public’ if they are conducted on a public road, public reserve or any other place which the public are entitled to use.

The section further makes clear that any assembly of five or more persons whose common object is by means of intimidation or injury to compel any person to do what the person is not legally bound to do or to abstain from doing what the person is legally entitled to do, is deemed to be an unlawful assembly.

When is an assembly lawful?

Part 4 of the Summary Offences Act 1988 (NSW) sets out a range of rules and requirements which must be complied with before a proposed assembly can be regarded as lawful.

Section 23(1) of the Act provides that an assembly is an authorised public assembly if:

(a) notice, in writing, of intention to hold the public assembly, addressed to the Commissioner, has been served on the Commissioner, and

(b) if a form of notice has been prescribed, the notice is in or to the effect of the prescribed form, and

(c) the notice contains the following particulars:

(i) the date on which it is proposed to hold the public assembly,

(ii) if the proposed public assembly is not a procession, a statement specifying the time and place at which it is intended that persons gather to participate in the proposed public assembly,

(iii) if the proposed public assembly is a procession, a statement specifying the time at which it is intended that the procession commence and the proposed route of the procession and, if it is intended that the procession should stop at places along that route for the purpose of enabling persons participating in the procession to be addressed or for any other purpose, a statement specifying those places,

(iv) the purpose for which the proposed public assembly is to be held,

(v) such other particulars as may be prescribed, and

(d) the notice specifies the number of persons who are expected to be participants in the proposed public assembly, and

(e) the notice:

(i) is signed by a person who indicates in the notice that he or she takes responsibility for organising and conducting the proposed public assembly, and

(ii) specifies the address of that person for the service on him or her of any notice for the purposes of this Part (which may include an address for the transmission of facsimiles or the sending of emails to the person), and

(f) the Commissioner has notified the organiser of the public assembly that the Commissioner does not oppose the holding of the public assembly or:

(i) if the notice was served on the Commissioner at least 7 days before the date specified in the notice as the date on which it is proposed to hold the public assembly—the holding of the public assembly is not prohibited by a Court under section 25 (1), or

(ii) if the notice was served on the Commissioner less than 7 days before that date—the holding of the public assembly is authorised by a Court under section 26.

Section 25 of the Act contains a mechanism for the Commissioner of Police to challenge a proposed assembly which complies with the above requirements.

The section provides that:

(1) The Commissioner may apply to a Court for an order prohibiting the holding of a public assembly in respect of which a notice referred to in section 23 (1) has been served if the notice was served 7 days or more before the date specified in the notice as the date on which it is proposed to hold the public assembly.

(2) The Commissioner shall not apply for an order under subsection (1) relating to a public assembly in respect of which a notice referred to in section 23 (1) has been served unless:

(a) the Commissioner has caused to be served on the organiser of the public assembly a notice, in writing, inviting the organiser to confer with respect to the public assembly with a member of the Police Force specified in the notice at a time and place so specified, or to make written representations to the Commissioner, with respect to the public assembly, within a time so specified, and

(b) if the organiser has, in writing, informed the Commissioner that he or she wishes so to confer, the Commissioner has made available to confer with the organiser at the time and place specified in the notice:

(i) the member of the Police Force specified in the notice, or

(ii) if that member of the Police Force is for any reason unavailable so to confer, another member of the Police Force, and

(c) the Commissioner has taken into consideration any matters put by the organiser at the conference and in any representations made by the organiser.

(3) A notice referred to in subsection (2) (a) may be served on the organiser:

(a) personally, or

(b) by registered post, facsimile transmission or email addressed to the organiser at an address, specified in the notice served on the Commissioner under section 23 (1) (e) (ii), as an address for the service of any notice for the purposes of this Part, or

(c) by leaving it with any person apparently of or above the age of 16 years at a postal address so specified.

And section 26 of the Act provides a mechanism for organisers to apply to the Supreme Court to authorise an assembly.

It provides that the organiser may apply to a Court for an order authorising the holding of the public assembly if:

(a) a notice referred to in section 23 (1) is served on the Commissioner less than 7 days before the date specified in the notice as the date on which it is proposed to hold the public assembly referred to in the notice, and

(b) the Commissioner has not notified the organiser of the public assembly that the Commissioner does not oppose the holding of the public assembly.

What about the constitution and the implied freedom of political communication?

Australia is one of the few developed countries not to have a national bill of rights.

In fact, only five rights are expressly guaranteed by the Australian Constitution:

- The right to vote (Section 41),

- Protection against acquisition of property on unjust terms (Section 51 (xxxi)),

- The right to a trial by jury for criminal cases in the higher courts (Section 80),

- Freedom of religion (Section 116), and

- Prohibition of discrimination on the basis of State of residency (Section 117).

There is no express right to free speech.

However, section 7 of the Constitution requires the Senate to be comprised of representatives who are “directly chosen by the people of the State”, while section 8 similarly requires that the House of Representatives “be composed of members directly chosen by the people.”

In the case of the Australian Capital Television v Commonwealth (1992) , the High Court relied on these provisions to find that the constitution enlivened a system of government whereby the people directly elect those who are in power.

This means members of parliament are representatives of the people, who are chosen by, and accountable, the public. This, the court found, essentially gives rise to a freedom of political communication.

The court found that the freedom empowers individuals to:

“communicate his or her views… criticize government decisions and actions, seek to bring about change, call for action where none has been taken and in this way influence the elected representatives…

The court added that:

“Absent such a freedom of communication, representative government would fail to achieve its purpose, namely, government by the people through their elected representatives.”

The freedom, the court found, is not restricted to communications between the public and government – it extends to political communications between individuals and groups within the community, and a range of methods of communication, including speech, written publications and actions on matters of political significance.

Limits to freedom of political communication

However, freedom of political communication is not completely unfettered – hate speech is an example of what many would consider to be beyond the limits of free speech, regardless of whether it is based in political views.

But not all encroachments are this clear cut, so what is the test for deciding whether or not certain communications can be banned?

The test is contained the case of Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1997), also known as the “Political Free Speech Case.” The judges in that case ruled that the curtailment of the freedom was allowed if the enacted law satisfied a legitimate purpose and fulfilled two conditions:

- It is compatible with the maintenance of the representative and responsible government mandated by the Constitution, and

- It is “reasonably appropriate and adapted” to the fulfilment of a legitimate purpose.

The judges in Lange found that “the freedom of communication which the Constitution protects is not absolute. It is limited to what is necessary for the effective operation of that system of representative and responsible government provided for by the Constitution.”

Freedom of political communication has been relied on to overturn parts of anti-protest laws in Tasmania, but whether a High Court challenge would lead to the repeal of anti-protest laws in New South Wales remains to be seen.