First Ever Conviction of an Australian Police Officer Over Aboriginal Death in Custody

A New South Wales police officer was found guilty over the death in custody of Dunghutti teenager Jai Kalani Wright on 28 November 2025, which was not only significant for his family, but the dangerous driving causing death conviction was further consequential, as it was the first time a NSW officer has been convicted over an Aboriginal death, in fact, it’s the first time any Australian police officer has been.

With the news of the outcome, social media feeds were awash with people expressing shock – shock that justice had finally been served, but also, shock that it has taken so long for it to be served.

An unmarked police car driven by sergeant Benedict Bryant crashed head-on into the stolen trail bike Wright was riding early morning on Gadigal land at an intersection in the Sydney inner city suburb of Eveleigh. The bike and another stolen car had been spotted close to the scene of the accident earlier on, and Wright was struck by an oncoming vehicle whilst he and others were being chased.

NSW District Court Judge Jane Culver agreed with the points made by Crown prosecutor Phillip Strickland SC, who put to the court that Bryant had received a direction not to pursue Jai on the trail bike, which an officer of his 22 year pedigree should have realised meant that the 16-year-old driver would likely not stop and would rather drive in a dangerous manner to avoid apprehension.

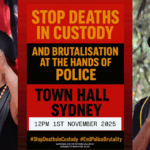

This conviction also comes on the back of a Stop Aboriginal Deaths in Custody campaign going back at least to the 1980s. This crisis involves disproportionate numbers of First Nations people caught in the criminal justice system and dying as a result. But the dampener in the current equation is Bryant hasn’t been sentenced yet, and it’s unsure his penalty will reflect the seriousness of his crime.

Guilty of causing death

“This verdict confirms that Benedict Bryant caused the death of Jai Wright. This is a tragedy that never should have happened,” said Nadine Miles, principal legal officer at the Aboriginal Legal Service NSW/ACT. “It is rare for police officers to face criminal charges when they are involved in the death of a community member and even rarer for a court to return a guilty verdict.”

“We are not aware of a previous instance where a police officer has been held criminally responsible for the death of an Aboriginal person in custody or in a police operation in NSW,” the senior lawyer continued. “It is critical that police are held accountable for their actions. The community should be able to trust that they will be safe when interacting with police.”

The inquest into the death of Jai Wright commenced in January 2024. But it was brought to an abrupt end a week into proceedings, when NSW state coroner Teresa O’Sullivan ended them and referred the case to the NSW Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) for the potential laying of charges against Bryant, which then took place on 19 February last year.

This development was an anomaly when looking back over the last decade or so. That is except for the time that O’Sullivan did the same in October 2020, in respect of a prison guard who shot an Aboriginal inmate in the back. This led to the likely first time an Australian prison guard had ever been charged in respect of such a death. However, the prison officer was eventually acquitted.

Bryant had pleaded not guilty to the one count of dangerous driving causing death, contrary to section 52A of the Crimes Act. In terms of the former sergeant, the Crown prosecutor had to show that he’d been driving in a dangerous manner, which lead to a crash and the death of the 16-year-old. The maximum penalty that Bryant is now facing is 10 years imprisonment.

The NSW DPP also laid a backup charge against the police officer’s name, which works as a second less serious charge that might serve as a conviction if the primary offence doesn’t stick.

This second offence comprised of one count of negligent driving occasioning death, contrary to subsection 117(1)(a) of the Road Transport Act (NSW). This traffic crime carries up to 18 months prison and/or a $3,300 fine, while if it is a second ‘major traffic offence’ within a five year period, then the penalties climb to 2 years inside and/or a $5,500 fine.

“Police use force against Aboriginal people at vastly disproportionate rates. There is a particular lack of accountability for police who cause harm to Aboriginal people,” Miles underscored. “The conviction of Benedict Bryant breaks with this trend and is an important step in the right direction,”

Dubious acquittals that spring to mind

Commentators tend to be careful about making pronouncements about firsts. But Sydney Criminal Lawyers has found over the last decade that it appears Bryant marks the first time a serving Australian police officer has ever been convicted over an Aboriginal custody death. This understanding has been garnered by speaking to First Nations experts, as well as consulting texts.

It is rare for a police officer to even be charged in respect of one of these deaths. It appears no prison officer has ever been convicted in this regard. It is even rarer for a corrections officer to be charged in respect of an Aboriginal death in custody.

Some custody death incidents spring to mind as cases that might have potentially countered this understanding, but on double checking, they confirm that Bryant’s conviction is the first.

These cases include that of John Pat, who was just a 16-year-old Yindjibarndi youth, when he died in a police cell on Ngarluma land in the Western Australian town of Roebourne on 28 September 1983, after he’d attempted to assist another Aboriginal man being beaten up by local police, only to then have officers turn on him, throw him in a police van, and subsequently drag him into the lockup to die an hour later.

The five police officers involved in the brawling were acquitted and even reinstated to duty in the wake of the trial.

The 19 November 2004 death in custody of 36-year-old Mulrunji or Mr Doomadgee, who belonged to the Bwgcolman community of Palm Island, and the subsequent acquittal of then Queensland police sergeant Chris Hurley is another key example of a law enforcement officer being exonerated, as this cop had brutalised his victim to the point of rupturing his spleen and liver.

QPS officer Hurley is not only notorious for not having lost his job over the killing Mulrunji but also for eventually receiving a promotion.

The starkest recent example of a police officer being acquitted of the killing of an Aboriginal person in custody was that of Northern Territory police constable Zachary Rolfe.

A sliding scale of charges were laid against Rolfe’s name in respect of the shooting death of 19-year-old Warlpiri Luritja man Kumanjayi Walker. This involved a charge of murder that was seconded by a charge of manslaughter, but if neither of them stuck, it was open for him to be convicted on violent act causing death. However, the all-non-Indigenous jury acquitted the officer of all three charges.

The outcome of the trialling of Rolfe stood as clear evidence of a criminal justice system that, until last week, was incapable of prosecuting a police officer in respect of killing a First Nations person.

After shooting Walker once in the back, Rolfe then directly shot two bullets into the boy’s ribcage as he was lying on his back on the floor with the officer’s partner on top of him, holding him down.

First signs of accountability

The Australian government’s real-time death in custody dashboard outlines that 617 Aboriginal deaths have occurred since the handing down of the final report of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in April 1991. This year alone has seen 33 First Nations people die in the custody of either corrections or police.

Coroner O’Sullivan announced a “profoundly distressing milestone” in mid-October this year, which comprised of the most Aboriginal deaths in custody in the state of NSW in one year, as 12 First Nations people had died in custody since the beginning of the year.

Legal experts and deaths in custody campaigners have hailed the recent outcome as a sign of finally reaching some police accountability in respect of First Nations deaths in custody.

However, Bryant remains unsentenced and there is the possibility for the courts to go light on him in sentencing. The other prospect for the outcome of the trial to be diminished is that the ex-officer is planning to appeal his conviction outright.

“From that first day we were told by a senior police officer that this happened, that a car pulled in front of Jai and caused the collision,” Lachlan Wright, Jai’s father, told the press after the handing down of the verdict, “after that, we had to put up with police investigating police, and this not being pursued by the DPP. We had to put up with going to a coronial inquest.”

“And if things can change in the future in regard to relationships between Aboriginal people in this country and the police force, maybe this won’t happen again,” the boy’s father added.