Five Years in Indonesian Immigration Limbo: An Interview With Hazara Refugee Karima Hakimi

Hazara woman Karima Hakimi, her husband, her four children and her elderly mother have all been stuck in the Indonesia immigration detention system on the island of Java since August 2017, with the succeeding years being lived in a state of limbo and devoid of basic human rights.

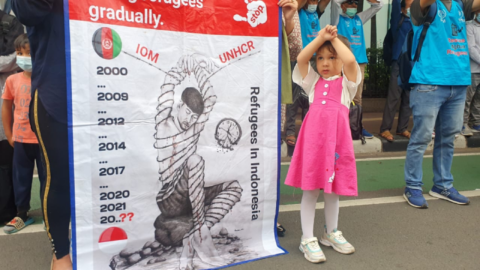

Despite having registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on their first day of arrival in Indonesia, and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) operating in the area, the Hakimis case for resettlement has not progressed in any substantial way.

The Hazara, who originate from Hazarajat in central Afghanistan, had been persecuted by successive Afghan governments for over a century. And under the five years of authoritarian Taliban rule that ended in 2001, their targeting escalated.

Human Rights Watch has this week reported that with the Taliban retaking control of the Central Asian nation last year, the Hazaras have now been the subject of repeated attacks coming from the Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP): the Islamic State’s affiliate in that country.

Fleeing the Taliban

Under the 2004 to 2021 governance of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, life improved for the Hazaras. The country’s third largest ethnic group was experiencing peace and prosperity for the first time after enduring decades of persecution.

However, in December 2014, now 34-year-old Karima was working as a midwife at the Rabat Clinic in the Doshi District of Baghlan Province, when three men arrived at her workplace with a pregnant woman in a bad condition. Unknown to Karima, these men were Taliban.

As the clinic was unequipped to assist the woman, Karima advised the group to go to the hospital. On their way, the armed men were picked up by police and arrested. And on release, they returned to the clinic blaming Karima for their capture and threatening her husband’s life.

The Hakimis then fled to the capital Kabul. But soon after arrival, Karima began receiving threatening phone calls. And fearing she may be kidnapped or killed by the Taliban, her family boarded a flight to New Delhi in July 2017, fleeing their homeland.

Thousands on our doorstep

Currently, there are about 13,700 refugees and asylum seekers stranded in Indonesia, waiting for resettlement in a third country. The Southeast Asian nation used to be a transit stop for those seeking asylum, but due to changes to Australian migration policy, they’re now stuck there.

As Fabia Claridge, spokesperson for refugee advocacy group People Just Like Us, explained in June, some of the stranded are there as a result of boat turnbacks, and further, our government has been paying the IOM to warehouse these people in the neighbouring country.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Hazara midwife Karima Hakimi about how her family came to be in the refugee camp where they’re currently living, the lack of progress her family’s case has received over the last five years, and her desire to be a positive part of a society.

Karima, you fled Afghanistan with your family back in 2017. You did so via plane to New Delhi, and then with the help of a people smuggler, you were able to fly to Malaysia and then on to Medan, Indonesia.

Since then, you and your six other family members have been living in refugee camps in Java. How did you come to be living there?

We arrived in Jakarta on 1st August, and we registered with UNHCR. I asked UNHCR for shelter, because we didn’t know anyone here and didn’t know where to go,

UNHCR told me they didn’t have shelter for refugees. They said you can go to the camp through the immigration office, not UNHCR.

My family arrived at the immigration office at 2 am and one immigration officer asked about us. I couldn’t speak Bahasa Indonesia, and the police couldn’t speak English. So, we used Google Translate.

He said, “Make me happy.” I was shocked and wrote, “How can I make you happy? What do you mean?” Later on, I understood he was asking for money, and he would give us room.

We only had $500. I gave him $200. He said that he would come back and take us to a place where other refugees were living. He never came back. I forget his name but remember his face.

We slept on the street in front of the immigration office for a week under the sun and rain. After a week on the street, they took us to a volleyball ground.

We spent five more days there. We had a tent, and it was very hot during the day and night. My kids got skin problems.

After that, they took us to Kalideres Immigration Centre. There were spaces for 170 to 180 people there, but we lived with 600 others. We lived there with some criminals

We had a 2 by 2 room with no window. We couldn’t see outside: whether it was day or night. I was pregnant.

We weren’t comfortable with Indonesian food. I ate biscuits with water one time for 24 hours. I had very low blood pressure, dizziness, and my legs had no power to walk. We were not allowed to have a phone or computer inside the immigration gaol.

There was no TV. My kids slept and cried all the time. We had a chance to go out on Fridays for only 2 hours. Around 400 people had only eight toilets and 2 hours out of 24 to take a bath and wash clothes.

I cannot explain how we felt and how the situation was for those four months.

Journalists twice came to Kalideres Immigration Detention Centre. And the UNHCR came once. They saw our situation, but nothing changed.

After four months of a hard situation, where we couldn’t even talk with our family and friends by phone, they took us to Jakarta Kota.

There each family had one room. We could go outside. We were allowed to have a phone and TV. But we still weren’t allowed to cook. We only had the food the IOM gave us.

In February 2018, we were interviewed by UNHCR, and after 2 months, we got our refugee cards. When my baby was born in May 2018, they took us to Ciputat Community House. We had a 3 by 3 room, with shared kitchen and washing facilities.

I lived in Ciputat for 4 years without any change in our resettlement process. I requested to change my place a lot, and because I was so stressed, I could not sleep at night.

Then, they took us to Serpong Dormitory. It’s been 7 months that we’ve been living here in Block A10-11, on the first floor.

We are living with different nationalities using a share kitchen, fridge, washing machine and a water dispenser in damp dark rooms.

We do not have the right to work or study. We do not have the right to buy a SIM card. We can’t have a bank account. Our kids can’t go to kindergarten or school.

Imagine how it is hard to live in limbo without any basic human rights in Indonesia under the support of UNHCR.

We have a monthly allowance of AUD $49 for kids and AUD $120 for adults.

We have to manage this money for food, water, electricity bills, clothes, shoes, basic healthcare in the clinics, for taxis to hospitals that the IOM introduced us to and our dental care, which IOM does not support.

We cannot go to nearby hospitals without the IOM agreeing. We do not have a normal life here. Nobody hears us.

I sent an email to UNHCR twice a week, explaining our problems. But I didn’t receive any response.

We feel stressed within all the cells of our bodies.

In fleeing to Indonesia, presumably you had Australia or another country in mind as your final destination. What has it been like trying to find a nation that’s willing to resettle you?

We had to leave Afghanistan and seek refuge in another country. All the world knows about the situation in Afghanistan, especially with the Hazara people.

We chose Indonesia with the intention of another country. But waiting for long years in Indonesia to go to a third country is really hard and exhausting. Especially since we refugees don’t have any basic rights here.

You’ve said that the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, as well as the International Organisation for Migration, have been problematic in their dealings.

What has this involved?

According to international immigration law, asylum seekers and refugees must be identified, accepted or rejected within 24 months. And they must have citizenship rights within 36 months.

Unfortunately, for some reason, the UNHCR has taken immigrants hostage for almost a decade or more. We believe that it’s against immigration law.

We demand justice and human rights.

We did not know that being a refugee in Indonesia would be the beginning of a bigger nightmare. That we would lose our golden time. We are dying every day.

The two big organizations, UNHCR and IOM, are supposed to be the defenders of refugees’ rights. But they’ve kept us here for years with no basic human rights. It is a form of modern slavey.

Refugees in Indonesia have been suffering unexplainable and pitiful situations. There is no freedom of movement, religious freedom, liberty, security, and there’s no access to basic human rights.

For instance, refugees do not have the right to buy a SIM card or have a bank account, even though, according to article 1 of the 1951 Geneva Convention and the 1967 protocol, refugees are eligible and have the right to resettlement.

But unfortunately, UNHCR Jakarta says that resettlement is not even in their hands but depends on resettlement countries.

If they don’t want refugees from Indonesia, UNHCR Jakarta cannot do anything for refugees.

I’m asking the world – the UNHCR and resettlement countries – if we refugees in Indonesia are all illiterate and living in limbo without any basic human rights, then who is responsible?

We are humans.

There are many Hazara refugees in Indonesia at present. Why do so many Hazara have to flee their homeland?

The Hazaras are one of the main ethnic and religious minority groups in Afghanistan, constituting around 20 percent of the population.

The Hazaras have long been subjected to discrimination and persecution due to our ethnic and religious identity.

The first Taliban rule in the 1990s was devastating for Hazaras— thousands were persecuted and massacred. Over the span of a few days in August 1998 alone, the Taliban killed over 2,000 Hazaras.

The last two decades of foreign intervention and experiments with a republican form of government were considered an era of opportunity for the Hazara community. This was one in which Hazaras were recognized, at least formally, as equal citizens under the 2004 Constitution.

After a long history of persecution and discrimination, the presence of the international community in Afghanistan, with their promise to support liberal democracy, inspired Hazaras to believe that this was a genuine opportunity for a better future.

Although the community was represented by prominent Hazara politicians, they did not necessarily give voice to the main concerns of ordinary Hazaras.

The community felt the continuation of systematic discrimination and a lack of meaningful political participation.

It was only at the grassroots level that the Hazaras played a central role in democratisation and institution-building processes, including by becoming major voices for liberal and democratic values within the media and civil society sectors.

Voter turnout in Hazara districts and provinces was consistently high. Hazara women had an active and visible presence in public spaces and spearheaded meaningful contributions to women-led initiatives.

I’m a trained midwife who speaks five languages. I was forced to flee my home country when some members of the Taliban wrongly thought I had reported them to police, which led them to threaten my life and my husband’s.

The Taliban were not in control of Afghanistan then. But since last year, they have retaken control.

So, what is the situation like in your homeland now?

The Taliban now has control of Afghanistan. Over the past 20 years, the Taliban were still active in remote areas, so it was hard and dangerous to travel in provinces and villages in Afghanistan.

The Taliban had influence in the villages, and they often planned suicide attacks and assassinations.

Over the past 20 years, they have assassinated and killed thousands of the military, civilians, and former government employees.

By wearing women’s clothes and changing their faces, even in the safest parts of Afghanistan, they can kill anyone and escape. Sometimes, if they were caught by the government, they would be released.

So, they’re now in control of Afghanistan, and the living conditions of the people – the military, civilians and especially women – are in serious danger.

If they want to kill or rape anyone, no one can stop them, especially Hazaras, as they’re the main targets for them.

And finally, Karima, you have applied for a sponsorship program in Canada. You also have Australia as a potential country to go to. What do you expect to happen from here?

I’ve spent five years in an Indonesian camp waiting for resettlement and there’s been no change in the resettlement process of my family from the UNHCR.

This situation is really hurting my mother’s health and I’m worried about my health in the future, on the other hand. The future of my children here without education really hurts me.

I am looking for a humanitarian program, with countries that receive refugees to get us out of this uncertain situation, to give us a new life and a chance to live a normal life.

My husband and I want to work and be a useful people in society. In this way, we can create a good future for our children so that they will be good and educated people in society and make the world better.

In Canada or Australia, if a group helps my family to resettle, we could start our new life according to the law of that country.

I really hope that people help us get out of this limbo. It is really hard to explain about living in limbo without any basic human rights.