“Legalise and License the Supply of Drugs”: An Interview With Chris Daw QC

Criminal defence barrister Chris Daw QC is an outspoken advocate of drug legalisation.

The 1912 International Opium Convention was the first transnational drug control treaty. Born out of concerns over opium use in China, the document was signed in the Hague, and placed restrictions around the manufacture and distribution of substances derived from the opium and coca plants.

Under pressure from the United States, the League of Nations established the 1925 Geneva Convention on Opium and Other Drugs. It established stricter international drug controls. And as a last minute addition, cannabis was added to the list of targeted plants.

The Geneva Convention and a number of other subsequent drug treaties were consolidated in the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which is the key document of modern prohibition. It’s accompanied by the 1971 UN Convention on Psychotropics and 1988’s UN Trafficking Convention.

When this extensive legal framework was being established, the idea – at least initially – was to improve the wellbeing of people who were using drugs. However, by the time Nixon launched the war on drugs in 1971, it was more about those in power broadening their reach.

Time to admit failure

In June 2011, the Global Commission on Drug Policy declared the war on drugs a failure. Comprised of former heads of state, ex-UN officials and leading intellectuals, the commission explained that instead of curtailing supply, the war has escalated drug availability and consumption.

The commission report also asserts that the drug war has created a huge criminal black market and focused scarce law enforcement resources on it, as well as causing mass incarceration, increasing the harms related to these substances and marginalising people who use them.

Indeed, the NSW Crime Commission Annual Report 2015-16 outlines that in this state the illicit drug trade continues to be the main source of income for organised crime. And while law enforcement efforts are resulting in larger drug seizures, this has no real impact on their availability.

It’s now readily acknowledged by a growing number of professionals that drug prohibition is a grand mistake. The 2017 Australia 21 report involved a number of former police commissioners and ex-heads of corrective services calling for an end to the war on drugs.

Of rising legal concern

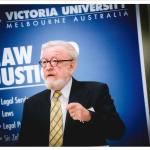

Chris Daw QC is a prominent UK criminal barrister. He’s been defending people in courts and dealing with the laws that prohibit drugs for the last 26 years. And he recently published an opinion piece in the Spectator titled As a QC, I Believe the Time Has Come to Legalise Drugs.

Mr Daw makes clear that one thing he’s learnt over his time in criminal justice is that “people want to take drugs and nothing will stop them”. And there’s “nothing more baffling” to him “than the continuing attempt to use laws to prevent people” from taking illicit substances.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Chris Daw QC about the harms that are created solely by the criminalisation of drugs, the impact that prohibition is having on the criminal justice system in the UK and how he understands a legalised and regulated drug market would operate.

Firstly, you’re a barrister, who specialises in serious crime. What sort of cases or scenarios have you been involved in professionally that have led you to the conclusion that prohibited drugs should be legalised?

I began my career, like most criminal defence lawyers, dealing with low level, petty crimes, such as shoplifting, burglary, small scale dealing and assault.

As I progressed, I began to deal with the highest levels of the UK drug trade. In one case, I acted for the alleged head of an organised crime group, responsible for importing over AUS $1 billion of pure cocaine from South America into Europe.

I have defended in cases of gun running, blackmail, witness intimidation and even murder, all linked to the drug trade.

A major justification for prohibiting drugs, which remains the prominent one, is that they cause harms. However, many drug law reformists assert that the harms caused by drug laws are much greater than those caused by the substances themselves.

What’s your take on the debate around harms related to drug prohibition versus those caused by the drugs themselves?

There is no doubt that most mind-altering drugs, including the legal ones – caffeine, alcohol, tobacco – can cause serious physical and psychological harm to users. Some are extremely addictive and lead to dependency, sometimes after only a small number of doses.

However, most of the serious harms arising from the use of drugs are caused by the law and not by the drug.

The most important factor here is the need to commit constant crime in order to fund an addiction, which can run into thousands of dollars a week, which few addicts can fund from legitimate earnings.

Drugs like heroin and cocaine are expensive purely because they are prohibited. The drugs themselves are cheap to produce at source.

That inflated cost is what leads to the crime committed by users, and the more serious crimes of the drug gangs themselves, due to the very large profits on offer in the prohibited market.

All of that would largely disappear if drugs were legalised and supplied to users at a sensible cost.

There is also a major issue with the uncertain quality and purity of illegal drugs, whereby dangerous chemicals and even poisons are added to drugs – to bulk out the weight – sometimes with fatal consequences for users.

What impact is drug prohibition having upon the criminal justice system in the UK? And what sort of changes would drug legalisation have upon it?

In my view, drug prohibition is the single greatest driving force behind the great majority of criminal activity, at every level, and is the reason that UK prisons are full to overflowing in 2019.

Legalising drug supply would allow vast resources to be diverted from drug law enforcement to deal with other criminal activity, which concerns the public, and would, crucially, allow massive investment in health and rehabilitation services for drug users.

In your recent article, you mentioned that many people enter the prison system without having touched drugs prior. But, due to the availability of drugs in correctional facilities, it’s often the first place some try them.

What would you say the availability of illegal drugs in prisons tells us about the system of prohibition?

The drug market is the same as any other market – it is about supply and demand. Those in prison often have a drug habit when they go in and they will do almost anything to obtain continued supply.

Others try drugs in prison, because it is easy to do and they are often in a vulnerable state, when first sentenced.

The additional security issues mean that drugs are even more expensive in prison than on the outside, which in turn creates an opportunity for large profits for those prepared to risk smuggling them in, including prison staff.

This shows that there is no way to stop drug use, when demand is so high, even in the most secure buildings in the country.

So, it is better to look at ways to cut out the criminal gangs and allow users safe access to drugs, alongside treatment services, whether they are in prison or not.

Recreational cannabis is now legal in 11 US states and the entire nations of Canada and Uruguay.

In Australia, there are growing calls in the community for cannabis legislation. And at present, in the Australian Capital Territory, there’s a bill before parliament that could see personal possession and use legalised in that jurisdiction.

What’s happening in regard to cannabis legalisation in the UK? And given worldwide trends, why is the UK in its current position?

There is no serious move towards the legalisation of cannabis in the UK, largely due to our distraction by Brexit and other political issues, which have dominated the entire political landscape in recent years.

There is widespread public support for some form of decriminalisation of cannabis, but there is insufficient political pressure on government for this to be taken seriously, until the Brexit impasse has been broken.

Drugs are not a priority for the UK government at the present time.

Calls for drug decriminalisation and legalisation are getting stronger in Australia. These days, there are former police commissioners, ex-Directors of Public Prosecution, and former Supreme Court judges all calling for drug law reform. Although, for the most part, politicians are silent.

What’s the state of the drug law reform debate in the UK?

There are many serious commentators, including senior police officers, calling for radical drug law reform, such as limited forms of decriminalisation.

Equally, there are loud voices, in politics and the media, calling for tougher approaches to drug dealing and drug-related crime.

There is no consensus in the public debate, but, undoubtedly, some of the most prominent experts on drug policy now believe that prohibition has failed and is, in fact, a major contributor to the evils associated with drug use and supply.

And lastly, many in the community find it hard to imagine a society, where drugs that are outlawed now are legal. This is despite drug prohibition only having been around for about a century.

In your understanding, what does a post-prohibition society look like? And how would a regulated drug market operate?

I would favour legal and licensed drug supply – for almost all prohibited drugs – through a national network of licensed dispensaries, in which drugs would be provided after an assessment of the user’s health, and alongside the availability of high-quality state funded treatment programmes.

I am undecided on whether dispensaries should be operated on a commercial model – for profit – or should be entirely state-owned.

Whichever model were chosen, the price of drugs would be controlled entirely by the state, set at levels that were low enough to eliminate a shadow illegal market and most forms of acquisitive crime, currently committed to fund a drug habit.

In some cases, it would make sense to dispense drugs for free, particularly for long term addicts of heroin, as a first step towards treatment and addiction therapy.

They key for me is to stop talking about chemical substances as if they are inherently amoral – whether to use or supply – and instead treat the drug problem as a health and crime issue.

What is the best way to improve the health of users and reduce the amount of crime, committed in and around the drug trade?

For me, after 26 years as a criminal lawyer, the answer is obvious – legalise and license the supply of drugs. Even if it does mean that I might one day be out of a job as a result.