Uncle Ray Jackson on Aboriginal “Murders by Neglect” in Custody

The Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody handed down its 339 recommendations on 15 August 1991. It considered 99 First Nations custodial deaths that occurred between 1 January 1980 and 30 May 1989.

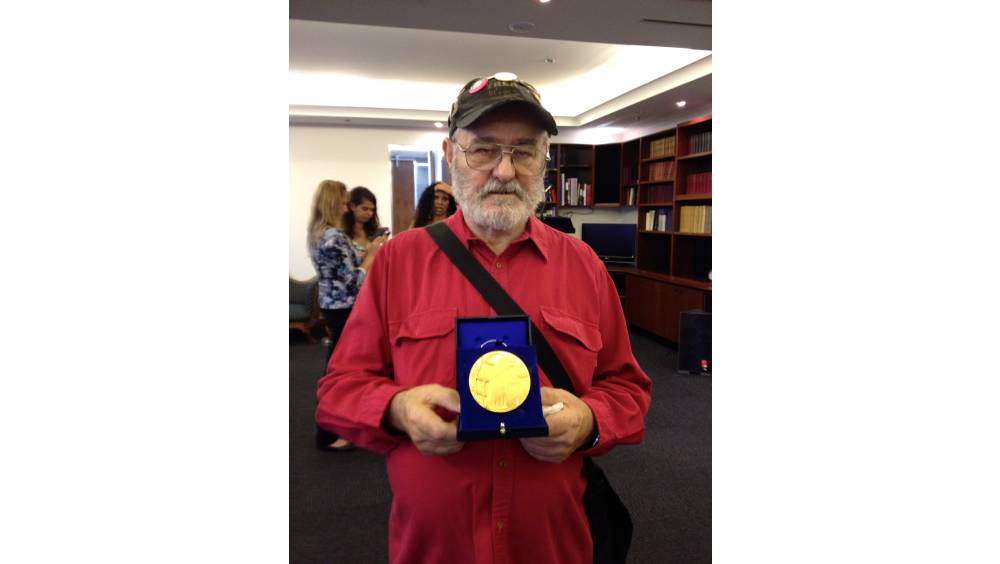

“The Royal Commissioners looked at that and, in their wisdom, did not find any custodial officer, corrections or health officer, guilty of anything whatsoever,” said the late Uncle Ray Jackson in a speech he gave in August 1996.

“Now I could stand here and go through at least a dozen cases that, we argue, were absolute murders and nothing less.”

At the time he gave the speech, Jackson was the coordinator of the Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Watch Committee. And the Wiradjuri elder later went on to establish the Indigenous Social Justice Association (ISJA) of which he was president.

In terms of the remaining 99 deaths considered by the national inquiry, Uncle Ray told the crowd that another two dozen needed to be further investigated due to “suspicious circumstances”, while the remainder could be put down to “suicide or natural causes”.

“We prefer to call them murder by neglect,” the renowned Aboriginal rights advocate made clear, “because that is exactly what it is.”

A law unto themselves

Talking in the early days of the Howard government, Jackson turned his attention to consideration of police. He maintained that law enforcement is problematic the world over due to its culture, which allows officers to break the law with impunity at the same time as they’re supposed to uphold it.

As an example, he cited the “six drunk off duty cops who kicked John Pat to death in front of 23 witnesses and got off”. A Yindjibarndi youth, Pat was just 16, when he was killed in the WA town of Roebourne in 1983. The officers involved were still employed as Jackson was delivering his speech.

In terms of watching Australian police break the law and get off scot-free, Jackson said, “It gives our people a total hatred of that system – a total hatred built up over many years, hundreds of years, in fact.”

Systemic prejudice

May 1989 was the cut-off date for the custodial deaths the Royal Commission considered. As of August 1996, Jackson informed the Action for World Development crowd he was addressing, that there had since been a further 105 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people die in custody.

“We thought, at long last we will get the 339 recommendations and we will put them in place, and the deaths will stop happening,” Uncle Ray continued. “Here we are, just over five years later, and we don’t have a decrease.”

According to Jackson, over the half decade since the handing down of the inquiry’s final report, both the arrest and incarceration rates of First Nations peoples had doubled, while the number of custodial deaths over the last seven years had outstripped those considered by the commissioners.

And quite disturbingly, Uncle Ray’s sentiment still holds true 25 years on.

Right now, just a little over a month out from the 30th anniversary of the Royal Commission’s final report, there have been over 440 more First Nations deaths in custody since April 1991, while Indigenous people now account for 29 percent of the nation’s adult prisoner population.

Demands that stand

Uncle Ray then set out that the watch committee had put in a submission to the then NSW Department of Corrective Services calling for four reforms. The first was that the committee should have access to custodial staff in order to educate them on the Royal Commission recommendations.

The second was a call for the establishment of an Aboriginal team to investigate First Nations custodial deaths. The third reform was that when a coroner finds an officer has breached duty of care in relation to an Indigenous custodial death, that they then be answerable to the courts.

The final demand was that First Nations communities are able to remove their people from the “white custodial system”. Jackson said they should to be taken out of prison and placed in “healing centres”. And he added that they need to be put back in touch with “land, which is their culture”.

A death sentence

“We have a 19-year-old kid who was picked up,” Jackson said. “He smashed a car window and took something out.” On being arrested, the First Nations youth couldn’t afford the $300 bail that was set. So, “they shipped him out to Parklea on Friday night and on the Sunday, he was dead”.

Uncle Ray underscored that the youth died inside because the magistrate didn’t consider Royal Commission recommendation 92, which stipulates incarceration should be a last resort. And nor did police consider recommendation 87 that advises arrest should only be taken as a final measure.

The long-term rights activist explained that when the Aboriginal youth went into prison, he entered an “alien environment”. One in which he had to watch over his shoulder every minute out of fear of being bashed, raped, “fitted up” or to ensure that prison guards weren’t “playing mind games”.

“I wonder why people kill themselves,” Uncle Ray concluded. “It’s murder and I can’t put too fine a point to it.”