Australian Government Establishes “Enduring Form” of Offshore Detention on Nauru

Home affairs minister Karen Andrews and Nauruan president Lionel Rouwen Aingimea released a joint statement last Friday, outlining that Australia and the South Pacific island nation have signed a memorandum of understanding “to establish an enduring regional processing capability in Nauru”.

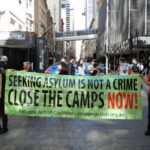

This decision to create an “enduring form of offshore processing” is unexpected as the eight-year-long mandatory detention regime is an internationally condemned human rights disaster that hasn’t achieved any of its stated aims.

The numbers in offshore detention peaked around the beginning of 2014, with 4,183 people having passed through either Nauru or the now closed Manus Island facility since August 2012.

But right now, only 107 asylum seekers remain in Nauru, and 124 are located in Papua New Guinea. And the annual cost of continuing to hold these people offshore is $3.4 million each.

Andrews said the decision to continue with an offshore detention capability in Nauru is all about “stamping out the threat of maritime people smuggling”. And she reiterated the party line that “there is zero chance of settlement in Australia for anyone who arrives illegally by boat”.

The upcoming federal election has been cited as a reason to make this public display of willingness to further torture and deprive the planet’s most desperate people on the soil of a poorer nation.

However, it may be closer to the truth that the abandonment of Afghanistan is prompting the move.

A brief history of offshore processing

The Nauru immigration detention facility was closed in 2019. Today, the 100-odd refugees and asylum seekers that remain on the tiny island live in refugee camps. This is similar to PNG, where the Manus Island facility was closed in 2017, with the remaining detainees now in Port Moresby.

The Nauru Regional Processing Centre was first established by the Howard government in 2001, as part of its Pacific Solution. By 2005, only 32 asylum seekers remained in the centre, and the incoming Rudd government closed the facility and ended offshore detention in December 2007.

But the Gillard government recommenced offshore processing in August 2012. And despite the policy constantly being spruiked as a means to save lives, the UNSW Kaldor Centre has pointed out that Gillard actually stated the reintroduction was a “compromise” made “to get things done”.

Under Gillard’s system, 1,055 asylum seekers who arrived by boat were transferred to Nauru and Manus to undergo processing and serve a period in detention that was meant to equate to the time taken to gain refugee status through the official channels.

Most of this first cohort was transferred back to Australia following newly incumbent PM Kevin Rudd’s announcing the policy of mandatory offshore detention on 19 July 2013. This new program left asylum seekers with no prospect of resettlement in this country regardless of status.

Three thousand, one hundred and twenty five people who travelled here seeking asylum were then transferred to either Nauru or Manus. And once the Abbott government took office in September that same year, Operation Sovereign Borders was instated with its aim of pushing back the boats.

A failed policy

In the Cruel, Costly and Ineffective report, UNSW academics Madeline Gleeson and Natasha Yacoub set out that despite Australian politicians continuing to assert the necessity of offshore detention as a deterrence to others, no new asylum seekers have been sent to these centres since 2014.

The pair explain that since that time the militarised Australian Border Force has been intercepting asylum seekers at sea and returning them to their places of departure, often “going to extraordinary lengths” to do so, despite the option of offshore detention being available.

The report sets out that over 2015 to 2019, 23 boats had been turned away.

And another myth the academics dispel is that the people being sent to offshore detention never make it to Australia. The report states that of the 3,125 people condemned to indefinite offshore detention, 1,161 are currently in Australia living in the community, albeit in uncertain circumstances.

“Thus, despite having formally pursued offshore processing since August 2012, Australia transferred asylum seekers to Nauru and PNG for less than two years,” the academics wrote in August this year.

“It has then spent the past seven years in a prolonged and costly policy bind, trying to find humanitarian solutions outside Australia for all those subject to the policy who cannot be returned to their countries of origin.”

The greater cost

Over 2012 to 2017, the offshore detention program cost taxpayers over $5 billion. And it continues to churn through over $800 million a year. But the real cost has been to the lives and minds of the people who fled persecution seeking a better life.

Leaked in mid-2016, the Nauru Files outlined that assaults, sexual abuse, self-harm and child abuse were rampant at the island detention facility. And of the 2,116 reports detailed in the files, 51 percent of them involved kids being detained by our government.

In 2018, the Kids off Nauru campaign was run, which successfully saw the remaining 80 children on the island brought to Australia. But this was not before many kids in their early teens attempted suicide and 30 of them developed a rare psychological disorder, which left them close to comatose.

But the harms continue to occur for those who remain in offshore detention eight years on. A 36-year-old Tamil detainee was run down by a car whilst riding a motorcycle on Nauru in February. This attempted murder saw the locals in the car reverse back over his body after they hit him.

Indeed, fourteen people have lost their lives in Australian offshore detention, or as our government would put it, fourteen “illegal maritime arrivals” have died.

Zero chance

On 22 January 1954, Australian signed the 1951 Refugee Convention. This document makes it legal for people fleeing persecution from their countries of origin to seek asylum in signatory nations. It also provides that no government forcibly return people to countries where they face persecution.

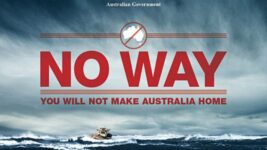

In the early days of Operation Sovereign Borders, our PM Scott Morrison was the immigration minister overseeing the program. When asylum seekers were sent to Nauru or Manus Island, they were shown video footage of Morrison greeting them.

“If you have a valid claim, you will not be resettled in Australia,” our current prime minister told those who’d risked their lives to get here. “If you choose not to go home, then you will spend a very, very long time here.”

While today, if you go to the government’s official Operation Sovereign Borders website, there’s a recently posted video of home affairs minister Andrews stating, “The Australian government is responding to the security situation in Afghanistan.”

The minister then proceeds to explain that Australia’s migration policies have not changed in the wake of what is happening in the country we just pulled out of after 20 years of war. She added, “No one who arrives by boat will ever settle here.”

So, it seems highly likely the announcement that Nauru is still on the cards is all about deterring people fleeing for their lives from Afghanistan attempting to come to Australia.

“Do not attempt an illegal journey by boat to Australia,” Andrews tells those who are in such a dire situation they might do so.

“You have zero chance of success.”