End Prohibition. Vote HEMP: An Interview With Dr Andrew Katelaris and Michael Balderstone

As Australian historian Dr John Jiggens recalled in 2010, an article appeared in a major Australian newspaper in 1938, warning about a “Mexican drug” that causes madness. And this report introduced the term “marijuana” to the Australian public.

“Under the influence of the newer drug, the addict becomes at times almost an uncontrollable sex-maniac,” the article read. Seven weeks later, another report appeared in the paper outlining that marijuana cigarettes had been smoked at a party in Sydney.

This sensationalised reporting sparked local concerns about the marijuana plant, which was quite ironic, as, at the time, Australians regularly used dozens of cannabis-based medicines that were readily available via prescription or over-the-counter at the local chemist.

Australians weren’t big tokers back in 1930s. It wasn’t until 1964, when a large infestation of wild cannabis was found growing along the Hunter River between Singleton and Maitland in rural NSW that pot smoking started to take off.

Feeling somewhat left out of the party, in 1976, Australian authorities began paramilitary raids of hippy colonies that enjoyed the herb in Queensland’s Cedar Bay and around Nimbin in NSW. And so began the decades-long war upon a relatively innocuous plant.

Just not cricket

The United States led the world into drug prohibition. Although, today, within its own borders, there are now 10 states where the recreational use of cannabis has been legalised. And in 33 US states, medicinal cannabis is not only legal, but accessible to patients.

Not to be upstaged, Justin Trudeau declared in 2015 that his entire nation would be legalising the plant if he was elected as Canadian prime minister. And it worked, as of October last year, cannabis is legal and available retail throughout the country.

These global developments got former Australian PM Malcolm Turnbull thinking. He announced that he was going to legalise medicinal cannabis, turn it over to Big Pharma, eradicate botanical products and make sure most patients couldn’t access it. And in February 2016, he passed a bill to ensure this.

The politics of cannabis

Established in 1993, the Help End Marijuana Prohibition – or HEMP – Party advocates for the legalisation of cannabis, which is a move that an ever-increasingly large percentage of the community would like to see. And this month, HEMP is running 14 candidates in the federal election.

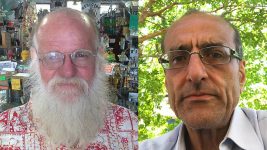

On the ticket for the Senate in NSW, we have two of the nation’s cannabis heavy weights: Dr Andrew Katelaris and Michael Balderstone. The doctor knocked the criminal justice system for six last year, when he proved that it was necessary for him to provide patients with unsanctioned cannabis oil.

While Mr Balderstone is the bedrock of cannabis activism in this country. He’s both the HEMP Party president and the head of the Nimbin HEMP Embassy. The easiest way to vote both of them into the Senate is to find the cannabis leaf on the ballot paper and write number 1 underneath it.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to Dr Katelaris and Mr Balderstone about the cannabis climate at present, the reasons why the plant has been tarnished and the form that they advocate cannabis legalisation should take in this country.

Firstly, both of you have been advocating for cannabis law reform for decades now. And over recent years, you’ve seen attitudes and laws regarding cannabis and hemp shift significantly around the globe.

How would you describe the stage we’re now at in this country in the move towards cannabis legalisation?

Mr Balderstone: I can tell you, living in Nimbin, it’s never been more difficult for a cannabis user. People have stopped driving.

Later in May, we’re going to lose our licence automatically for three months if we register with cannabis. We know you can register days after use. And we’ve got permanent police hunting us all the time.

It’s never been more difficult. And there’s a lot of frustration around.

Dr Katelaris: I have to echo a lot of the negative sentiments that Michael said.

There’s a lot of progress around the world. And some years ago, we were hoping to be the focus. Now, we’re seeing that here things aren’t getting better. In fact, they’re getting worse.

The medical roll out is a shambles. It’s really just a redistribution from the poorest people to the pharmaceutical giants. It’s a disaster what’s happening in this country.

So, if elected into the Senate, what are your plans? How would you go about changing the laws around cannabis?

Mr Balderstone: I would be canvassing everybody. I still find it hard to believe that anyone you sit down and talk reasonably with thinks that cannabis should be illegal.

So, there’s a lot of powerful, vested interests holding us at bay.

Dr Katelaris: Part of our strategy is to use the ancient common law right of the jury to nullify statute law that they find oppressive.

Following our victory of November last year, on the medical necessity, we’re now taking to the Court of Appeal the right for a jury to be fully informed of their power to give a verdict against the facts if they find a law oppressive.

And we feel that this, if it’s properly exploited, will be like a nail in the coffin for prohibition. It won’t be voluntary. It will be by force.

So, in your understanding, when did cannabis officially become outlawed in this country?

Mr Balderstone: I don’t think they really enacted it until the hippies started smoking it and finding it wild along the Hunter River back in the 60s.

Dr Katelaris: The rumblings of the prohibition started in the 30s. I’ve seen newspaper articles where they talk about the government being warned about this new menace. So, we were caught up in the reefer madness.

The real prohibition: the actual busting people was in the 60s, because cannabis use was tied in with political activism and rebellion.

And what would you say has been the cost of cannabis prohibition in Australia?

Mr Balderstone: The social cost has been the broken families. The people in gaol. The people whose lives have been tipped upside down.

For a plant that’s never killed anyone in 10,000 years, prohibition has killed a lot of people. And it has damaged a lot of people’s lives. The social cost is massive.

Dr Katelaris: It’s not only the social cost. There’s the industrial cost.

In the documentary Billion Dollar Crop, it clearly outlines that the prohibition of cannabis as a drug was a smokescreen for the destruction of industrial hemp at a time when nylon and other synthetics were launching into the market.

Besides the social cost, these other costs are great. Can you image if Henry Ford could have got the hemp plastic car up in 1941? Panel beaters, insurers, road fatalities: all these things would be dramatically minimalised.

And the ecological disaster we’re now having, probably wouldn’t have happened if we stayed with hemp as an industrial crop. The cost is beyond calculation.

Mr Balderstone: It is. And it’s a unique long, strong fibre. We could have had hemp growing instead of cotton. All those rivers would have been OK. And we could be eating hemp seed instead of fish oil. These are two tiny examples.

It’s potential for helping save the Earth and climate change is massive.

So, the reefer madness and all of that propaganda was part of a push to wipe out the hemp industry in order for industries that are environmentally destructive to move forward?

Dr Katelaris: I don’t think that’s a matter of dispute anymore. The US Marijuana Tax Act was enacted in 1937. At that stage, they couldn’t just ban things, because the people could still think for themselves. They would ask, “Why are you banning something that we’ve been using for medicine?”

So, they enacted a tax regime where you had to pay such a high tax on any transaction of cannabis or hemp in any form. It was a backyard way of prohibiting it. But, the connection between that and the nylon industry is very well established.

Mr Balderstone: Prohibition of cannabis came about as the petrochemical and pharmaceutical industries were just getting going. It’s beyond a coincidence.

What sort of role would you say cannabis played in the community prior to prohibition?

Dr Katelaris: Australia, at various times, was proposed as a hemp colony, because of the importance of nautical hemp. It was required for the navy of Empire.

When the American War of Independence succeeded the British lost their source of hemp. And they had a problem with Russian hemp.

So, they were looking to plant it somewhere else and that was going to be Australia. But, it didn’t turn out that way for a number of reasons.

And why is it so important that this plant becomes legal once more?

Mr Balderstone: Environmentally, it’s huge. It’s obvious for the environment, as in cleaning up dirty soil. It can take out the toxins, as in replacing cotton, etc.

But, also, the war on drugs has just gotten out of control. What might have started off as a little scam to try and control pain relief and the profits to be made, has turned into a global nightmare.

They’re building the biggest gaol in Australia, just down the road in Grafton. It’s all privatised. And they always remind me of the big hotels. You’ve got to keep them full or they’re not economical.

So, we’ve just got ourselves caught up in such a mess, because of what is really a war on the best pain relief product on the planet.

Dr Katelaris: The Americans have a patent on the neuroprotective effect of CBD going back 30 years. At the same time, that they were spending billions of dollars in prosecuting people, they were aware that it could reduce neurotrauma and functional loss.

We’re dealing with people of no moral stature whatsoever. We are dealing with very evil people. This isn’t an issue of policy. It’s an issue of common sense versus darkness.

Mr Balderstone, the annual Nimbin MardiGrass is about to take place this weekend. What can those who attend expect?

Mr Balderstone: We’ll get a big crowd this year. Police doing saliva testing and blocking the road last year stopped a lot of people coming. But, we’re finding our way around that with a lot of designated drivers.

And we’ve got Ubud, our local transport service to help people. The drug testing has been such a below the belt hit to cannabis users. It’s got a lot of people angry about it.

So, I’m looking forward to it. We’ve got people from California, Canada and Amsterdam here to talk about how it is in countries where it’s legal. And hopefully, that will inspire a few people. It’ll be good.

Dr Katelaris, it’s now been five months since your historic win in court. You were found not guilty on some very serious supply and manufacture charges, after you argued a defence of medical necessity.

What do you think about the significance of your win these days?

Dr Katelaris: It was only really the first step, because with the narrow way the law interprets the defence of medical necessity, it’s not open for the majority of people who use cannabis for medical purposes.

But, it opened the whole idea of the jury being informed of its right to give a verdict on conscience in a District Court. We want to inject some conscience into this whole process, which is otherwise lacking at all levels of government.

I’ll just echo what Michael said about the expansion of the prison population. When I was sitting in Cessnock gaol watching 24/7 construction work duplicating the prison, it was a very challenging thing.

And lastly, there’s a bill before ACT parliament that allows for the legal possession of up to 50 grams of cannabis. It looks set to pass, but it won’t establish a legal supply chain. The NSW Greens are going to push for the establishment of a regulated market in this state.

What form of cannabis legalisation is HEMP advocating for?

Mr Balderstone: We think it was a mistake ever making it illegal. And we’ve got to find our way back there. But, as a first step, people should be allowed to grow a few plants themselves.

My personal preference would be to use the massive experience so many Australians have with growing and breeding cannabis, instead of giving it to giant corporations, which is what’s happening.

There are hundreds of thousands maybe – at least 80,000 – jobs out there waiting to happen if we could create a cottage industry.

I would licence growers to supply top quality medicine. It would be enough to make a living. You would work it out on the amount supplied. So, you’d get a licence to supply 50 or 100 kilos.

Dr Katelaris: To give a bit more structure to those suggestions. What we should aim for is a three-tier level of supply.

The first tier, which Michael already mentioned, would be homegrown. But, not some miserly one or two plants. It should be something like 20 or 50 plants per person. The only restriction is you can’t sell it. If you are going to grow it, you can’t sell it.

The whole idea of restricting cannabis was based on an illusion that it was somehow dangerous. And if people grew more of it, they’d just abuse it, and we’d just end up with a bunch of stoned zombies, which is nonsense. That doesn’t happen.

The next tier is proxy growing, where people with a passion or a scientific interest can take on patients. Say you were interested in multiple sclerosis or a child with epilepsy, you might take on three or four thousand patients that want to use the product you generate for them.

You do your own research. And because you are selling it to people, it has to be subject to tests for purity and potency. But, nothing more. Nothing more than food regulation.

At the last tier of supply, you could have your pharmaceutical cannabis that costs three times more. And the bloody doctors can sit there comfortably prescribing it, but their waiting rooms are going to be very empty.