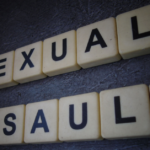

“Strip Searches Are Effectively a Form of State-Sanctioned Sexual Assault”.

Deputy state coroner Harriet Grahame released her report on the inquest into the deaths of six patrons at NSW music festivals last Friday. And it contains a recommendation that the NSW Police Force scale back its use of strip searches at such events.

Right now, police use of strip searches is out of control. Teenagers who attend festivals have to factor in the very real prospect that two armed officers might take them into a tent and ask them to remove their clothes.

This is not limited to festivals either, it’s also happening on the street and around train stations right across the state. At Sydney’s Central Station, police now have special screens, where they can order a commuter to strip off on their way home from work.

And it’s only getting worse. NSW Greens MLC David Shoebridge released figures last December, revealing that police had increased its use of strip searches by 47 percent over the four years to June last year. Indeed, over 2017-18, police made 5,483 people take their clothes off in front of them.

The deputy coroner asserts that strip searches should only be used in circumstances of drug supply, and not for suspected personal possession, which is how they’re applied most of the time now. She also recommends that reasons for a search be recorded on video prior to conducting it.

A law unto themselves

“This is a powerful recommendation, backed up by credible evidence tendered before the coroner,” Mr Shoebridge said. “This is the first time we’ve seen a coroner identify how damaging and unproductive strip searches are, especially when it comes to dealing with the personal use of drugs.”

“There’s no doubt that the bulk of NSW police who are forcing people to undergo strip searches don’t understand the law, and are regularly breaching it,” he further told Sydney Criminal Lawyers. “This is remarkable considering what a negative impact strip searches can have.”

A stark example of how officers are unaware of their powers – or are flagrantly disregarding them – came to light last Friday, as it was reported that a 22-year-old woman was stopped by two male officers out the front of a St Marys pawn shop and ordered to lift up her shirt and undo her bra.

Teleaha Bower told Nine News that she wasn’t doing anything out of the ordinary at the time the officers approached her. And she was left in tears following her ordeal that was conducted in full view of a male employee working inside the shop.

“Strip searches are effectively a form of state-sanctioned sexual assault,” Shoebridge continued. “And the thought that NSW police don’t understand the basic laws that constrain their exercise of this power is deeply distressing.”

Misunderstood or disregarded

The police powers to strip search civilians are set out in the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), also known as the LEPRA. And it makes clear that what Ms Bower alleges happened to her is against the law.

Officers can only search a person in the field if they have a reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing, and “the seriousness and urgency of the circumstances” warrant it. This means police operate on the assumption that small amounts of drugs are a matter of such gravity that it justifies this invasive practice.

The legislation further outlines that strip searches cannot be carried out by officers of the opposite sex to the subject, they must not be conducted in view of a person of the opposite sex, and they must be conducted in a private area, not out the front of a hock shop.

Section 33 of the LEPRA states that when police are strip searching children between the ages of 10 and 18, a parent, guardian, or someone else who can represent their interests must be present. And thankfully, police do not have the power to strip search children under the age of 10.

But, NSW police is also applying rules that aren’t set out in the LEPRA. Seemingly in response to the campaign against strip search overuse, it just released its Personal Search Manual, which states officers can direct search subjects to squat, lift their testicles or breasts, and “part buttock cheeks”.

Strip searching girls

Released last week, data obtained via freedom of information laws by the Redfern Legal Centre (RLC) sets out that over the last three years, police officers have strip searched 122 girls under the age of 18. And during that same timeframe, 3,919 women have been forced to strip off in front of officers.

The RLC recently commissioned a UNSW report into strip search use that found there’s been a twentyfold increase in their use since 2006. And the report calls for an overhaul of the laws, so the circumstances when strip searches can be performed is precisely defined.

The figures released last week also revealed that since 2016, officers of the law have strip searched two 12-year-old girls, as well as eight 13-year-olds, which has led members of the community to ask what sort of circumstances could warrant strip searching primary school aged children.

“It’s hard to imagine the set of circumstances that would make that reasonable,” Mr Shoebridge said. “Officers don’t understand the rights that the children have. They’re simply undertaking strip searches like they’re a routine part of police practice, but they’re not.”

Trauma inducing/retraumatising

And in a theatre of the absurd moment, NSW police minister David Elliott appeared at a “let’s justify strip searches” press conference, and told reporters that he’s “got young children” and if he “thought the police felt they were at risk of doing something wrong”, he’d “want them strip searched”.

Mr Shoebridge was clear that the minister’s comments show “how ignorant he is of the impact of strip searches, and how damaging they can be to young people”. And he underscored that this is especially so for youths that have been the victims of sexual assault.

RMIT’s Dr Peta Malins explained in May that people who had been subjected to a strip search can experience trauma as a result. And for those who have been sexually assaulted in the past, a strip search can cause them to reexperience the incident.

“A strip search can be an extremely destructive trigger exercise,” Mr Shoebridge concluded. “NSW needs not only new laws, but we also need a new police minister.”