The Inherent Racism of Australian Police: An Interview With Policing Academic Amanda Porter

The Aboriginal Deaths in Custody movement has been reignited. Last weekend saw tens of thousands of people gather in capital cities and regional centres to protest the systemic violence in Australian policing and criminal justice systems that targets First Nations people.

The catalyst for these mobilisations was the obscene footage of African American man George Floyd being killed by some Minneapolis police officers, and the subsequent uprisings that have swept across the United States as a result.

The four officers that killed Floyd did so as if it was simply part of their duty. One officer knelt on the man’s neck for eight minutes in front of members of the public: officer Chauvin gazed up occasionally, seemingly unfazed by their cries to stop. Another officer tried to shoo onlookers away.

And following the incident, the point has been repeatedly made that this act of deadly police brutality was produced by US policing systems that were founded upon racial prejudice and violence towards people of colour.

The colonial legacy

The same can be said about law enforcement institutions in this country. Just take the latest national custody statistics. These reveal that in March, 29 percent of the adult prisoner population was made up of First Nations people, while they only account for less than 3 percent of the overall populace.

Indeed, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are the most incarcerated people on Earth.

Then there’s First Nations deaths in custody, which are ticking over so fast that the tally being kept at The Guardian set out on 1 June that there had been 432 such deaths since 1991, however by 7 June, the updated count put the figure at 437 Aboriginal custody deaths.

And there has never been a single conviction of a police officer or prison guard in relation to any First Nations custody deaths going all the way back to the beginning of the Australian colonial project.

That’s not to mention overpolicing. The mother of a teenager, who’d been subjected to police violence, put it succinctly last week when she said that her family is subjected to “extra obligations to answer to people” on the street regarding what they’re up to simply because they’re Aboriginal.

Serving the public

The teenager was a 16-year-old boy who was thrown face down on the ground by a NSW police officer in a Surry Hills park on 1 June. The officer felt emboldened to do this, despite the fact that at that moment police violence towards people of colour was being condemned across the globe.

The constable kicked the youth’s legs out from under him, whilst pinning his arms behind his back. The officer did this in response to some bad language that came his way during a back and forth verbal exchange that he’d been a party to.

Just some tricks of the trade from an employee of an institution well-founded in racial prejudice.

Melbourne Law School senior fellow Amanda Porter has a focus on policing. Sydney Criminal Lawyers spoke to the Brinja Yuin descendant about the racial prejudice in both the Australian and US policing systems, which were both born out of the British colonial project.

Since the 25 May killing of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, the point has been made that institutions like the state police in the US were built upon racial prejudice against African American people.

Therefore, incidents of racial violence are likely to be perpetrated by these entities. Amanda, in your understanding, what does it mean for US police forces to have been established with a racial bias?

To say that US state police were founded on racist violence is simply to acknowledge the historical facts in the development of these forces. This is a pattern which continues into the present. And many books have been written on this topic.

As is the case here in Australia, the centralised police departments began to form in the early 19th century, beginning in Boston, New York City, Chicago and elsewhere.

But, in the southern states, some of the earliest policing models included slave patrols, which date back to the early 1700s. Slave patrols were responsible for controlling and punishing runaway slaves.

Historian Sally Hadden describes in her book Slave Patrols that in 1837, Charleston in South Carolina had a slave patrol with over one hundred officers, which was far larger than any northern city police force at the time.

Even after the slave patrols were formally dissolved following the Civil War, law enforcement agencies continued to police Black Code laws and Jim Crow laws until 1968.

That’s not to mention the complicity of the police—and the judicial system more generally—in turning a blind eye to lynchings and failing to intervene and punish perpetrators when African Americans were being murdered by mobs.

Law enforcement agencies oversaw the removal of citizens of the Cherokee, Muscogee, Chocktaw and other First Nations, as part of the Trail of Tears.

There are many other examples of racist violence.

So, how does this racism in the US system play out today?

Considering these historical foundations, it’s understandable that on seeing the footage of the fatal shootings of Ahmaud Arbery, Jordan Davis and countless others by civilians, many refer to these as contemporary lynchings.

And given the experiences of bereaved families in seeking accountability for these killings, even more so.

That’s not to mention the countless fatalities, police brutality and violence suffered by black, brown and Native Americans at the hands of US police.

Many will remember the Los Angeles demonstrations that broke out after the 1992 acquittal of police officers for the beating of Rodney King. In Ferguson, there were the 2014 demonstrations following a long list of fatal shootings.

Trayvon Martin was shot by police in 2012. Mike Brown was in 2014. Tamir Rice was also shot in 2014 and then there was the death by asphyxiation of Eric Garner at the hands of the NYPD that same year. There was also the death in custody of Sandra Bland in 2015.

There are more complete lists here and here. But, these lists don’t include missing and murdered Indigenous women and children in Turtle Island, cold cases and near misses, which are whole other stories.

These lists also don’t include racial profiling in other instances, such as police disproportionately targeting black, brown and Indigenous Americans for “driving while black”, stop and search and so on.

So, what about the idea of the police being here to help the people?

Society likes to tell itself stories about the police. Most people are familiar with the story of the father of the modern UK police Robert Peel and his friendly bobbies.

Peel himself stated, “The police are the public and the public are the police.” But, this is a myth, in my point of view.

There’s the idea of police forces being fundamentally democratic institutions, established to serve the public, to protect and promote public safety, and to uphold and enforce the law for the people.

This is a narrative that’s reinforced and continues to dominate narratives about policing both historically and in the present.

You’ve also researched policing in the UK and have found links to the Transatlantic slave trade.

Over the thirty years before the establishment of the Metropolitan police in London, a private police force known as the Thames River Police was established at Wapping on the banks of the River Thames.

Though often neglected in policing history, the Thames River Police was a significant forerunner to Sir Robert Peel’s modern police.

The Thames River Police were funded almost entirely by the West India Committee: a political lobbying collective consisting of plantation owners with proprietorial interests in the sugar and slave industries in the Caribbean.

Moreover, unlike the Peelian bobbies and their concern for public safety, the Thames River Police were founded on a preventive logic.

In other words, by investing 1,000 pounds in the employment of a private security force, the West India merchants and planters would see a significant minimisation in cargo losses from opportunistic theft: estimated at 500,000 pounds.

In spite of these links between the early police and the slave industries, it’s remarkable how seldom imperialism and settler colonialism feature in academic commentary on policing.

Despite the seemingly overt links between the slave trade and the development of the modern police, surprisingly – or perhaps not so surprising – very few scholars seem interested in researching or reflecting on this fact.

Indeed, police have had more to do with empire building, imperialism and capitalism, than safety – and this has always been the case.

Many Australians decried the police killing in Minneapolis, but overlooked the prejudice in the local system.

Although, the Stop All Black Deaths in Custody protests that took place nationwide last Saturday went a long way to setting them straight.

Australian police forces were established early on during the colonial project, while First Nations people were being dispossessed and killed.

Can we say that Australian police forces were built upon racial prejudice against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in a similar manner to what happened in the United States?

Yes. Everyone was quick to call out racism in America, but were either ignorant or blind to history and current experience on our own doorstep.

Australian police forces were similarly founded on violence: racist violence, imperial violence and settler colonial violence. That’s fair to say for a number of reasons.

Firstly, some of the earliest form of state policing were established with the specific purpose of extending the colonial frontier, finding escaped convicts, fighting the Aboriginal resistance and overseeing massacres.

The early police weren’t modelled on Robert Peel’s friendly bobbies: the communitarian style of policing, which developed in Scotland Yard.

In colonial Australia, the early police were modelled on the Royal Ulster Constabulary: the paramilitary police model, which oversaw the 19th century oppression of Ireland.

The NSW Police Force was established in 1862. What were some of its forerunners? And how did they operate?

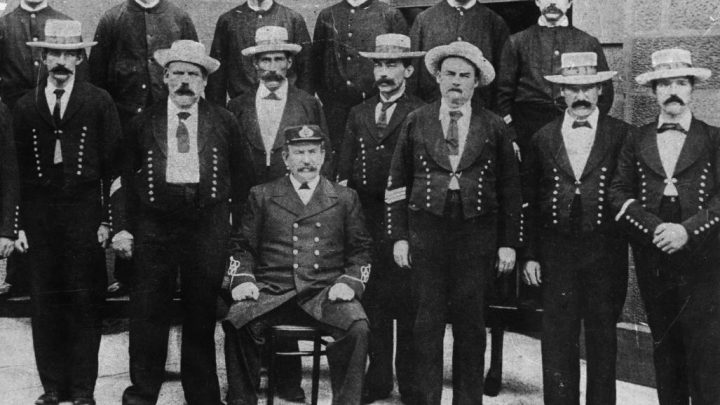

In the colony of NSW, the key institutions included the Border Police, the Mounted Police and the Native Police. All three organisations were known for their extreme violence and savage acts of brutality.

Historian Henry Reynolds describes the Mounted Police as “the most violent organisation in Australian history”.

The Mounted Police were assisted by the Native Police: a coercive body designed to control and dispense with dissident Aboriginal people.

The Native Police were established by British colonialist Alexander Maconochie in 1837. They used European firearms and horses with Aboriginal trackers, who helped orientate the troops.

Maconochie had observed the Sepoys—a paramilitary force in India which was funded by the East India company—and adapted the idea to the Australian colonial context.

The activities of the Native Police were not supported by legislation. But, nevertheless, operated until the 20th century.

So, as you’ve set out, Australian police forces have always had an antagonistic and often violent way of dealing with First Nations people. How would you say this plays out today?

It comes back to the issues raised above in terms of the violence of policing, and how the history of the police – whether in the US, the UK or Australia – is inextricably linked with histories of colonialism, imperialism, racist violence and capitalism.

You see this violence play out in overt and covert ways. Whether it’s the 1989 police fatal shooting of David Gundy: an innocent, unarmed Aboriginal man shot in his Marrickville home during an illegal police raid.

Then there’s private security firm GSL allowing Ngaanyatjarra elder Mr Ward to “cook to death” in the back of a prison van in the Western Australian outback in 2008.

There are countless other examples and zero accountability. There’s just a woeful and entirely inadequate police complaints system.

This issue has been addressed more eloquently by writers such as Latoya Rule, Celeste Liddle, Amy McQuire, Alison Whittaker, Chelsea Bond, Melissa Lukashenko, Allan Clarke, and Larissa Behrendt, among many others.

But, the inherent racism in Australian policing systems is not just limited to fatalities.

No, it’s not. In addition to fatal shootings and deaths in custody, Aboriginal people are routinely discriminated against in other ways.

There are many examples of CCTV footage displaying the misuse of police powers and illegal police activity circulating right now on this website and others.

I gather you saw the latest footage that came to light last week, involving a 16-year-old Aboriginal boy who was thrown face first onto the ground by a police constable in Surry Hills?

Yes. In relation to this new video, NSW police commissioner Mick Fuller said last week that the police officer in question was just having “a bad day”.

This response is fairly reflective of the leadership of police commissioners in response to police complaints. I know this as I used to work as a volunteer at the Redfern Community Legal Centre.

It goes without saying that this is against the values and principles embodied in recommendation 226 of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. It recommends that complaints about police should be investigated by a body totally independent of them.

Sometimes I wonder if Mick Fuller, or any of the other commissioners, have even read the recommendations.