Is It Illegal to Refuse a Strip Search in NSW?

In case you’ve been living under a rock over the last 12 months, the use of strip searches by New South Wales police has skyrocketed in recent years. NSW Greens MLC David Shoebridge released figures last December showing that the use of this invasive procedure rose by 47 percent over the four year period ending in June 2018.

A campaign against their overuse was initiated as a result, which emphasises that strip searches are only to be used as a last resort, not as routine police practice. Indeed, the law stipulates that in the field, strip searches can only be conducted when the “seriousness and urgency” of the circumstances make the procedure necessary.

The laws applying to strip searches are contained in the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), commonly known as the LEPRA. And they provide that an officer must hold a reasonable suspicion about certain matters in order to strip search them.

Reasonable suspicion is not defined in the legislation. The leading case on the meaning of reasonable suspicion in the context of warrantless searches is 2001’s Rondo versus R, which provides that a reasonable suspicion “involves less than a reasonable belief but more than a possibility”, and must have “some factual basis”.

But, even though the rules for strip searches are contained in the LEPRA, many are unsure about what constitutes the reasonable grounds of a suspicion, whether an individual can refuse a search, and what police are permitted to do if a person refuses.

Well, is it illegal?

“It is not illegal for someone to refuse an unlawful strip search,” explains Redfern Legal Centre head of police accountability practice Samantha Lee. “However, the cards are stacked against the person who does not comply with a police request of this nature.”

“On its own, the indication by a sniffer dog is not enough to establish reasonable grounds to conduct a strip search”, she told Sydney Criminal Lawyers, “and a person would be within their rights to refuse a strip search on this basis.”

However, Ms Lee warns that if a person refuses a strip search, officers “may use force against them”. And this “could result in the situation escalating and the person resisting being charged with hindering police”.

The offence of hindering police

Section 546C of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) contains the offence of resisting or hindering police. The section provides that “[a]ny person who resists or hinders or incites any person to assault, resist or hinder a police officer in the execution of his or her duty shall be liable on conviction before the Local Court to imprisonment for 12 months or to a fine of 10 penalty units, or both.” A penalty unit is currently $110 in our state, which means a maximum fine of $1,100 applies to the offence.

This is the offence police charged Goulburn man Luke Moore with back in April 2017, when he refused a strip search. So, while there is no specific offence of refusing a strip search, police may rely on section 546C to arrest and charge a person who refuses a search.

However, it is important to note that if transpires that the search was unlawful, the charge is may be thrown out of court, which is what occurred on appeal in Mr Moore’s case.

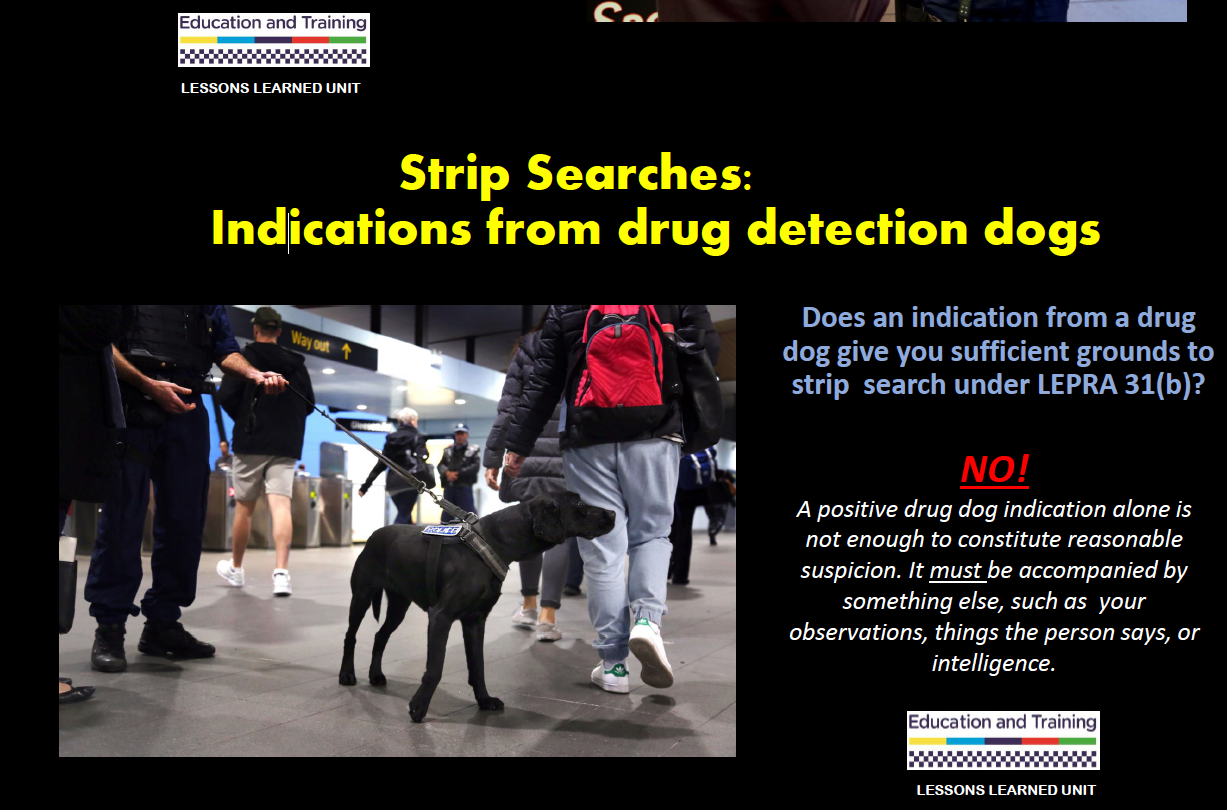

A positive indication by a sniffer dog is not enough to conduct a search

“I am strongly of the view that a positive indication by a drug detection dog is not sufficient to raise the suspicion on reasonable grounds required for a personal search,” Sydney Criminal Lawyers principal Ugur Nedim states. And he’s referring to both regular and strip searches.

Mr Nedim observes that while the LEPRA states that police can use drug dogs to assist in “general drug detection”, there’s nothing in the Act that says officers can carry out a search on the basis of a sniffer dog indication, and nor is there anything that states that it can constitute reasonable suspicion.

The criminal defence lawyer goes on to point out that the 2006 NSW Ombudsman report on drug detection dogs found that illicit substances were only located on 26 percent of searches that followed a positive indication.

And as part of the anti-drug dog campaign Sniff Off, Mr Shoebridge has been collecting the data relating to searches carried out after a dog indicates. And he’s found that since 2009, searches prompted by a dog turned up no illicit substances two-thirds to three-quarters of the time.

Mr Nedim points to the findings of former NSW Supreme Court Justice Rex Smart in the leading case of Rondo, when he stated that in order “to form a reasonable suspicion, there must be ‘more than a possibility’” that a person is in possession of illegal drugs, and that such a low percentage of findings following a positive indication cannot meet that test.

He adds that “any search based upon that indication alone would be unlawful”, and that “there needs to be something more to suggest illicit drug possession at the particular time” to ground a lawful search.

He explains that any drugs or other illegal items found pursuant to a search based on a positive indication alone would be subject to the exclusionary provisions of section 138 of the Evidence Act. The section provides that a court must exclude evidence derived from an unlawful search if the desirability of admitting the evidence found (eg evidence of drugs) is outweighed by the undesirability of admitting evidence found in that way (ie through an unlawful search).

This means cases can be thrown out of court where illegal items such as prohibited drugs are found during unlawful searches.

Nedim’s view is supported by the findings of the Ombudsman’s report, which concluded that:

“Given the low rate of detecting drug offences following a drug detection dog indication, it is our view, supported by Senior Counsel’s advice, that it is not sufficient for a police officer to form a reasonable suspicion that a person is in possession or control of a prohibited drug solely on this basis”.

But as Mr Shoebridge points out, despite all of this, the incidence of police carrying out strip searches following a positive indication by a drug dog basically doubled over the years 2016 and 2017. And 64 percent of those searches turned up no illicit substances whatsoever.

Should I consent to a strip search?

Another important aspect to be aware of when being searched by a police officer is to never provide consent. If you do agree to a strip search, then anything that follows is legal, regardless of whether officers acted in accordance with search protocols.

Should I resist being stripped searched?

Even if an individual understands that the basis for the police searching them is unwarranted, it’s best to follow an officer’s directions anyway. As Ms Lee states, the odds are against a person if they don’t comply.

“The recently released and updated NSW Police Personal Search Manual directs police officers to use force if a person fails to comply with a strip search,” Ms Lee says. This means that as an officer is likely to believe what they’re doing is lawful, they’ll use force if resisted.

The NSW Police Force is basing this direction on section 230 of the LEPRA, that allows an officer who’s performing a function contained within the legislation “to use such force as is reasonably necessary to exercise the function”.

However, Ms Lee doubts that this is actually legal. “As far as I’m concerned, any use of force by police when conducting a strip search is unlawful because the law clearly states a strip search is a visual inspection only,” she explains.

A recently released UNSW report found that since 2006, strip search use by NSW police has increased twentyfold. The study was commissioned by the Redfern Legal Centre, as part of its Safe and Sound campaign, which aims to see strip search laws and procedures changed.

And are these searches warranted?

Luke Moore is currently in the process of suing NSW police over being strip searched. Last week, he related that he’d refused to be strip searched in the back of a paddy wagon, as he didn’t believe the lack of urgency around the circumstances made it necessary.

And a subsequent strip search at the local police station turned up nothing. Moore was then charged with hindering police. He was initially convicted of the offence by a magistrate, but a District Court judge later overturned this, as it was found the reasoning of officers didn’t warrant the search.

According to Moore, police should never be strip searching citizens in the field for illicit drugs. “Any amount of drugs that’s small enough to be hidden in your underwear is not serious or urgent enough to warrant the extreme violation of a strip search,” he put forth.